The Pedestrian review - a short, summery 2D platformer that turns signs into playgrounds

Side-stroller.

When we move around cities we are navigating several varieties of space simultaneously: on the one hand, the tangible contours of buildings and roads, and on the other, the abstract routes, dynamics and barriers imposed by the city's maps and signs. The tension between these kinds of space can be sinister: maps and signs, after all, exist in part to deny you full access to the city's geography, to enforce laws and property rights. They keep secrets from you. But they can also be a source of delight, an invitation to read your surroundings as several realities jostling against one another, never quite rubbing along harmoniously. After 10 years of living in London, I still get a quiet thrill from walking between Underground stations, re-ravelling connections I understand only as coloured lines on a map.

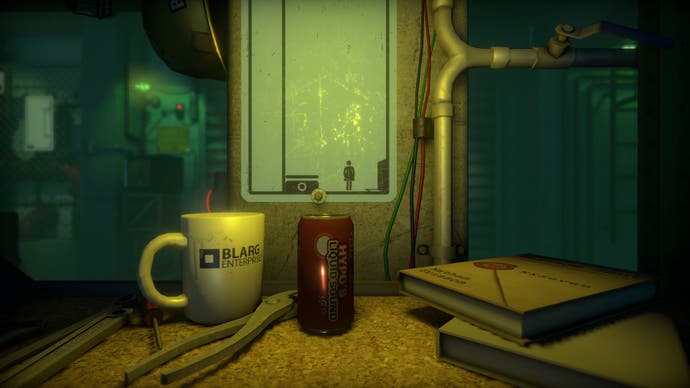

Skookum Arts' The Pedestrian leans into this delight. It literalises the idea that signs fabricate their own kinds of space within/atop urban geography by turning those signs into rearrangeable chunks of platform level, completion of which transports you deeper into a sleepy 3D metropolis. You play a 2D human doodle familiar from a billion toilet doors, drawn to life on a whiteboard. Proceeding to the right, you find yourself sliding between surfaces in a cluttered office, the camera tracking you gracefully as though following a butterfly, a blissful jazz score tickling your eardrums.

Doors and ladders in each sign allow movement to another, but these entrances and exits aren't all connected to begin with. You'll need to link them by hitting a button to enter plan view, moving signs around with the cursor (providing they aren't locked inside a frame) and dragging lines between them, as long as they're not obscured by another sign. You can enter plan view at any point to fiddle some more, but the catch is that once you've moved between signs, that connection can't be broken without resetting the puzzle. You need to join things up in the correct order before making your move.

Within this conceit, there are some elementary but nicely executed platforming gambits to reckon with. You'll search for door keys, throw switches to raise elevators, and haul checkbox crates around so you can jump to ledges. Puzzles are often grouped around hubs, where you venture into peripheral signs to gather objects you need to progress in the middle. Some signs are dangerous - there are spinning sawblades, and laser beams you'll need to either block or deactivate - but this is an extremely laidback game, with no lives, timers or combat elements and thus, infinite time to savour the light, shadow and picturesque detritus of the urban backdrop. It helps that there are so few actual people around - you'll spy vehicles, but I only recall encountering one 3D human being. There are more damning conclusions to draw, perhaps, about the act of stripping a city of citizens in order to play games with signs, but I didn't find the emptiness eerie: it made me feel like I'd wandered into town during a siesta.

Later puzzles meddle with the core principles a bit. You'll find vials of yellow paint that allow you to lock a sign so that it doesn't reset - useful when you need a switch to stay switched when you re-link signs, for example. Sometimes you're able to invade a screen (the game's pause menus are pleasingly tucked into CRTVs that dot pavements and shelves, as though left out for the recyclers). Most intriguing are the puzzles that blur the gap between the clean, mechanical world of the signs and their surroundings. Often, you'll have to wire together electrical sockets within signs, so that a current can flow through to activate something in 3D space, like a hydraulic bolt that's stopping you moving another sign. You'll take frequent trips in metro trains, tapping buttons inside dashboard displays to travel to new locations as afternoon wears on into nightfall.

There are a few puzzles that may require trial and error, but The Pedestrian (which shouldn't last you longer than an evening) is far more intuitive than it is complex. Partly this is due to the lucid visual design: the key props are neatly distinguished, and there are post-it notes stuck to walls so that you know what kind of puzzle you're dealing with. You can feel your way along some of the threads without quite knowing what you're doing, which leads to that difficult-to-design-for crescendo where realisation coincides exactly with resolution. The best conundrums are those where, having slowly introduced you to an idea, the game nudges you into doing something unexpected with it: a key, for example, is good for more than unlocking a door.

All that said, it does feel like there should be another layer to the game, though there's a twist in the last 20 minutes that plays into a concluding scene reminiscent of The Witness. But then, The Pedestrian isn't entirely about puzzles: it's about how beating them unlocks a tightly regulated world, and the peculiar intimacy this conjures between the game's entwined realities. Like a Situationist embarking on a very lazy dérive, the camera cuts through urban strata for every set of signs you weave together, diving into and out of the background as your character navigates a world that is all surface. For all the near-complete absence of fully fleshed-out human beings, there's a lovely emphasis on turning up traces of human activity - knotted shoes tossed over telegraph wires, stickers on lampposts, a wobbling Hula dancer in a window. Little pieces of life, nestled amongst signs that have ceased to be signs and become rather like treasure.