13 Sentinels: Aegis Rim review - a heady mix of sci-fi, passion and big ideas

Virtuosity.

Here's an incomplete list of things you will encounter in 13 Sentinels: a talking cat. Time travel. Time travel, but also not really. Androids. Clones. Android clones. Memory-wiping drugs. A robot that looks like Wall-E. An underground UFO. Oh, and of course it's the story of 13 highschoolers getting into giant mechs to fight monsters.

To find out how they ended up in those mechs and where the kaiju they're fighting come from, you follow each protagonist individually. Each storyline unfolds in an achronological fashion to the other 12, so that soon it feels like you're piecing together a puzzle of stories to form a larger whole. There's Juro, a normal teenager in 1985 who starts to wonder why he keeps having hyper-realistic dreams that seem to unfold just the way his favourite sci-fi films do. Shu Amiguchi, who's talking to a famous pop star through his TV. Natsuno Minami, who travels through time with the help of the aforementioned Wall-E lookalike to save him from the Men in Black. Takatoshi Hijiyama, a young soldier who accidentally travels to 1985 from 1945 while investigating a cross-dressing spy and many more things than I have the space to mention. The separate, 30-level "Destruction" mode meanwhile consists of real-time tower defence battles against the kaiju, depicting one large-scale battle that chronologically sits at the very end of the story.

While the side-scrolling mechanics in the story section and the lovely 2D art style make it immediately recognisable as a Vanillaware game, 13 Sentinels is much more story-focused than any of its previous output. The battle sections are a good way to liven up what can otherwise feel like a very static game, but you need to be invested in the characters and the many mysteries that surround them to truly enjoy yourself. At first it's just a barrage of technical terms and names and random revelations and slowly but surely - actually, never mind, you learn everyone's names, but the finer detail stays that way, a jungle of wild ideas that's deliberately a lot to keep up with.

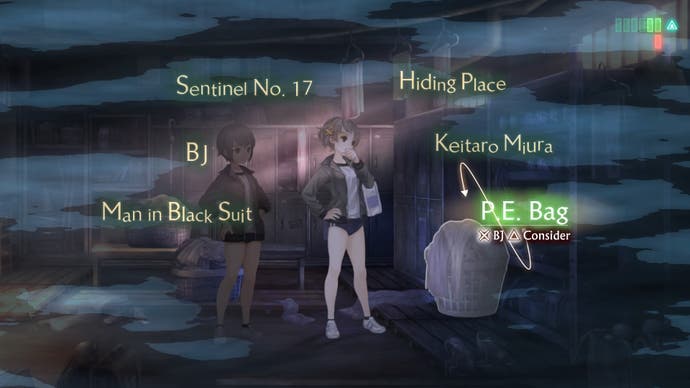

13 Sentinels often feels a lot like a visual novel, because you puzzle the story together from various keywords and events, using a system called "Cloud Sync", inspired by the menus in point and click adventure games. The cloud is a literal thought bubble holding every important bit of information a character gathers, which you can then use in conversations. Sometimes in order to progress with the story, you need to access a piece of information and then listen to the character think it over or mention it to someone else. You're never told what the next step is, which unfortunately can lead to several moments where you move from screen to screen or go through all of your keywords again in the hopes of encountering something new. Each character spends most of their time doing the same things over and over - every day in Juro's story, for example, always begins in his classroom at the end of lessons, and there are many conversations you'll have several times before a keyword triggers a slight deviation. Whenever it does though, exciting things are bound to happen, and then the wait instantly becomes worth it.

There are a few narrative downsides worth mentioning. 13 Sentinels basically has no plot to speak of - it's all world-building. Characters regularly monologue their way through huge chunks of exposition. Plot holes are often solved through a character acting as nothing else but a handy deus ex machina, which is especially frustrating when some elements only serve to make the story more complicated overall. As many Japanese games with a war setting, it can be unflinching in its romanticised patriotism. The one gay relationship in this game has to be a tragic one, as per the unwritten rules of queer storytelling in popular media, and it presents genderbending as the only option for true success of the romance, which I would find more troubling if 13 Sentinels wasn't, like all of Vanillaware's romances, a story where characters meet each other exactly once before they decide it's forever.

The real-time battles are filled to the brim with kaiju of all shapes and sizes, all represented by tiny icons, stuffing the screen until the framerate packs up and takes the next train home. You select a formation of six frontline fighters you'll control directly, the rest are on standby using defensive skills and buffs. Sentinels come in four different classes from melee to flying support mech, each class bringing different skills with it. The goal is always the same - get through several waves of enemies and protect the Aegis portal. If an enemy touches the portal or a pilot is killed, it's game over. For most of these battles, it's enough to use whatever attacks you have available that kill as many kaiju in one go as possible, and in Vanillaware-typical fashion on normal difficulty an S rank isn't so much a show skill as it is an expectation. The game is at its absolute best later on, when you have to make truly tactical decisions and invest in telling apart the different kaiju to devise a strategy. The battles I came close to losing were the absolute best ones, filled with the din of laser cannon fire, pilots rattling in their pods, shouting words of encouragement at each other.

While I was still trying to work out how to explain that this game is too much, but in a good way, along came a video by YouTuber Patrick (H) Willems, called "The Modern Class of Gonzo Blockbusters". He describes a gonzo blockbuster as "films filled to the brim with a relentless imagination", "not afraid to be silly, weird or corny" and, perhaps most importantly, movies that "want to show us as many spectacular new worlds and sights and characters as they can fit." Another important characteristic of such films is that they tend to make you say things like "wait, hold up" and "this did not just happen". As examples, he uses films such as Aquaman and Jupiter Ascending. 13 Sentinels is absolutely a gonzo blockbuster. Games have finally caught up to film. Congrats everyone, we can retire.

If you accept the baseline ridiculousness of just about anything you encounter, 13 Sentinels still feels both coherent and cohesive, most likely because many of the ingredients it uses are well-familiar. There's an undeniable 80s campiness about the whole thing, likely due to it taking inspiration from the same slew of 80s anime and films that inspired most of gonzo sci-fi, from Pacific Rim to dare I say it, The Matrix. Everything is delivered with great passion by the Japanese voice acting cast (an English dub is going to be available as day one DLC), and underscored by a great soundtrack from Hitoshi Sakimoto and his team at Basiscape, and with everyone going the full mile always you just can't help but be charmed.

It's impossible to describe anything but the game's most basic premise without spoilers, and that's what makes it so great. Yet, writer-director George Kamitani took great care in making sure players would be able to follow events - the fact that most stories take place at a high school in the year 1985 helps ground the whole experience, and even without knowing their origins, players around the world will likely be familiar with the sci-fi tropes used(which is also the kind of global appeal that lead Atlus to localise the game in the first place). Additionally, there's also Vanillaware's patented event log, and a large glossary where you can re-read any bit of information you gathered, from how phasers work to the localiser's notes on Japanese smack talk from the 80s. Everything you see on screen has narrative reasoning behind it, an obsession with detail I previously only associated with Hideo Kojima.

I think of this kind of ridiculous entertainment as absolutely essential, especially within games, because the craziness is driven by a desire to go all out. Movies and games both have reached a technical ceiling where it's really difficult to surprise audiences on a technical level, so the surprise lies in delivering unguarded, enamouring passion instead. This, above all else is why 13 Sentinels matters to me so much. Being Kamitani's passion project, two games in one made by a game of just 29 people, simply reminded me of the effort that goes into making a game. It's easy to forget about, what with developers and publishers shrouding the whole process in mystery, before we as players tend to automatically compare whatever we play with the biggest thing already out there. That way of thinking makes it difficult to enjoy the feats of ingenuity on display. A Sentinel slowly hulking onto the screen fills me with the same awe here as it would in a blockbuster movie, knowing Vanillaware's programmers had no idea how to design such sequences, but they were so essential to the vision for the game they took years to figure it out. It's a good reminder that taking risks and trying new things takes a lot out of even the most seasoned team. The noticeable effort to create a mix of familiar and the new makes it Vanillaware's best game to date, and one of my favourite games of the year.