The Solitaire Conspiracy doesn't understand what's fun about solitaire

Empty suits.

Earlier this year, Bithell Games helped UK micro-indie Grey Alien Games publish Ancient Enemy, the latest in a series of what can only be called solitaire adventures by Jake Birkett. Mike Bithell - of Thomas Was Alone and John Wick Hex - must have enjoyed the experience, because here he is with his own twist on solitaire-with-a-story, The Solitaire Conspiracy, as part of his Shorts series of smaller-scale projects. It's out now for PC and Mac on Steam and the Epic store.

Now, two of my favourite time-wasters of the last decade have been Birkett's delightful, Jane Austen-inspired amuse-bouche Regency Solitaire and Klei Entertainment's mini-masterpiece of future espionage tactics, Invisible, Inc. The Solitaire Conspiracy appears strongly influenced by both, so I was excited to try it. Like the Klei game, it features a cast of augmented spooks and hackers on daring undercover missions, and has a sharp-edged, neon-lit aesthetic, all violet and cyan over midnight blue and suspenseful synth music. Like Regency Solitaire, it playfully - perhaps arbitrarily - frames a ripping yarn around hands of solitaire, where the aim is to clear a layout of cards to progress to the next chapter.

Both comparisons are unfortunate ones for The Solitaire Conspiracy. Invisible, Inc. found, in a procedurally generated, XCOM-style turn-based tactics game, a perfect engine for creating knife-edge stealth scenarios for its cartoon espionage action. Bithell tries to find a similar thematic sympathy in solitaire, envisioning the cards as unruly agents, the suits as spy teams of contrasting styles, and the player as spymaster, brooding over the field of play and trying to bring order to the chaos.

It doesn't work. Solitaire can be absorbing, but it isn't dramatic.The dynamic music that builds to a crescendo as you clear the last few cards of each hand just sounds silly. (Yes, dynamic music: for a humble solitaire game, The Solitaire Conspiracy is lavishly produced to the point of absurdity.) Birkett understands this, which is why Regency Solitaire delights in its own blithe inconsequentiality - and why its more ambitious and adventurous successors, Shadowhand and Ancient Enemy, layer role-playing game systems on top to deliver the conflict and drama, while the card-clearing mechanics of solitaire become the dice-rolls that power the adventure, rather than the adventure itself.

And where Birkett takes a classic style of solitaire - essentially Tri Peaks - and enlivens it with elaborate layouts and arcadey mechanics like combos and power-ups, Bithell has tried to redesign the game itself. This is something you should only attempt if you are Zach Gage (and maybe not even then). Solitaire doesn't really fit into normal schools of game design. It is a puzzle and a game of chance at the same time, which ought to be a contradiction. If you try to fix its essential cruelty or its illogic, you break its spell.

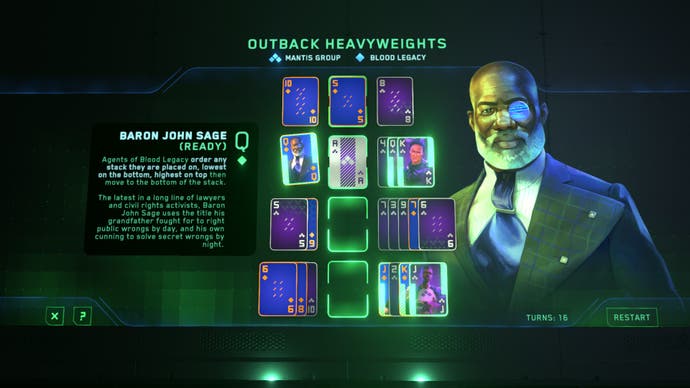

Bithell's version of solitaire is pretty simple: you build the suits on foundations by moving cards around, placing them only on cards of higher value, until you can expose the cards you need in the stacks. The twist is that the Jack, Queen and King of each suit can be placed anywhere, at which point they activate a power that may be helpful (sending the next card in the suit it is placed on to the foundation, wherever that card may be) or unhelpful (reordering the stack from high value to low) or could go either way (randomly scrambling the stack). There are quite a few suits, each representing a spy team, from rogue AIs to Fast & Furious style getaway experts.

The choice to have many of the powers hinder rather than aid your progress is baffling, since these are all supposed to be your own agents, not the enemy's. I guess it's intended to represent the delicacy with which unpredictable agents need to be handled in the field? It is not at all satisfying to play, though - this is a game in which you expend a lot of your energy trying not to use the mechanics, rather than exploiting them in clever ways. You soon realise the most pedestrian way to solve the decks is usually the best. That doesn't make you feel like a cool spymaster.

I'm not going to make the mistake of taking The Solitaire Conspiracy's storyline too seriously; it's clearly just a bit of fun, going by the over-the-top cyberpunk mission scenarios, while gaming personalities Greg Miller and Inel Tomlinson are miscast but still likeable as untrustworthy fellow spymasters. (I'd love to see a game capture Tomlinson's irrepressible hype-man energy, but this isn't it.)

I take solitaire very seriously, though, and The Solitaire Conspiracy left me feeling that Bithell hadn't succeeded in pinning down the game's profound but elusive draw. It is not a game of strategy or control; it isn't you and it isn't your enemy. It's the space between you where stuff goes down (as Birkett correctly imagines in the solitaire combat system of Shadowhand and Ancient Enemy, which, if it isn't clear by now, I strongly recommend you buy instead). Solitaire is life, it's luck, it's shit that happens. You don't win it. You make sense of it, clear the table and move on.