Picture books and video games: a backdoor into childhood

There!

It must be the sense of anonymity that compels people to share secrets with strangers. I was having a conversation with a woman in a bookshop when she decided to tell me something I could tell was troubling her about her nine-year-old son. "The thing is," she said (she had a twitch in her lower lip), "he's a bright boy, but... he still likes books with pictures in." As a children's bookseller, I hear things like this all the time. Proud parents like to tell me that their children no longer 'need' pictures in their books, as though they had just collected their children from a clinic specialising in the treatment of visual withdrawal. Sometimes it's the children themselves that need reminding: "You don't need books with pictures in- remember?" In either case, the message seems clear: pictures are mere training wheels for text, and the sooner we're done with them, the better.

This idea often goes hand-in-hand with the view that children's literature is merely a simplified version of adult literature, the literary equivalent of a Playmobil fire engine. On the contrary, I think picture books in particular have their own grammar and perspective that you simply don't find in such abundance elsewhere. In fact, I would argue that if picture books have a torchbearer anywhere in the creative arts, it's not to be found in literature all. For that, you would need to look to video games.

In the heyday of printed games magazines, we ate with our eyes. In the absence of video, we studied still images and tried to animate them in our minds. It's hard to imagine now but seeing a game in motion for the first time really was just as big a revelation as how it played. In the years since, video games have made art critics of us all. We even learnt a new vocabulary to talk about them: references to pixel density, shading, style and perspective made themselves at home in even casual conversation, and how could they not? Try explaining these four images without them:

Video games thus provide a level of engagement with visual art most people never get to experience once they've 'outgrown' picture books. Even in the internet age, a game with a distinctive art style still has that power to grab a player's attention and make them ask: What are you? How do you work?

People (adults and children alike) respond to picture books in much the same way. The work of David Litchfield, for example, never fails to capture people's attention, and it is easy to see why:

In Lights on Cotton Rock (above), a spaceship evoking a gumball machine descends upon a clearing in forest; in When I Was A Child, a grandmother and child sit by a sherbet pink lake; in The Bear and The Piano, sunbeams spotlight a bear in a tuxedo leaning over a piano. The varied textures, digital effects and distinctive colour palette bring to mind the bewitching art style of Moon Studios' Ori games.

While Ori belongs to a special genre of game that actively requires backtracking, I think it's fair to say of most games that they invite us to linger in their spaces. While prose cannot help but push us forward word by word, cinema frame by frame, the default state of a picture or video game is inertia. The world, or at least its aperture, stands still until you move it. So, not only do picture books and video games share a focus on the visual, by their very nature, they encourage us to explore their visuals at our own pace.

Another way in which video games echo the pleasures of picture books is their commitment to exhausting every inch of an idea before letting it go. One of my favourite examples of this is Nanette's Baguette by Mo Willems', a picture book whose text almost entirely rhymes with the word 'baguette'. As you can imagine, this is a text with a difficulty curve.

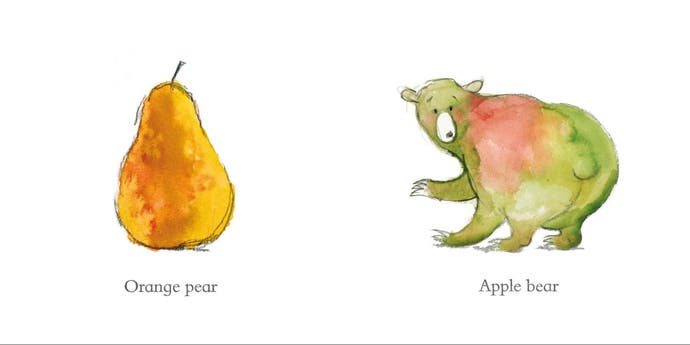

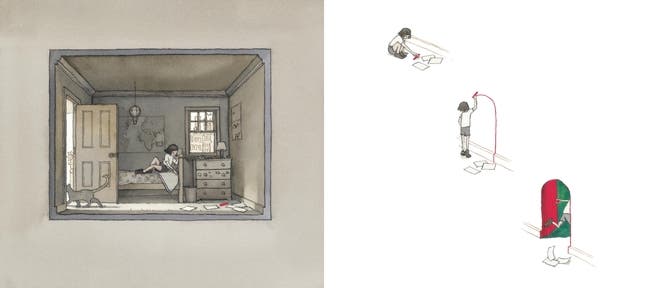

Things start off simply enough, though you're soon juggling lines with multiple internal rhymes ("Will mom regret she let Nanette get the baguette?"). But as soon as the idea reaches breaking point, it ends. For a more visual example, we might look to Emily Gravett's Orange Pear Apple Bear, a picture book told in four words.

As the words are rearranged, the illustrations keep pace, resulting in a gentle cross-pollination of ideas. Once the combinations have been exhausted, a fifth and final word is used to bring things to a close: There!

So many of my favourite picture books are like this: they take a simple idea and play with it until it breaks. So many of my favourite video games are like this, too. Super Mario Bros is a game about a jump. Portal is a game about a portal gun. The designers ask themselves, what can we do with THIS? And the very best of them know that when there is no new answer to that question, it's time to call it a day. There! This explorative design philosophy inevitably leaves a mark on a game's narrative structure. In Papers, Please, for example, the story unfolds as the gameplay loops, growing in moral complexity alongside the game's mechanics. The question should you let this person pass? is the same each time, but, like the length of a chasm, or the velocity required to clear an obstacle, it is the shifting context that gives the game shape.

If you spend enough time comparing video games to picture books, you'll find some surprising similarities in the stories they tell. Even a story as bleak as Papers, Please has its picture book cousin. In Don't Cross The Line (Isabel Minhos Martins and Bernardo P. Carvalho ), a guard stands at the centre of each spread to prevent characters crossing from one side to the other.

"I'M SORRY, I'M ONLY OBEYING ORDERS," he says, explaining that the other side of the page is reserved for The General. As in Papers, Please the guard is both the instrument of an oppressive state and a victim of an oppressive state, provoking feelings of contempt as well as pity.

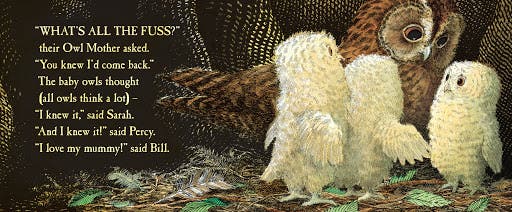

Another example: towards the end of Ori and The Blind Forest, we learn the tragic backstory of Kuro, the game's primary antagonist. A devoted mother, she spends her days gathering food for her offspring. One day, events beyond her understanding cause the forest's Spirit Tree to release an intense flash of light, destroying her nest. She rushes home, only to find her offspring killed, setting her on a path of vengeance.

This reads very much like a dark inversion of Martin Wadell and Patrick Benson's modern classic Owl Babies in which three owlets, lonely and afraid, huddle together while they wait for the mother to return from the hunt.

I believe similarities such as these are more than just coincidence. I think it has something to do with the fact that picture books and video games excel at telling stories from a particular vantage point. It's all a matter of zoom. Their often limited storytelling space privileges 'Big Ideas' over, say, the intricate portraits of life that novels make possible. Perhaps my favourite example of this is Journey - the title alone invokes an aggregate perspective on life. It presents a tale shorn of life's details, a wordless experience where bodies are concealed beneath robes. In Aaron Becker's book of the same name, a girl uses a crayon to draw a door into another world. Becker's Journey is also wordless, and even features a silent encounter with a secondary character who becomes an unexpected source of companionship. It seems that when we tell stories at this altitude, certain ideas crop up time and time again.

I still think it is a mistake to 'outgrow' picture books. I much prefer Maurice Sendak's take: "Kid books... Grownup books... that's just marketing". Thinking of things left behind in childhood reminds me of Phillip Pullman's essay on Heinrich Von Kleist's On The Marionette Theatre. In it, he outlines a vision of adolescence that became central to his fantasy series, His Dark Materials:

"Having eaten the fruit of the tree of knowledge, we are separate from nature because we have acquired the ability to reflect on it and on ourselves - we are expelled from the garden of Paradise. And we can't go back, because an angel with a fiery sword stands in the way; if we want to regain the bliss we felt when we were at one with things, we have to go not back but forward, says Kleist, all the way round the world in fact, and re-enter Paradise through the back door, as it were."

And that, I think, is what video games have to offer us: a backdoor into childhood that is separate from nostalgia, giving us the opportunity to once more play with pictures, to see the world from afar, and do all this with all our intellect and experience intact.