Demaking in the year of next gen

Take a step back.

The videogames industry has always sought to define artistic achievement in terms of new technology. Every next gen console year brings with it the same old talk of bursting through constraints on developer imaginations, of "infinite" potential finally unlocked care of another few hundred pounds' worth of swishly tailored plastic and silicon. Current gen platforms are suddenly recast as emptied-out, spent, even things to be ashamed of: as Don Mattrick infamously quipped of playing Xbox 360 games on Xbox One, “if you're backwards compatible, you're really backwards."

This cycle of innovation and obsolescence is regrettable not just because it is terrible for the environment and dependent on supply chains that facilitate human rights abuses. It brings about the neglect or even active destruction of approaches to game-making that have flourished around specific pieces of hardware - this, in a creative sector that already has a brain drain problem thanks to a culture of precarity and overwork. Studios who are producing their finest games for existing "mature" consoles are obliged to learn new sets of tools. Efforts to port and preserve the titles that run on “obsolete” machines, meanwhile, are sabotaged by vengeful copyright owners who equate preservation with piracy. This year's next gen bounce offers some hope for videogame preservationists: Sony and especially Microsoft have made cross-compatibility central to their latest consoles. But the accompanying erosion of physical media - PS5 and Xbox Series S/X are the first home consoles to launch with disc-less SKUs - leaves access to those games in the hands of the corporations who run the servers.

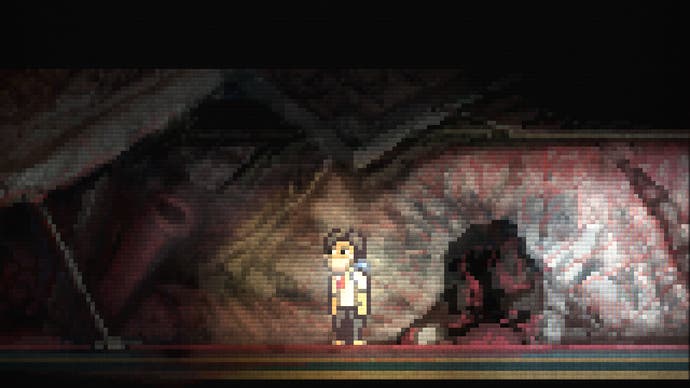

As generation tumbles after generation, it's important not just to salvage forgotten techniques and technology but to discuss other conceptions of the artform's development and history. This might take the form of a written manifesto or piece of speculative fiction - consider Emilie Reed's exhilarating Videogame History from 2024, a utopic account of a post-copyright world. But the more appropriate reworkings of videogame history, surely, are playable ones. I've spent the past few months talking to the creators of "demakes", unofficial versions of games that either run, or look as though they're running on older hardware than they were designed for. One of the best I've encountered is Soundless Mountain 2, a Nintendo Entertainment System-style 2D adaptation of Konami's PS2 horror hit Silent Hill 2, which was cooked up for a Tigsource competition way back in 2008.

Where many demakes hover somewhere between homage and parody, Soundless Mountain 2 stands out for its seriousness and meticulousness: it even has a chiptune recreation of Silent Hill 2's soundtrack, featuring contributions from Minecraft composer Daniel “C418” Rosenfeld. "Where there's a song there's a song, where there's a sound effect there's a sound effect," the demake's creator Jasper Byrne tells me over the phone, 12 years on. "Every element of the cutscene when you get the plank of wood in Silent Hill 2 is recreated, every little detail." Winning the Tigsource competition was a "big step" for Byrne, who was then employed at Frontier Developments - it earned him press connections and the confidence to try his luck as a full-time indie. But Soundless Mountain 2 wasn't just about building a profile.

Demaking Konami's colossus became a creative exercise for Byrne, akin to writing an alternate history - a fascinating exploration of how "golden age" survival horror might have fared had it lurched into motion a couple of console generations earlier. As he points out, games like Silent Hill or Resident Evil have few obvious precedents in 2D gaming (among those few are Clock Tower for MS-DOS and Sweet Home for the NES); they hinge on questions of framing and suspense that are fostered by 3D movement and perspectives. "I was just trying to see what it would be like. Would it work in 2D?"

Byrne spent many hours after work analysing and reconstructing Silent Hill 2's opening, with its long, ominous descent through hazy wooded outskirts into the eponymous nowhere-town. He carefully re-enacted the timing of screen transitions, the spacing of music cues and fade-outs. "[Team Silent] wanted to put you in a certain mindset by the time you'd got to the town. You're already in a strange place. You've been walking with all these ambient sounds around you. I'd seen the Making Of videos, but when you actually break down all the individual elements that go into the game, it really gives you a new insight."

The twist in this tale is that when Byrne demade Silent Hill 2, he had never played on a NES - he belatedly picked one up just this year. While Soundless Mountain 2 obviously trades on its association with the past, it wasn't about "nostalgia or fetishising a look", but experimenting with untried tools. As far as Byrne was concerned, the NES was a brand new machine. "It was interesting to me to explore that console, to look at the colours and see what could be done with it."

Demaking Silent Hill 2 would, in fact, help Byrne move ahead with an original point-and-click horror game he'd been wrestling with a couple of years. "I couldn't find an art style that worked, that was economical enough that I could actually produce the whole thing myself," he says. "I kept restarting it with different visual directions". One day, he decided to try a version of the game, which was initially titled Amnesia, with joystick controls and a minimalist aesthetic derived from Soundless Mountain 2's NES-based colour palette and resolution.

This change proved transformative. Byrne's game would ultimately release as Lone Survivor, a masterpiece of dread and claustrophobia that is chilling to return to in the year of lockdown. Much of the game's eeriness, for me, is down to the sense of wavering between epochs. Lone Survivor feels at once crisp and murky, ancient and modern, combining chunky, stained-glass pixels with seeping fog and shadows. Far from a straightforward work of "retro" entertainment, it is an argument for dispensing with talk of "generations" and seeing every piece of hardware or collection of gamedev techniques as equally worthy of investigation at any time.

Demakes come in all shapes and sizes. Some are technological moonshots as wondrous as anything you'll find in an Unreal Engine concept video - I can only boggle at Pekka Väänänen's adaptation of Quake for the oscilloscope, a gadget that dates back to roundabouts the end of the Second World War. Others are gorgeous novelties fashioned by artists who are looking to build an audience on social media - consider Twitter's many Gameboy mock-ups of latter-day action extravaganzas like Demon's Souls or Sea of Thieves. Many demakes are the foundations for original games: Toni Kortelahti's superb OK/NORMAL, an abstract exploration of mental illness and addiction, owes its alarming visual style to its creator's 90s-style demakes of games like GTA5 and Assassin's Creed.

Most demakes are devised for giggles or out of nostalgia, but demaking as a whole is a quietly subversive practice. Partly this is because fan games in general risk breaching copyright. Some of the most impressive demakes are, in fact, the work of software pirates like the legendary Chinese bootlegger Shenzhen Nanjing Technology Co. Ltd, purveyor of Famicom ports of PS1 games like Final Fantasy VII. But demakes also challenge the industry's fixation with the cutting edge by helping us think about cutting edge projects as more than expressions of technological "power". Besides showing us what can be achieved with older hardware, they make more visible and interrogable the artistic choices that comprise the latest games.

For the independent designer Marina Kittaka, translating a game from one platform to another gives the player a kind of "automatic" critical perspective in both directions, because you have to digest the contrast between what you know about the original artwork and what you know about the demake platform. "This accentuates the artistic choices of the demaker in an interesting way - it's almost like playing a game having already read a detailed behind-the-scenes artbook. [...] The original is sort of like "concept art" for the demake, because you see extra information and can imagine how that information was boiled down." While she has never demade a game, Kittaka pursues these concepts in the brilliant Anodyne 2, a puckish metafictional odyssey in which you warp between landscapes that resemble different eras in game design.

Kittaka's collaborator Melos Han-Tani suggests that some demakes are actually more compelling than the games they're based on, that in leaping back in time they get to the heart of ideas the "newer" game can't quite realise. He singles out Bear Parker's PS1-style demake of Sony's Death Stranding, praising its spare, empty ambience next to the Kojima game's high-end fusillade of Hollywood set-dressing. "While this feeling is present in the [original] game, the sparse landscapes and minimal soundtrack of the demake bring the feeling into focus." For Han-Tani, Parker's creation indicates "what a less visually complicated and cinematically-focused Death Stranding might feel like, which is an interesting experiment."

Parker - aka Bearly Regal on Youtube - is unusual among demakers for building most of his projects in layman-friendly game creation suites such as Minecraft and LEGO Worlds. A lifelong PS1 aficionado, his career as a public demaker began with a Dreams-based re-envisioning of Metal Gear Solid's opening dockyard cavern. It's not the first time he's mocked up the area - Parker can't get enough of Shadow Moses, returning to it again and again over the years with different sets of tools. "It's a really well-crafted environment that is packed with largely primitive shapes but enough organic detailing to give the tools a run for their money. So, I set to work on a pixel-perfect recreation and after around 80 hours of wrapping my head around the rather robust tools, I finally had a playable space I was pretty proud of."

As with Byrne and Soundless Mountain 2, demaking for Parker is a historical thought experiment. Part of his process involves playing similar games from the target era to see how certain mechanics might translate to the present-day game. He has a reputation for demaking big-name titles that are still in development, like a time-travelling scientist trying to stave off the invention of the atomic bomb - recent victims include Cyberpunk 2077 and The Last of Us: Part 2. "I'll watch a trailer for the chosen upcoming game and isolate a few scenes I think could translate well to a playable experience, as well as something online viewers may recognise in an effort to bolster the eventual video analytics, then I whip out the trusty pen and paper and start doodling, which I tend to spend a day or two doing. Once I'm happy with that, I boot up Dreams and the hair pulling begins..."

Parker calls Dreams a "wonderfully robust tool for small game creation" but concedes that simulating a PS1-era game with it is tricky. "Simply creating a basic 32-pixel by 32-pixel texture means sculpting over 1000 individual pixels, stitching them all together and ensuring the end results has the correct pattern and colour." It's especially hard to capture more specific period hallmarks like 3D texture warping, a byproduct of the PS1's programming architecture whereby polygons wobble and snap into place as you move the camera. Fortunately, Parker is an inventive guy. For the house environment in his The Last of Us: Part 2 demake, he came up with a bizarre way of simulating the flickering of a PS1 game's textures. "I crafted a giant cube that encompassed the building, set it to rotate on the spot at a ludicrous speed and removed all physical attributes so it didn't catapult the player into the ether and voila, awful-looking textures!"

If demaking has a spiritual home it's perhaps the PICO-8, a 1980s gaming console that never actually existed. Released in 2014, it's a digital “fantasy console” written in Lua and based on the hardware of the period, with a 128x128 pixel 16 colour display and four-channel audio. For all its modest proportions, the PICO-8 has amassed a sizeable arsenal of original titles - probably the best-known is the old gamejam build of Maddy Thorson's Celeste, which is hidden away as an Easter egg in the commercial version of the game. "[It's] a great platform for demakes, because it forces you to compromise when reimagining beloved games," says Paul Nicholas, aka Liquidream, a software developer from Southampton.

Nicholas is a prolific demaker - his more ambitious works include a PICO-8 version of LucasArts' old SCUMM engine, used to develop such podium-topping point-and-clickers as Maniac Mansion and Monkey Island. His most eye-catching project is Low Mem Sky, a top-down 2D recreation of PlayStation's inexhaustible procedurally generated space sim. Though not quite as cavernous as its PS4 cousin, the demake contains the raw materials for well over a trillion planets, each with its own terrain and selection of indigenous species, all packed into just 32 kilobytes of ROM. Like Byrne's deconstruction of Silent Hill 2, it is both recognisable as a homage and entirely its own thing, trading the original's rolling 3D landscapes for a gold-flecked rainbow aquarium of stars and planets.

Demaking, for Nicholas, is all about thoroughness. He often goes through Youtube footage frame by frame to piece apart complexities such as death animations, in addition to playing the game himself to understand its logic and feel. To develop his PICO-8 SCUMM engine, he tracked down LucasArts' old internal tutorial files, seeking to recreate the original application programming interface as closely as possible. All that said, “the most difficult part of the demaking process is similar to any game development project - managing the scope. Knowing what to leave in/out, what is possible in the time available.” Nicholas created most of his demakes at gamejams - time-limited community gamedev events with a specific theme. He's found that element of constraint useful. “The best approach seems to be to start small, because scope always likes to creep!"

Demaking, like other forms of retro gaming, has a precarious relationship with nostalgia. As Angela R Cox argues over at Play The Past, calling a game “retro” isn't the same thing as saying that it's old - it swaps the criteria applied to the game at release for criteria born of latter-day expectations and hindsight. More positively, this might lead to an overlooked work being reassessed and rescued from obscurity, but too often, "retro" is a byword for quaintness and cuteness. It has the effect of reinventing powerful works of art as charming primordial curiosities born of limited technology or understanding.

Byrne is concerned that certain more popular demake aesthetics reveal a similar distorting mindset - that they trivialise older games and techniques by fitting them into various nostalgic clichés. He would especially like demakers and retro developers in general to look beyond the blocky environments, short draw distances and restless, indistinct textures of PS1 games. Part of the reason the PS1 ambience is so popular, of course, is that the PS1 sold so well in its day - Byrne thinks demakers should give more love to other consoles that weren't as prosperous. "Why are we not seeing Saturn-style horrors with those particular dithered transparencies? There's a lot of different looks that haven't been explored. PS1 is an amazing console but it isn't the only way to go."

He singles out two MS-DOS games as particularly worthy of revisiting: the original Alone in the Dark - a flat-shaded game that manages to spook despite its lack of a 'proper' lighting system - and Esctatica, a werewolf fantasy that is unique for using ellipsoid rendering rather than the angular polygons of most contemporary games. "There's just something about the look of that game, all those bright colours, it's a Midsommar-type vibe, where it's all flowers and daylight but it's creepy as hell." These suggestions aside, Byrne feels that younger demakers might spend more time thinking about supporting narrative themes than visuals in themselves. "The thing I wanted to bring back about Silent Hill was that this stuff was foremost in their thoughts when they made that game," he notes. "I've never seen such a serious respect for storytelling."

As with a lot of computing hardware hype, you can trace the rhetoric of console generation jumps to the words of Intel co-founder Gordon Moore, who famously predicted in 1965 that the number of components in a chip would double every year. Moore's Law has become central to a computer industry narrative of exponential, quantifiable growth that is particularly obvious in videogame marketing. The Xbox One Series X boasts “four times” the power of the Xbox One, we are told, which in turn was “eight times” as powerful as Xbox 360. The future multiplies the past, over and over, each console reaching us at once radiant with promise and already exhausted, pre-defined as a fraction of its successor.

None of this is inevitable, however. Moore's Law is no “law” at all, of course, but a piece of “wild extrapolation”, in Moore's own words, that manufacturers have chosen to make reality for their own gain. The state of the artform doesn't have to be this endless, crumbling staircase towards another gadget. There doesn't have to be a next generation, and while there are bigger blights on terrestrial civilisation than videogame consoles, it's becoming very hard to justify the cost. Certainly, the claim that this will open up some otherwise-inaccessible possibility space for developers has never seemed more dated. Compelling, original games will doubtless be made for the PS5 and Xbox Series X, but as the greatest demakes remind us, this has nothing to do with the technology. It's all thanks to the talent and insight of the people who put such extraordinary artefacts together, whatever era of hardware they're working on.