Kentucky Route Zero's magical realism hides the raw economic realities of abandoned towns

There are no two ways about it.

A while back, the BBC did a series on the trains that travel across the hills of India. These were services built during British rule, engines still humming along thanks to sheer determination. The last episode visited Shimla, the summer capital of British India, including the Chapslee Estate. It had turned into a small hotel, where the now-deceased Kanwar Singh spoke fondly of its charms. He described his services not as a business selling accommodation or food, but selling an "ambience" of a previous age.

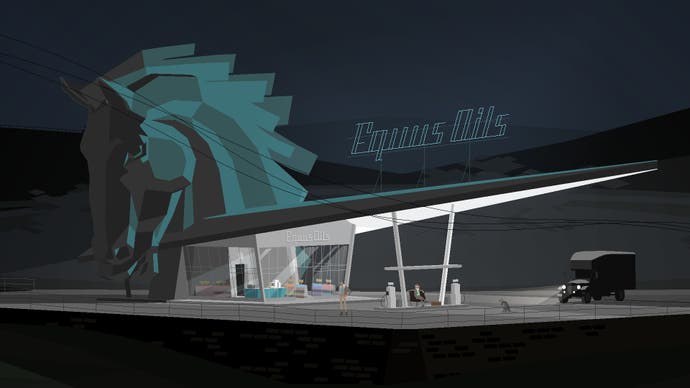

Kentucky Route Zero, a point-and-click adventure that was a decade in the making and that released its final episode in January this year, seems to provide a similar type of ambience, one not based explicitly in time. The story follows Conway, an antiques delivery driver making his final stop, searching for the mysterious eponymous highway in a world drenched with magical-realism.

You might have conjured up images of hillbillies and farming knowing the game is based in Kentucky. But this couldn't be further from the truth, with designer Jake Elliot, along with Tamas Kemenczy and musician Ben Babbitt, speaking of diverse literature, plays and films, such as the work of Andrei Tarkovsky, all of which provided sources of creative inspiration. "We have a story of somebody making a delivery," Elliot says during a group video call with me, Kemenczy and Babbitt, "But of course it's run through with the emotional realities of why they're doing it and what it means for them. That's how I'd experience it."

To me, this simple explanation demonstrates why the game has been so successful, inviting us not only to follow this austere story, but to begin to explore the world behind these characters and their actions. KRZ reminded me of David Lynch's The Straight Story and Alexander Payne's Nebraska, two films that also take place in "middle America" and, a coincidence pointed out to me by Kemenczy, involve older men on road trips. While The Straight Story feels heavy-hearted and wistful, Nebraska shows some of the demographic declines small towns face, with very few characters under the age of 35 even visible throughout the film.

This isn't to say KRZ and these films create an artistically interesting "Midwest Shitfest", but that the underlying economical and political reality these small towns and cities face are very recognisable, even to someone from the north of England like me. As a concrete example, my hometown has seen all five local bank branches disappear in recent years. Heck, this story featuring a non-functioning gas station in West Virginia reminded me of the opening scenes in KRZ at the time it was published. It's surprising how few creative pieces of work, games or other forms, have tried tackling these themes.

"It seems kind of necessary to be able to react to things in real time, and for a project to accommodate new and unforeseen interests or lines of inquiry," said Babbitt, in response to a question about themes of climate change and environmentalism being more significant in the game's later episodes. What's brilliant about KRZ is how almost everything here is subtext and hidden under the dialogue of its witty characters. This has made its universe incredibly dense and varied, with the designers releasing strange yet fascinating game-to-live-action videos over the years and even making one of the game's interludes available as a paperback.

This evolution of opinion behind the scenes is recognisable after watching the non-narrative documentary film Baraka and its sequel Samsara, which I've mentioned previously. I was intrigued by how palpable and obvious the anger lies behind the camera between the two films. Whereas Baraka is a wide-eyed fascination at the magical diversity of the world we live in, Samsara captures the environmental destruction and capitalist consumption driving us and the planet down to inevitable catastrophe.

Some of this was also the aim of KRZ, as Elliot describes the partial truth of people in small towns being "left behind and abandoned", and that places like Kentucky were treated "almost like a colony" regarding their historical exploitation for coal and saltpeter. He also describes the way the people were exploited, "When these companies go bankrupt, they no longer have to pay into these funds for the miners' long-term healthcare and pensions. They totally abdicated responsibility."

It's this abandoned, underground world where KRZ conjures up feelings of confusion and terror about what the "modern" world really is and who it serves, while dismissing the idea that people who live in rural areas are inherently "stuck" in the past. However, this sense of abandonment is something that's following people earlier in life now. "Places like Chicago are getting prohibitively expensive and forcing people to move out of urban areas," says Kemenczy, who still lives in the city but is witnessing the continuous population decline since its 1950s peak.

In one recent political rant with my parents, I was discussing how this was happening in the UK too. The trend started in 2010, with the country's older, property-owning generations now continuing to inflict unbearable pain on those younger than them through general elections. Housing costs continue to spiral and, in real terms, wages have been stagnant for decades. Richard Farnsworth's character in the Straight Story describes how "the worst part about being old is remembering when you were young." It's with this dose of reality that KRZ's journey ends. The characters ask themselves and each other whether it's worth staying behind to rebuild a community.

That choice almost acts like the fulcrum for the way in which we're able to act out our politics in the game. The recent pandemic has exacerbated so many social and economic issues, with many people realising that, yes, wow, money does indeed alleviate all kinds of issues we experience. Even Australia is going to face this reality. But what KRZ does so wonderfully well is to mesh the personal and economic problems for all of these characters through an intricate world. It may seem apparent and obvious by now, but the game is simply reflecting complexities of our own world. The conclusion to this is that we become glowing, debt-ridden skeletons serving corporate needs like those featured in KRZ's underground caves. I'd rather we become the characters living on the surface, conjuring up memories of a life well lived.