Hardspace: Shipbreaker is about dismantling the relics of Homeworld

Cutting content.

The prow of the transport peels away like the galaxy's biggest slice of layer cake, shorn edges still white-hot from the touch of my laser. A dragon's haul of cosmic junk is revealed: corridors lined with zero-G seats and computer displays; outer hull compartments packed with relay boxes and fat, juicy cannisters of coolant. I set to work with a will, snipping at connecting struts and using my electromagnetic grapple to whip freed components into the hoppers along the flanks of my salvaging bay.

Aluminium decking goes into the furnace, nanocarbon panels into the processor for freezing and shattering. Some pieces are too massy for me to drag around by myself: I attach these to the bay walls with elastic tethers, tugging out giant satsuma segments of hull. More intricate objects such as thruster cores are flung down into a wireframe energy palette, suspended like an enormous sifting pan hundreds of miles above the waters of a ravaged Earth. As the transport disintegrates under my hand, a corp AI tracks the weight and dollar value of each item of salvage, while my foreman, aka "Weaver", reminds me of the time left in my shift.

Not everything can be harvested from outside - I'll need to breach those hull compartments and melt hidden joists before I can carve up parts of the exterior. Venturing into a decommissioned spacecraft has its perils, needless to say. I've already completed the all-important first step: decompressing the vessel in a controlled fashion, so that it doesn't burst like a rotten stomach when you crack the lid, flinging precious scrap (and yourself) into deep space. When it comes to smaller ships, that means entering via the airlock, providing it still has power, then locating an atmospheric control unit to vent the stagnant air. Larger ship classes are trickier to break into, but after only a few hours with my Early Access build of Hardspace: Shipbreaker, I don't have the clearance for them yet.

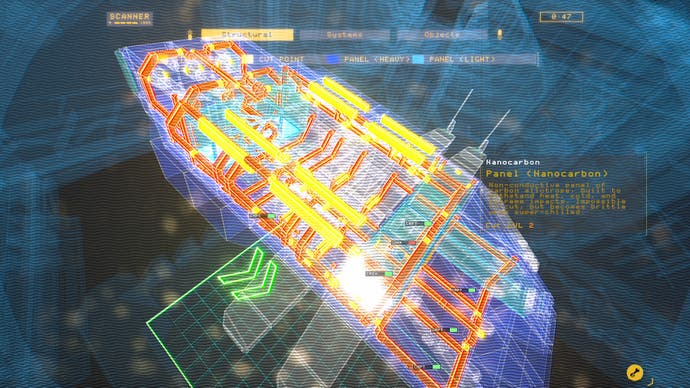

The darkness within the transport is full of dust and debris, recalling the inside of Ripley's escape pod at the start of Aliens. Old food packets bounce off my visor as I fire my jetpack inexpertly, holding control key to reset my momentum after each clumsy manoeuvre. I switch to my helmet scanner, which reduces the ship to a ghostly tracery of passages with valuable objects colour-coded by type and material. It's wise to pause and scan regularly, even when stripping down ship types you're familiar with. Smaller vessels house circuit boxes that may shoot lightning in all directions when meddled with. Bulkier craft are threaded with volatile fuel lines, and may also harbour pockets of radiation.

There's equal incentive to hurry, however. After all, I'm on the clock here. Every second of caution is a second I'll regret if I can't recoup the shift's expenses, and find myself adding to the billion dollar debt that got me into orbit. I have around a minute to salvage the greatest trophy of all: the reactor. Nestled above the transport's engines, it'll earn me a cool half million. Providing, that is, I can ferry the item from its housing to the palette before it explodes.

The safest way of doing this is to snip away the surrounding hull, allowing you to yank the reactor loose and launch it into the palette with a single flick of the wrist. You learn to tackle this last, completing objectives such as salvaging a certain weight of nanocarbon that double as opportunities to clear a path for the reactor. In this case, however, I don't have time to do any more starship butchery. So I try to fumble back to the airlock with my prize, cursing my inability to shorten the beam of my grapple, and manage to get the reactor lodged behind a chair. One nuclear detonation later, I'm back in my rental habitat wearing a freshly cloned body. The replacement body costs a pretty penny, but the loss in terms of salvage is greater. I'll need to work extra-hard on my next shift.

Outer space has proven fruitful terrain for videogame stories about unsafe, dehumanising labour. Shipbreaker - which enters Early Access today - joins the likes of Tacoma, Objects in Space and The Outer Worlds in conceiving of the final frontier as an environment spawned and operated by corporations with token respect for human life. In this case, that would be the Lynx Corporation, with whom you'll sign a contract on start-up that (amongst other things) requires you to embrace the prospect of being slowly irradiated by the tools of your trade. Everything you use as a proud Lynx employee must be paid for separately: from the habitat that serves as your mission and customisation hub, to the jetpack fuel and oxygen you'll consume on mission. Your debt is forever in your eye, embossed on your save file and stamped in red below your takings from each shift.

In theory, you don't have the luxury of thinking about the ships that fall under your knife. The pressure to optimise is too great - even a shift in which you don't nuke yourself may prove ruinous if you do things out of order, or spend too long coaxing some heavy object into the furnace. But it's impossible not to, because to dismantle something with care is also to feel the care with which it was made. In this way, and for all the need to turn a profit, the game articulates a kind of solidarity with those unseen shipbuilders that extends, curiously but persuasively, to the designers at Blackbird Interactive.

These aren't just any ships. They are Homeworld ships, in spirit if not in name: functional yet elegant craft made up of dusty matt panes with minimal greebling, painted in quietly luscious shades of Venusian yellow, Martian red and Neptune blue. Much as Homeworld's larger craft were designed to help landlubberly RTS players orient themselves in the game's bewildering 3D spaces, so these sturdy, symmetrical designs are easy and pleasant to read. Their angles positively beg to be cut into and teased apart.

Blackbird is, of course, the current custodian of the Homeworld franchise along with Gearbox Software: it was founded by members of the IP's creator, Relic Entertainment. I wonder how it must feel to design a game about dismantling your own work, two decades on and a studio away. It certainly gives Hardspace a personal resonance for me. I remember starships like these from the combat volumes of the Diamond Shoals and Tenhauser Gate. I remember ranging them against the warfleets of the Taiidan Empire, late at night on a CRT display. Years later - and having amassed a fair bit of debt myself - I circle the cooling, long-journeyed relics of those games, carving up my childhood memories for a pittance.

You don't need that personal attachment to understand the poignancy of Hardspace's ships. Even when the vessels in question are barely more than cockpits strapped to rockets, they are living and work environments, marked by sympathetic principles such as firm divisions between areas for pilots, passengers and cargo. They are things other people once inhabited and relied upon, spaces for stories. Some ships contain more explicit narrative artefacts that let in a little of Hardspace's wider universe of people and things, glittering in the fastness beyond the walls of your salvaging bay.

Supposedly “fantastical” stories about mistreated labourers risk being romanticisations of the drudgery that already prevails for an enormous number of people. For all the sci-fi set dressing, Hardspace's representation of corporate servitude is hardly lightyears beyond the experiences of, say, the workers who make clothes for companies like Primark, or the miners who supply precious metals for the manufacture of videogames consoles. Even the idea of being cloned on death is really just a metaphor for the ease with which workers in such industries are replaced. There's a sense, as with The Outer Worlds, that you are indulging in a kind of morbid poverty tourism, taking pretty products apart while laughing at the malevolence of the ideological machinery that engulfs you.

All the same, I think Hardspace is valuable for the emphasis it puts on discovering how a thing was made and who made use of it, even as you're obliged to melt it down into currency. Cultural production under capitalism generally seeks to hide the circumstances of an artefact's creation: the hope is always to present the commodity as if it came from nowhere and no-one. Dissecting these lovingly assembled vessels isn't just an engrossing zero-G physics puzzle, though if that's all you want from the game, it amply delivers. It's an act of appreciation, heightened by an awareness of the developer's previous projects, that can't help but restore a little of the humanity corporations deny.