The story of the Atari Jaguar saviour that never came out

"We made it all up as we went along."

The year is 1994 and it's a typically bright morning in Sunnyvale, California. Chris Hudak is riding the Caltrain to work, powerbook in his lap, dozing in and out of consciousness. Arriving into the office sometime around noon, he rocks up at his cubicle and is approached by team leader and head designer BJ West. BJ has decided, in his capacity as captain, that his motley crew really need a staff meeting. Furthermore, he determines it would greatly improve morale if that meeting were to be held at the Brass Rail, a nearby strip joint. In the words of Hudak, they "all nod and gravely agree".

Dave, the DJ at the Brass Rail, is no stranger to these 'meetings' and celebrates their entrance by playing a load of industrial metal, much to the dismay of the girl dancing on the stage. The team share a pitcher of beer and muse on how this beats the hell out of spending the day at Atari's offices. Everyone agrees and the meeting is concluded. Begrudgingly returning to work, the team cap off the working day with a plastic dart gun fight, conducted with weapons procured from the local Toys 'R' Us. Another typical day in the life of the Black ICE\White Noise team, a group of rookie designers charged with the near-impossible task of saving the Atari Jaguar from destroying America's most legendary video game developer.

The mid-90s were perhaps the most transformative period in video game history. The leap from 2D to 3D and the amount of experimentation that took place at the time still staggers me. It's not just the power of those once-new machines I find incredible, but the sheer amount of choice we had back then. Today, we have the PlayStation 4 and Xbox One, two (relatively) similar systems, then there's Nintendo with its quirky little handheld, and the goliath that is the PC. But between 1993 and 1996, there were more failed major console releases than there were consoles released in the last decade. Nevermind the fact there were still multiple PC alternatives for the mouse and keyboard community, such as the Mac or the Amiga, or indeed Atari's own line of computers.

In late 1994, one of those many machines was Atari's ill-fated Jaguar. Destined to fail and become joke-fodder for mid-2000s angry video game reviewers, it was, at the time, in desperate need of a killer in-house developed title. The previous two, Trevor McFur in the Crescent Galaxy and Club Drive were both critical and commercial flops, and the team was searching for its Sonic the Hedgehog moment. This led to some delightfully silly ideas, my personal favourite being a game starring an alligator lawyer named Al. E. Gator. Most of these suggestions were shot down by the design team at Atari, all of whom quite rightly thought they were dumb. That was until one of the junior artists put forward a concept.

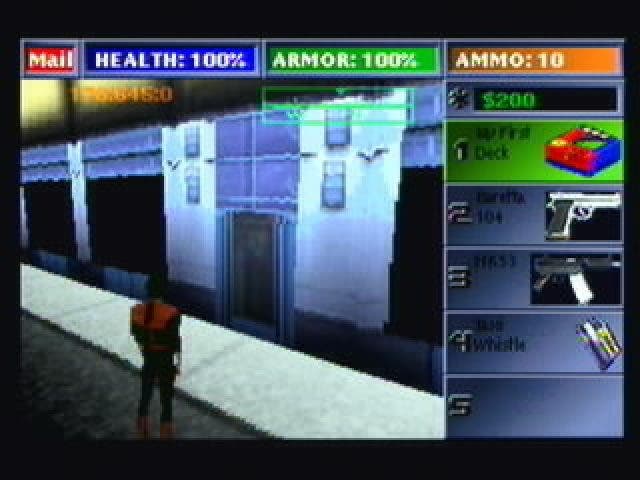

The proposed title would be a cyberpunk role-playing game, inspired by novels such as William Gibson's Neuromancer and pen and paper RPGs such as Shadowrun and Cyberpunk 2020. As a fully open-world, 3D action-adventure with a third-person viewpoint and the ability to interact with every NPC, Black ICE\White Noise would have been a truly revolutionary title. You could enter any building, talk to scores of NPCs, and even open up your 'deck' to read emails, make calls, and hack into the city's electronic infrastructure.

"If we had been able to create the game we wanted Black ICE to be, it would have been a landmark title," insists BJ. Speaking to me almost a quarter of a century after the conception of Black ICE, he reminisces over just how ambitious the project was. "I've never seen another game that early that was able to deliver an open game world from a CD, with no load lags or breaks in gameplay, to transition to a new level."

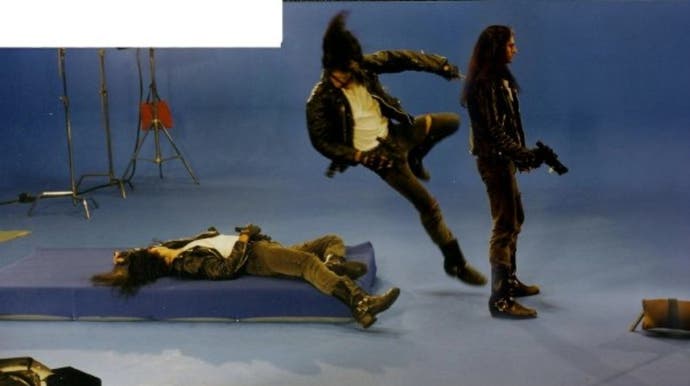

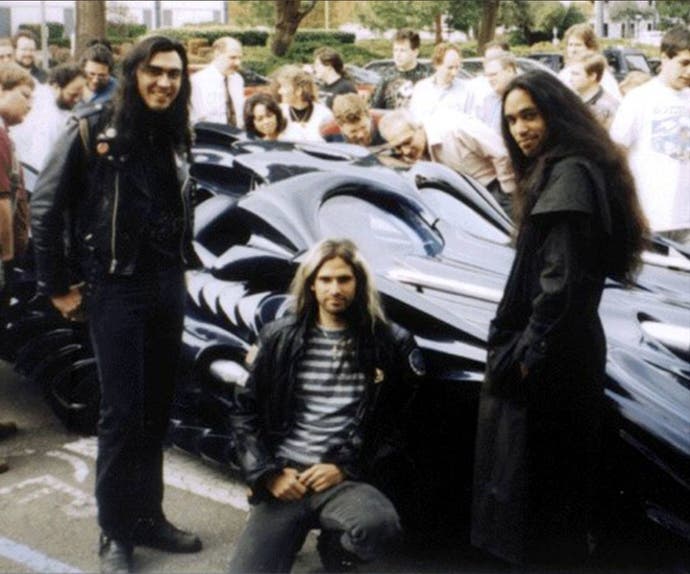

If anything, BJ is being modest. Black ICE's initial proposed release date was Christmas 1995, meaning it would have pipped Grand Theft Auto 3 to the post by six years and Deus Ex, that most revered of cyberpunk classics, by a little under five. In some ways it would have been a product of its time, making use of live-action video for branching dialogue in cutscenes (as opposed to CGI), for example. Nevertheless, Black ICE\White Noise would almost certainly have been a groundbreaking achievement, boasting features the industry wouldn't see until a whole console generation later.

Unfortunately, there were a number of roadblocks standing in the way of Black ICE's success and one of them was the gaming goliath itself, the Atari Corporation. "It mostly comes down to the attitude they had towards games," explains BJ. "They saw them as a 'necessary evil', mere bait used to sell the Jaguar hardware, rather than the primary reason anyone chooses one console over another." BJ talks at length about how the Jaguar team was focused solely on the architecture of the machine, with no understanding of what games required. He describes Atari's attitude as putting all its eggs into the video capabilities basket, ultimately hamstringing the machine with far too little RAM and no way to save games in progress.

Even the very concept of Black ICE\White Noise, an idea that would seem to be a no-brainer today, was a struggle to get past the suits at head office. "I suggested we could make an open-world cyberpunk RPG adventure game, not unlike the table-top RPGs my friends and I played on weekends," explains BJ. "I got the impression none of the execs had any idea what I was talking about, but they agreed to let me put together a proposal. The idea was you would interact with the people you found in the world by colliding with them, launching a branching full-motion video interface that let you have fairly sophisticated conversations. We put on a dog-and-pony show for them, and again, they didn't seem to understand what we were talking about, but they could see it was new and original, and we were excited about it. They sent the pitch to marketing for focus testing. The kids in the groups went nuts for the idea, and the company shrugged and gave us the green light."

Looking back, BJ views the fact he was given command of an entire project as evidence of just how ridiculous Atari's attitude towards game development was. "I had never worked in games before Atari, and I started as a mere digital production artist. There is no way I should have been able to talk my way into being part of a project of my own, and I was in way over my head. The very fact I was able to take advantage of a decision vacuum that way is an indication of how crazy things were there."

This all might seem ridiculous through a modern lens, but you have to understand the mindset of Atari executives in 1994. They were already the old boys of the gaming world, having released the Atari 2600 in 1977. They'd seen their dominance falter during the video game crash and were now playing catch-up with Sega and Nintendo. To make matters worse, 3DO, Phillips, Sony and the mighty Sega and Nintendo themselves were on the verge of launching their own 32-bit consoles, while Atari's computers were facing stiff competition from Amiga and IBM.

Atari's owner at the time, Jack Tramiel, is something of an industry legend. Having got his start making typewriters and calculators, Tramiel would go on to be seminal in the home computer world, bringing us both the Commodore 64 and the Atari ST. It has, however, been suggested that software was never his focus. In fact, one former employee went on record to say that to Tramiel, "software wasn't tangible. You couldn't hold it, feel it, or touch it, so it wasn't worth spending money for." To be fair to Atari, it was known for producing top of the range gear and it seems reasonable it would want to play to its strengths. After all, if you've got the best toaster on the market, it's none of your concern what kind of bread your customers put in it.

However, Jack Tramiel's son, Leonard, recalls things somewhat differently. He was directly involved in the hardware side of the console, working with developers, both internally and externally, to create software tools for the Jaguar. Few people have a better understanding of the console's capabilities than this man and even BJ describes him to me as "probably the smartest guy at Atari".

For Leonard Tramiel, Atari was not negligent of software, but was aware of their strengths and weaknesses. "We simply thought the best games were likely to come from external developers, so not that much attention was paid to internal efforts," he explains. At the time, the industry was beginning to embrace the 'shaver and blade' model of making money. Put simply, the idea was you sold your hardware or console at a loss, then made your profit by selling software and games. "Atari didn't have that understanding of the market when the Jaguar was designed, so we were late in getting the software world involved," Leonard states, before admitting "and when we did we weren't very good at it!"

Leonard does agree, however, that BJ was inexperienced. "One of the things that wasn't done well in any of the internal game efforts, including the ones I was in charge of, was forecasting budgetary needs so these kinds of things would not become shop-stoppers. That may be a good example of where BJ's inexperience in a role like that was a problem." From Leonard's perspective, and the perspective of his father, this wasn't unprecedented though. In fact it was often desirable. "My father was well aware that sometimes you have to just trust your gut and allow people to grow into a task they haven't done before. This often results in a rough ride, but it also allows some pretty remarkable things to get done."

From the perspective of the Black ICE team, however, this all led to a self-destructive attitude at Atari, where every last penny's worth of resources and man-power had to be fought for. Initially, Nine Inch Nails' Trent Reznor was slated to compose the soundtrack for the game, but Atari low-balled him, causing the band to back out. As the demise of the Jaguar drew ever closer, and Atari's financial position worsened, members of the Black ICE team were constantly being pulled from the project to finish off other games that needed to be shoved out of development and onto store shelves.

Still, it wasn't just Atari's lack of modernity that stood in the way of Black ICE's development. Both BJ and Chris Hudak acknowledge they just weren't mature or experienced enough and neither was the industry. It's easy to look back on their strip club visits and dart-gun fights as evidence of this, but for BJ in particular, the issue ran deeper. "We made it all up as we went along, driven by, among other things, pure arrogance," he explains. "My people skills and diplomacy were terrible, and I no doubt pissed a lot of people off by being far too candid and direct when dealing with the higher-ups."

BJ would later go on to work on the original The Sims at Maxis. There he realised the extent of both his and Atari's failings in creating a productive work environment. Looking back, he compares making games to gardening, musing on how "it needs an uncrowded patch of fertile soil, rich in nutrients, lots of water and sunshine, and it has to be protected from pests while it's young and vulnerable".

"You can't expect to grow prize-winning roses overnight," he concludes, before adding: "at Atari, we could only grow crabgrass."

Chris Hudak is more candid about his feelings on 90s Atari culture, bemoaning "the office overnighters, the crunch, and the awful, amateurish personalities". He adds he's fairly confident little has changed between now and then, expressing dismay it's "unfortunately still alive and well in the game-dev space".

By late 1995, all of the penny-pinching, lack of experience, and adolescent antics had taken its toll on Black ICE, eroding away at the innovative ideas and making it a shadow of the concept it had been just a year earlier. "In a lot of ways we were fortunate Atari went bust before we could finish," laments BJ. "The version of the game we would ultimately have released to the world would have been an extremely pale remnant of what we were going for."

Most retro enthusiasts know what happened next. Atari, having crushed under its own weight, found itself without a sellable product. The company was sold multiple times between 1996 and 1999, its name disappearing from the market. It would later be acquired by Infogrames and go on to carve out a decent reputation as the developer of PC titles such as the D&D-based Neverwinter Nights.

As for the team behind Black ICE, BJ West's work at Maxis involved creating the visual design for the first two The Sims games. Looking back on his time at Atari, he's surprisingly thankful for the baptism of fire he received. "It forced me to learn about game development and project management in a hurry, and gave me an education no university could provide at any price," he says. "It also forced me to examine what was really important in designing games and made it clear to me that nothing is more important than the player experience. It also introduced me to a small army of amazing people, most of whom I still consider family, even now."

Chris Hudak would go on to have a diverse career. He's both written and acted in films, as well as worked on novels and short stories. Since 2014 he's travelled, mostly in Korea, Thailand and Japan. He even had a brief stint taking care of penguins at the San Francisco zoo! Looking back on his time at Atari, Hudak's recollections are an almost polarising mixture of fond camaraderie and frustrated constraints. "We bitched about our daily lot in terms of struggling with logistical limitations and funding. But we definitely soldiered on through it with as sunny an outlook as possible. We made semi-weekly pilgrimages to Toys R' Us to load up on those colorful, plastic, cheap-ass, ready to break at a moment's notice dart-guns, so we could have those therapeutic, inter-office melees the suits clearly hated, and we laughed our asses off about it!"

Leonard Tramiel is still a familiar face at classic computer conventions, as well as a highly respected authority on hardware, both new and old. Looking back on his work with the Jaguar, he takes a philosophical, but honest perspective. "The Jaguar was an amazing machine and I'm quite proud of it and of my contributions to it. I'm just sorry we didn't understand the software development business well enough for the machine to succeed."

The story of Black ICE\White Noise is a deceptively melancholic one, the saga underpinned by the fact a series of blunders and poor decisions on both sides robbed the world of what might have been an important part of our hobby's history. That isn't to say anyone involved should feel bad about Black ICE's demise. In fact, these occurrences are important. The game and its eventual cancellation serves as a cautionary tale that attests to the sad truth that no matter how passionate and talented you are, sometimes your work will go incomplete and unrecognised. Beyond an unfinished build on BJ's website, this once potential masterpiece has almost no online presence, barely any mentions on YouTube or the gaming internet, and exists as a footnote on a few ageing Atari fan sites. For Black ICE\White Noise - and Atari - what might have been will forever remain in the realm of imagination.