Whatever happened to City of Metronome, the missing game by Little Nightmares developer Tarsier?

"You change."

Downtown Los Angeles, 2005. A hot, bloated, extravagant E3, and everyone more excited than normal because it's new-console year. PlayStation 3, Xbox 360 and Revolution (Wii) are all at the show, and anything labelled "next-gen" is stampeded. Perhaps that's how a group of Swedish students, with no publisher and no track record, manage to entice people to see their game.

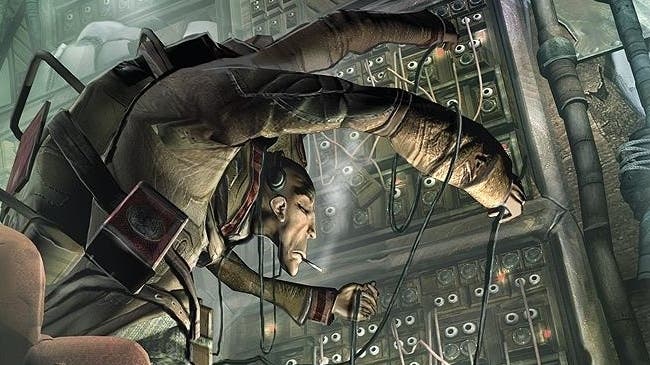

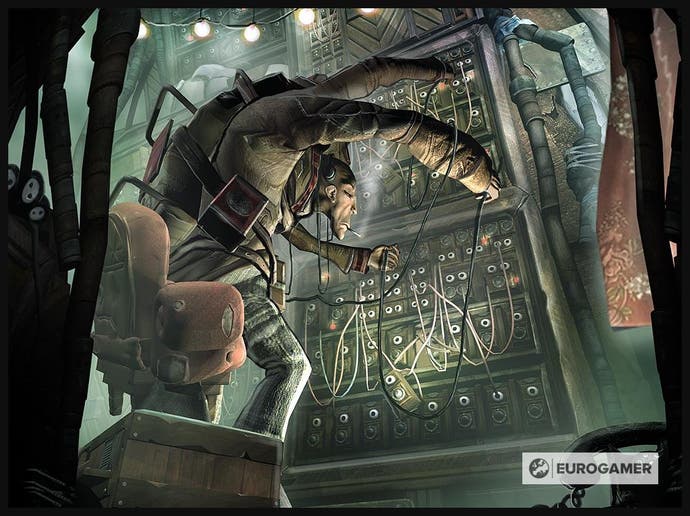

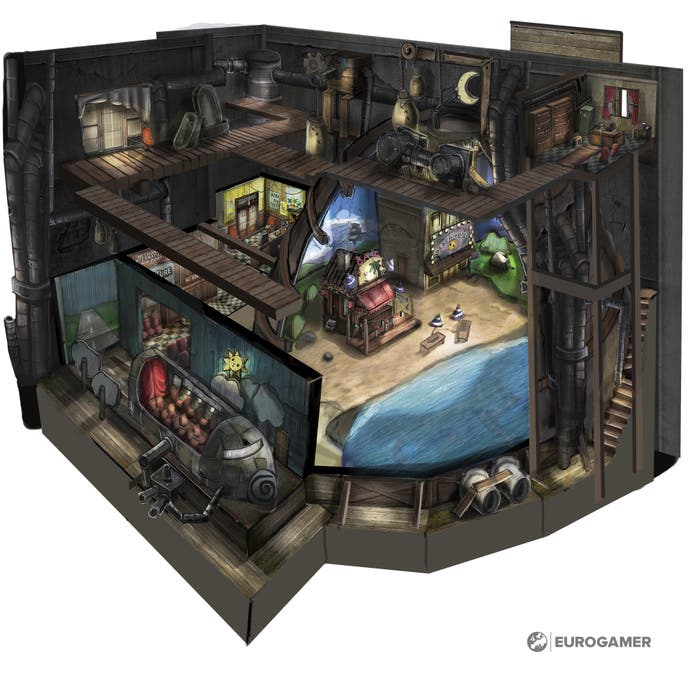

But, there is something exciting about what they're doing. Their game is different, darker, and more off-beat than mainstream games usually are. It's set in a dark city of warped rooftops and gnarled horizons, a place run by a malicious Corporation and its mysterious world-building machine, powered, it seems, by the souls of children. Children sent back out to work in the city as mindless zombies dubbed metrognomes.

You play a young steam-train engineer's apprentice, whose routine obedience is challenged the day he meets a girl on one of his trains. She questions the world around her and begins to make you question it too. She opens your eyes. Together you'll uncover the truth of this city, the City of Metronome.

There's something in how the game plays, too. It doesn't have traditional combat. Instead it uses sound. With a kind of backpack and attached listening tube, you can record the world around you and then replay sounds to various effect. You can solve puzzles with them, like voice-activated locks. You can send enemies scurrying away with loud sounds. And you can use music to soothe the sad children, who will do things for you in return. Need a heavy block moving? No problem. Need someone to throw themselves into the cogs of a giant machine to bring it grinding to a halt? You're a monster, but yes, they will.

That was City of Metronome, dark and moody and memorable, and by the looks of the playable demo, well on the way to becoming a full game. After E3, we waited eagerly to hear more. But a year later, nothing, and a year after that, nothing too. We waited and we waited but City of Metronome faded away.

What happened to it? That's what I am trying to find out. That's what I have gathered Tarsier Studios founders Andreas Johnsson and Björn Sunesson to discover (narrative designer Dave Mervik also joins us, who you might remember from my Little Nightmares 2 interview, though he didn't join Tarsier until later.)

And the most important thing to know upfront is back then, which was a long time ago now, they didn't know what they were doing. Metronome was their first game. Really, it was their coursework, paid for by their student loans. And pitching it at E3 was the culmination of their work and the end of their course. After that, they'd be on their own. They were, in a sense, pitching for their future.

The thing about demo pitches like this is they're not full games. They are a collection of exciting ideas intended to excite people about what can be made. They have not had to face the hard realities of being finished. City of Metronome was ambition. And, more than that, it was young, naive ambition. It was a combination of ideas from nine students who wanted to change the game-making world.

"There was no one who had this exact vision of what stuff should be," says Björn Sunesson. "We were just fuelled a bit by naivety. What if we can create something that has the coolest gameplay and the best world and [a] super-good story? And obviously we had no idea how to do those things."

Really, that's where the problems started. Even now, they can't tell me what the original pitch was, which is alarming really, given they travelled to E3 to do exactly that, pitch it. In fact when I ask about their pitch, they start laughing. CEO Andreas Johnsson cracks up.

"I'm laughing," he explains, "because when we worked on the game and we were about to reveal it [...] we had this video, and we wanted to kind of make an impact. And I think that's when I wrote that really shitty line that no one liked."

There are titters of recognition from Sunesson, but Dave Mervik doesn't know what they're talking about. "I don't think I've ever heard this! Go on," he says, "say it! Say it in the voice as well."

So Johannson does, the style of a cinematic trailer voiceover. "A next-gen action adventure game where sound is your weapon," he says.

"That was you?!" blurts Mervik. "How did you end up CEO?!" And at this they laugh so hard Johnsson sounds like he's crying.

It's as close to a game-pitch as I can get from them, and yet, the tagline worked. "No one had ever heard of us before and all of a sudden, we had the whole week booked," Johnsson says. "That, for me, was a clear signal we were onto something."

They were, as he delicately puts it, "complete noobs" at showing it. "We did a really shitty job presenting the game because we had never done it before. We were super nervous - I was super nervous at least. And we had all these meetings with Sony and Microsoft - I can't remember - all the different publishers that we'd never met before." Someone actually recorded off-screen camera footage of the Metronome presentation, if you're curious.

"I mean, maybe it was terrible," Sunesson adds. "It might have been a bit charming, though, because we were excited about it and enthusiastic, and even if the presentation was shit, the stuff we showed was cool and different."

It certainly was. What people saw stirred something in them. They saw barefoot urchins with bent top hats and radishy noses, and sack-headed robots guarding crime scenes with clubs in their hands. They saw smoggy purple skylines, where factories tangled with skyscrapers, and beneath them a warren of gantries and crooked staircases and strange machinery churning in basements.

Once you saw Metronome, it was hard to forget it. People likened it to films such as Dark City and The City of Lost Children, which was high praise, and as word got around, a buzz started to form. The team which would become Tarsier Studios left E3 on a high. "We got home thinking that okay, this is going to be good," Johnsson says.

But then - and this might sound familiar - nothing. No phone calls, no publishers offering to fulfil Tarsier's dreams. No nothing. "I mean, we did have some discussions..." But they weren't noteworthy enough to talk about. It wasn't until a couple of months later, at Gamescom, they finally made some progress in the shape of Sony. "They picked up on it instantly," Johnsson says. "And then we started those more concrete discussions with them."

Great!

"But that also ended up falling flat."

Not so great.

"We couldn't deliver on what they needed in order for us to get funding," he adds. "That could be a mix of uncertainties: the team is not experienced enough compared to the size of the game, some holes in the concept - things like that."

But there was a silver lining: an important relationship formed. Sony liked Tarsier, and when Media Molecule was looking around for someone to port Rag Doll Kung Fu to PS3 (this was a long time ago, before LittleBigPlanet), Tarsier got the job. The rest is history: Tarsier worked with Media Molecule for many years to come.

"I don't think it's correct to say that publishers were chickens who didn't dare to do it..."

-Björn Sunesson

Tarsier hadn't given up on City of Metronome, though. A second demo was built, using some prize money from a contest, but it was never shared outside of the company. "We never felt that it was something that we could take, or wanted to take, further," Johnsson says.

Then, in 2008 or 2009 - a long time after the initial E3 unveiling - Tarsier assembled a group of design leads, from LittleBigPlanet Vita and Little Nightmares, for a kind of City of Metronome summit. "Hey, can you guys figure out this thing that we're not smart enough to do?" they were asked.

There was a problem Tarsier kept running into with Metronome, you see, and frustratingly it was a fundamental problem. It had to do with the sound-recording mechanic in the game, the one that had caught so many people's eyes. Very simply, they couldn't make it much fun to play.

Björn Sunesson explains: "This idea that you're trying to use sound for something instead of other types of actions: it always has to be cooler than doing the other type of actions, right?

"If you want to make a weapon out of it and essentially it functions as a shotgun, but then, 'Oh, it's sound,' it's just like a lamer version of a shotgun [...] It's hard to figure out something that makes it worth doing so it doesn't become a gimmick where you dress up a button press."

The assembled people of the summit couldn't work it out either, so, that's really where City of Metronome stops ticking. This mishmash of exciting ideas nine students threw together years before had proved too difficult to fulfil. Even with publisher funding, there's a huge question mark over whether the game could have been made.

"I was convinced back then that we could do it," Sunesson says. "Now, I think that maybe we could have done it back then, but I don't think we could have done it now, if that makes sense?"

Actually, it does. Back then, they had ignorance on their side. "Yeah," Sunesson continues. "At some point you start trying to adjust things to reality and then being disappointed with what it ends up with being, or pushing it in some weird direction. You have a bit more courage when you don't know what you're doing. I feel like we could have finished it, but I don't know if we would have survived mentally.

"I don't think it's correct to say that publishers were chickens who didn't dare to do it, because it didn't make any sense from a money point of view to do it."

Sunesson then asks what Johnsson thinks.

"If we could have made it?" Johnsson responds, pausing to think. "I'm quite happy how it all ended up, working with Sony and Rag Doll Kung Fu. If we would have gotten the chance to take it on, maybe we could have done it, but it would probably have put a lot more... [and the unsaid words here seem to be 'pressure on us']. Would we survive that?

"I think if we had started doing it, we would have ended up cutting the sound-based gameplay and done something that's more traditional."

If they did, would it still be the City of Metronome we were after? It's these kinds of imagined expectations that still give Johnsson pause today, whenever he considers a possible Metronome revival. The idea is not dead you see, it bubbles up every now and then. 'Should we do something?' he will wonder. 'Should we explore the word and see what we can do?' "It does pop up every now and then, every other year or so, like, 'OK, hmm, what if?'"

What excites them is the idea of roaming, freely, around a city like Metronome's. That's something they haven't done in a game yet. "Wouldn't it be super-exciting to be able to go wherever you want in that city you see in Little Nightmares 2?" asks Dave Mevik, thinking out loud. "If you just wander around some fucked up city, that kind of thing is really exciting, worldwise."

"But there is a time and place for everything," Johnsson adds, "and maybe it is dated."

Sunesson seems to agree. "Some things are very dated," he says. "Not just from, like, 'What is the zeitgeist right now?' But also from who we were then and what are people interested in doing now? You change. But I wouldn't rule out that we build something in a really cool city that you get to explore and dig into, and have some gameplay. But I don't think that would be the City of Metronome city."

I'm sorry to dash any hopes you had of a revival but it sounds like the door is all-but closed on it. But that's OK, I think, because in some ways City of Metronome did exactly what those fresh-faced students set out to do with it, all those years ago: make a name for themselves. It might not have ended the way they expected, but look where they are now. They've survived for 16 years, and only recently they released the second game in their well-received original series, Little Nightmares. They would never have predicted that back then.

And Metronome never really died. It is, as Johnsson points out, "part of our DNA". You can see traces of it in all of the studio's work. Little Nightmares is dark and warped and eerie, and a thematic continuation of Metronome if ever I saw one. So perhaps Metronome is better left in our memories, where it can live excitedly without restraint. It's not as though Tarsier has run out of ideas: it's currently working on new concepts and I genuinely can't wait to see what they turn out to be. Perhaps some things, then, are better left in the past.