Getting off the Road: the apocalypse games of Cormac McCarthy

What videogames have learned from a deeply pessimistic vision of America.

Games abound in the novels of Cormac McCarthy, though it might take you a while to notice them. Partly this is because they're small: tossed coins and chess pawns in the shadow of landscapes that stretch forever, the big skies of America bearing down remorselessly on casts of lost cowboys, hardy drifters and philosophical killers. And partly, it's because the games are enormous, almost too large to see. They loom within the mesas and canyons of McCarthy's prose like krakens mistaken for the ocean floor.

Consider The Road, the Pulitzer-winning tale of a nameless father and son, journeying toward the coast of an America reduced to ash and bone. It's a grinding descent of a book, weeks of shuffling despair scattered with violence like drops of blood in brackish water. Perhaps McCarthy's best-known work today, its vision of climate disaster has shaped the rise of a remarkably despondent breed of post-apocalyptic video game - neurotically focused on tiny acts of subsistence, rather than the neo-barbarian excess of games like Rage 2. The Road isn't all gloom, however: it also harbours glimmers of playfulness. Games of quoits with scavenged steel washers. A round of checkers by candlelight. There are card games, too: Old Maid and Whist, played with a deck missing the Two of Clubs, together with sillier games of the father's devising, like "Abnormal Fescue".

Cards, here, are more than cards, much as characters are more than people: all are symbols in McCarthy's torrid mythology of America. The missing Two of Clubs reflects the isolation of the protagonists, who in turn resemble a final hand in a card game aeons in the playing. The cards are also a mechanism of time travel, a way of conjuring a bygone world for a child born after the collapse and a man unable to think outside the exhausted present. These wistful reminders are a distraction from the practicalities of survival, but they are necessary, the book suggests, if those practicalities are to have any meaning or momentum. They are "orders in creation", in the words of Blood Meridian's judge Holden - "put there, like a string in a maze" to give shape to an indifferent universe.

Set in the mid-19th century and generally regarded as McCarthy's best book, Blood Meridian hasn't captured the imaginations of game developers like The Road, but its spectre haunts the latter's apocalypse and is vital to an understanding of its games. In Holden's estimation, "men are born for games", war being "the ultimate game because war is at last a forcing of the unity of existence", fixing players symmetrically as victors or the slain. This creed animates a country-wide spree of murder, rape and mutilation over which the "vast abhorrence of the judge" presides as chronicler and enabler. Where The Road scours the wreckage of the United States, Blood Meridian excavates its birth in the shambles of the borderlands, those usefully "lawless" regions beloved of open world shooters. It's a vicious debunking of Wild Western cliches, as violently coloured as The Road's devoured and devouring America is pitilessly grey.

To speak of beginnings and endings is to miss something crucial, however. The Road and Blood Meridian mirror rather than following one other, each dominated by a journey and hinging on the tension between old and young men: Blood Meridian pits the judge against the Kid, who falls in with Holden's gang of scalp-hunters after an ill-fated expedition to Mexico. The trick to these mirrorings is that Blood Meridian, too, is a post-apocalyptic story, because in McCarthy's eye, the United States has always been a post-apocalyptic land, born of genocide and dispossession. The source of The Road's Earth-killing catastrophe is never given, which lends the disaster an open-endedness that loops back to the atrocities of America's settlement. Time, in each book, hovers on the edge of meaninglessness. As the father remarks to himself, "there is no later" because everything reverts to the same "common provenance in pain". The judge, meanwhile, styles existence “a trance” with “neither analogue nor precedent”, in which everything is possible and not even the blood-soaked past can be taken for granted. As he asks the Kid: “where is yesterday?” Rather than distinctions in time, this account of history is made coherent by adversarial rituals that reflect a fundamental inhumanity - combat, conquest, the playing of games.

McCarthy's tendency to portray violence as just elementary stage machinery in the cycling horrorshow of reality invites translation into the language of big budget action games. Blood Meridian's litany of killings is echoed by the endless, perfunctory slaughter of Red Dead Redemption 2, which riffs on the novel to the point of having journal entries written in passable McCarthyese. The Road's campfire games suggest a brighter outlook, but they orbit a larger game of narrative archetypes, invented by the father, which is every bit as brutally reductive as Holden's warmongering: "good guys", "bad guys" and a child who becomes a precious object out of scripture - a quest item, "glowing like a tabernacle".

This larger, unspoken game gives the pair rules to live by, but it also reflects an inability to make anything of a universe that isn't as cold and spent as it seems. The book begins with the father waking from nightmares of a creature with "eyes dead white and sightless as the eggs of spiders" and sweeping his binoculars over a "barren, silent, Godless" countryside. The desolation might seem an indisputable fact, but it's not clear the father is capable of seeing anything else. Paralysed by loss, he has become the co-architect of a reality shrunk to a "raw core of parsible entities" - food, water, shelter, firewood, bandits and bullets.

As a means of constraining the landscape's possibilities, this framing evokes both the open world protagonist tagging objects through a spyglass and the imperial anxieties of Holden, who is forever annotating and categorising his surroundings in a bid to become “suzerain of the Earth”. It's left to the boy, inevitably, to seek out the future his father cannot see. We never quite meet with that future in the book, which suggests a writer conceding the limits of his own imagination. McCarthy's handful of magazine profiles reveal him for an incorrigible hermit and pessimist: he has argued that the notion of progress is a sham, that humans are inherently violent, that "living in harmony" means "giving up your soul, your freedom". Conceived during a lonely motel vigil, as McCarthy pondered what the future held for his own son, The Road occasionally reads like a confession that its author is unable to envisage a world where human fellowship is more than a childish dream. Neither the father nor McCarthy himself can picture this journey's end. The point is to pass the torch to somebody who can, and the book ends with frail hope on an image of trout in a brook, their backs adorned by “patterns that were maps of the world in its becoming”.

If The Road concludes by pointing towards another world, many McCarthy-influenced videogames have proven more interested in replaying the father's struggle than exploring the child's future. "You need to get off the road," is the novel's most telling line, but in blockbuster games such as God of War 2018 we sleepwalk along it - a bitter, ageing man shepherding and stifling a child freighted with the prospect of tomorrow. Partly, of course, this is because the father's struggle is so gripping. The book invests the quintessentially videogamey routines of scavenging and fighting with grandeur and pathos; its violence is sparing but vividly described. Survival simulations such as The Long Dark have benefited immeasurably from its portrayal of tenacity and torment. But there's also a demographic question at stake here. Published in 2006, The Road was a timely novel not just because it is about enduring an ecological catastrophe. It also augured the infamous "Dadification" of games, as the creators of story-driven action franchises sought to shore up the centrality of leading men while ruminating upon their own experiences of fatherhood.

The Road is a useful reference point for any developer looking to reboot videogame masculinity because it is fundamentally about the transfer of agency between a man and a boy (the only significant female character is the dead mother, who appears as an erotic memory of defeat). It makes space for guilty reflection on the failings of a particular generation of men, while consolidating the pre-eminence of masculinity at large. Naughty Dog's The Last of Us appears to stray from this dynamic - a near-retelling of The Road, spliced with bits of Sin City and WW2 fiction, it gives your leading man a surrogate daughter. But it reaffirms the centrality of maleness in its final, despairing moments. As in McCarthy's book, the father figure is eventually incapacitated, and the child is obliged to discover herself as an autonomous being. The difference, of course, is that Joel rises from his sickbed to take back the reins, depriving Ellie of her most significant choice in the game and returning her to the status of a quest item.

This year's The Last of Us: Part 2 is theoretically Ellie's tale, with Joel very firmly out to pasture, but in practice it's a story about daughters battling the gravity of fathers who haunt them not just in the form of objectives and flashbacks, but in the very methods and tactics by which they navigate and fight. The expectation of familiar mechanics and scenarios that attends on any sequel intersects, here, with the extension of toxic paternalism beyond the grave. These are fathers who are all the more overbearing and suffocating in death. For all Part 2's efforts to leave them behind, to cultivate new homes and different concepts of family, theirs is the only universe each game allows us to see.

So how do we get off the road? What other possibilities exist in McCarthy's doom-ridden conception of America, and which games bring those possibilities to light? One game that puts a more invigorating spin on the book's trudgery is The Flame in The Flood, a "post-societal" survival roguelike. It, too, is a perilous journey to the coast, grounding symbolism and metaphor in the material threat of starvation and disease. As design lead Forrest Dowling told me, the game also borrows McCarthy's trick of refusing to offer a cause for the apocalypse. "As a work it didn't care about what came before, it was the story of two people in a moment. That is something that we tried to emulate."

There are no parental dynamics to reckon with, however: your companion is a rescue dog who transcends the fiction, returning to escort a new survivor each time you go under. And rather than hauling a shopping cart across an eternity of tarmac, you are riding a river, a gambolling work of procedural generation, altering its course between playthroughs, shuffling and reshuffling a deck of ports and encounters.

Where the Road's namesake is a deathly thing, a crumbling icon of modernity finding its way inexorably to places emptied of people and significance, the river is more creature than structure, knitting itself together off-screen as you barrel along in your raft. As a geological entity and as a collection of gameplay permutations, it expresses the promise of change. While Dowling confesses that he hasn't read any of McCarthy's other books, the game perhaps has less in common with The Road than Suttree, a tattered Gothic picaresque about a man who lives on a riverboat, marinating in landscapes that are polluted and grotesque yet far from dead. "In these alien reaches, these maugre sinks and interstitial wastes that the righteous see from carriage and car another life dreams."

The sense in McCarthy's novels that time itself is collapsing around some timeless idea need not be nihilistic, as we find in Space Backyard's Like Roots in Soil. A sort of interactive short story, the game follows two figures through parallel landscapes, with players panning the view around a screen divide to expose or hide each journey. As the animation proceeds, an accompanying first-person narration weighs the competing claims of past and future. One figure is an older man in rags, carrying a seedling through a devastated city. The other is a young man in contemporary clothing, walking through what appears to be the same city before its ruin. Each journey ends before a patch of earth. Here, the old man plants his seedling. The young man, meanwhile, lingers before an enormous tree.

As Space Backyard's Maddalena Grattarola told me, what all this signifies is a question of framing. Panning the camera, she explained, allows the player "to 'direct' the game and to 'narrate' the story at the same time, granting them the freedom to decide which context would suit best each sentence" - an ambiguity inspired by McCarthy's technique of omitting quotation marks and so, challenging his reader to distinguish between narrator and character.

The tree may have been planted by the old man, as a gesture towards society's rebirth that is fulfilled in the presence of the young man. Or perhaps the old man is actually the young man, returning to the site to plant anew. Whatever your reading, the immediately proffered option to "go on", restarting the animation, robs it of conclusiveness: the two periods are visually connected, but there is no concrete sense of before and after. This isn't The Road's fatalistic return to a "common provenance in pain", however. Rather, the game is a pervasive embodiment of hope. Whenever it takes place, and whatever disasters may befall, there is always the planting of a tree.

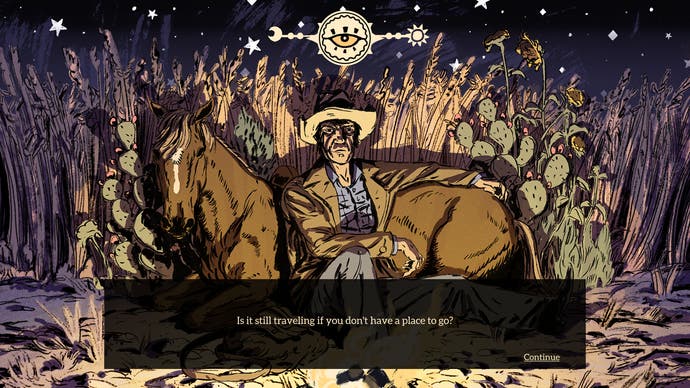

Dim Bulb's footsore epic Where the Water Tastes like Wine strikes a similar balance between optimism and anguish. A thousand-mile game of Telephone in which you gather campfire tales represented by tarot cards, it is ostensibly set in Depression-era America but includes ghostly visitations from other periods. The game holds "a mirror up to America and its past, as a way of trying to reckon with our present and future", lead designer Johnnemann Nordhagen told me, with a view to "telling new kinds of stories and weaving those into the fabric of the American story going forward". In this, it looks beyond The Road and Blood Meridian to both Suttree's amphibious vignettes and The Border Trilogy, McCarthy's reputation-making elegy for cowboys and the old West. "It's the apocalyptic aspects that interest me the least [about McCarthy]" Nordhagen confesses. "The Road is my least favorite of his books."

WTWTLW harbours a more explicit link to McCarthy in the shape of Ray, a vagrant cowpolk who is based on characters from the Border novel Cities of the Plain, but for the most part, McCarthy's influence was about "worldbuilding and the desire to try to create that same feeling of wandering a weird and dark land, where anything could be lurking in the hills and hollows." The game's geography certainly captures the mood, vast and secretive beneath a sky of mottled ink. Icons denoting stories approach with predatory slowness as you amble from state to state, the one human figure in a realm of appalling immensity.

Rather than despair, however, the game aims for a sense of "folkloric possibility", recalling an era when "the culture in a place was much more singular". Playing it is an act of weaving these local identities into a "patchwork quilt of Americanness", but this isn't the same merciless, homogenising ethic of documenting and controlling we see in Blood Meridian or the likes of Far Cry. To make headway, players must not only collect but release those stories back into a burgeoning America, where they shapeshift from mouth to mouth, returning to you in more potent, extravagant forms. You do not own these increasingly tall tales, in other words: you only travel with them for a time. This process of hearing, retelling, hearing and retelling fashions something benevolent from the landscape's histories of violence and dehumanisation, without pushing those histories from view.

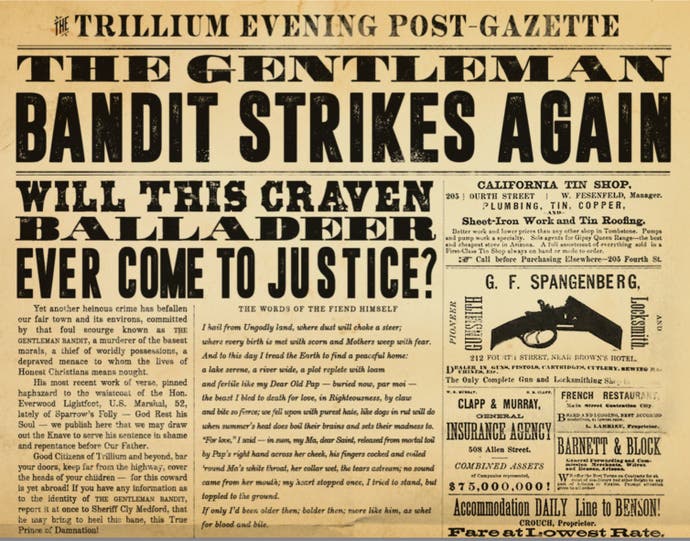

I began this article by talking about The Road's cardgames. It's only appropriate to end with a set of card games influenced by McCarthy's novels - Allison Arth's Western Cantos series, in which players write poems about their and their character's lives by drawing from a standard deck of playing cards. Arth's work trades, like McCarthy, on "classic Western tropes", but she uses these to activate "richer questions about how we process trauma, how we create fictions of and for ourselves to cope, how we other and isolate".

In Gentlemen Bandit, the first in the series, you take on the role of a notorious highwayman who always leaves a poem at the site of his kills. The game is framed as the testimony of a "legendary person who transcends time and place, and is yet struggling to find peace or solace or some kind of anchor". Composing the Bandit's “personal history of violence, woe, and dissociation" is also, however, an invitation to think about any anguish you yourself carry. Lines are written by matching card numbers and suites to an emotion and a question. Take the Two of Clubs, that missing card from The Road's deck: it gives you Fear and the question "Who needs you?" The resulting poem is always one line short of a traditional sonnet, Arth says, "because this kind of internal work is never completed".

You could summarise McCarthy's oeuvre as a tug of war between games like these, and games as conceived by judge Holden. On the one hand, there are the cosmic games of history, atrocity and landscape, endless enactments of humanity's tendency towards conquest and depravity. And on the other, there are the smaller, intimate games played by people swept up in those machinations - reductive in their turn, perhaps, but ways of shedding light on oneself and others, of gesturing toward some kind of common future amid the horror. The Road's bleakness is both cautionary and cathartic: it walks us through the idea that our planet is slowly succumbing to legacies of hatred, greed and bloodshed. But as our own ecological catastrophe advances, it's important to remember that the book isn't purely about catharsis. The point is to dream of something better.