What does gaming's all-digital future mean for the climate crisis?

Part two.

In part one, we talked about companies. Companies - including some of the big players in video games - are improving the efficiency of their data centres, their data transmission, and their content delivery networks. But whether they're doing this fast enough is debatable, varying quite a bit from one company to the next.

They're also improving the carbon emissions directly, by "decarbonising" - sourcing renewable energy - for those data centres and services. But again, whether they're aiming high enough, or acting fast enough, or using the right methods, depends from one company to the next. Even governments - perhaps unsurprisingly - are struggling to act fast enough in decarbonising their national grids. The UK's carbon budget, for instance - the amount of emissions it can emit before surpassing the hard recommendations of the IPCC - actually runs out at the end of 2024, in just three years.

In other words, we have to keep the pressure up on governments and companies - but we also have to think about what we can do ourselves, because while we can't, directly, decarbonise the national grid, or triple the efficiency of a server, or set up a wind farm next to a data centre, we can think about what our choices do to affect the demand for that energy itself.

The question for us, then, is this: what's the least carbon intensive way to play games?

Discs, downloads, or the cloud: choosing how we play

For console and PC players, we basically have a choice of three options for playing games: buying a physical disc, installing a digital download, or more recently, streaming a game via the cloud. There have been a few - although crucially, not many - attempts at answering which one of those three is better. Polygon looked at the environmental case for choosing disc or digital gaming back in 2015, but things have naturally changed a lot since then. And last year, in a piece titled "Why cloud gaming could be a big problem for the climate", Polygon cited a study by Matthew Marsden et al., which looked at several possible scenarios for the future of gaming in 2030, relating to cloud gaming specifically: one where cloud gaming stays niche, similar to how it currently is; one where it grows moderately to become a "hybrid" model of some cloud gaming, some as it is now; and one where it becomes the dominant form of gaming overall.

The results here were pretty bleak: according to the study, the "hybrid" future resulted in a 29.9 percent increase in emissions compared to the current situation, and the cloud-dominant future a 112 percent increase. As the authors concluded: "If streaming at 4K resolution becomes widespread, then it may well be game over."

But this isn't the whole story. As George Kamiya put it to us, "There is always a counterfactual." Naturally, there's only so much that can be taken into account in a single study, but speaking generally about the question, Kamiya suggests a number of examples of what you might need to bear in mind. "I think you could try to understand the footprint of cloud gaming, and then try and compare it to: what if we didn't have this? What would the alternative be? And what would the impacts of those be? You would have to then start to include transportation of the disc, manufacturing of the disc, all those materials, and then the commute for the person as well, [or] if you have it shipped to your house. If you have to go and pick it up, you're using a car - the impacts are going to be quite high compared to downloading even a hundred gigabytes. There's just so many uncertainties and sensitivities."

"There is a straightforward answer to the question 'which method of gameplay has the lowest carbon footprint', which is, 'it depends'."

Dr. Joshua Aslan, in his 2020 study into the climate change implications of gaming.

There has, in fact, been one study into exactly that, and notably it was commissioned by Sony. Authored by Joshua Aslan, initially as a PhD thesis, the study was written under the guidance of several other researchers, including Dr. Kieren Mayers, who is head of environment and technology compliance at Sony Interactive Entertainment, and other renowned experts Dr Jacquetta Lee and Professors Chris France, Richard Murphy, and Jonathan Koomey.

In the 369-page study, titled Climate Change Implications of Gaming Products and Services, Aslan undertakes a full life-cycle assessment of the climate impact of different console-based gaming methods. In other words, taking everything into account from the emissions of a console's manufacturing, to the shipping of the discs, and the average game's development, it looks at which method of gaming - on PlayStation services specifically - leads to the greatest impact on the climate: via disc, digital download, or cloud gaming via Sony's PSNow.

There are lots of important caveats. With the research beginning in 2015 and then being published in early 2020, for instance, it's worth noting the data used is primarily based on the state of things in 2017-2019, which will have already developed further (broadly speaking, that'll likely mean larger average game files, different average playtimes, more efficient data centre and transmission technology, and slightly greener grids), and again worth noting that it was based on UK and European data. Things will vary quite dramatically depending on factors like the mix of energy on your own local grid. The main conclusions are primarily based on using reasonable averages for a lot of the other variables involved, like average game size or play time. There are plenty more, of course - you can read up on the full range of variables in the report itself.

In Aslan's words: "There is a straightforward answer to the question 'which method of gameplay has the lowest carbon footprint', which is, 'it depends'. It depends on the length of time the game is played for, it depends on the file size of the game being played, and for cloud gaming, it depends also on the type of device the game is played on."

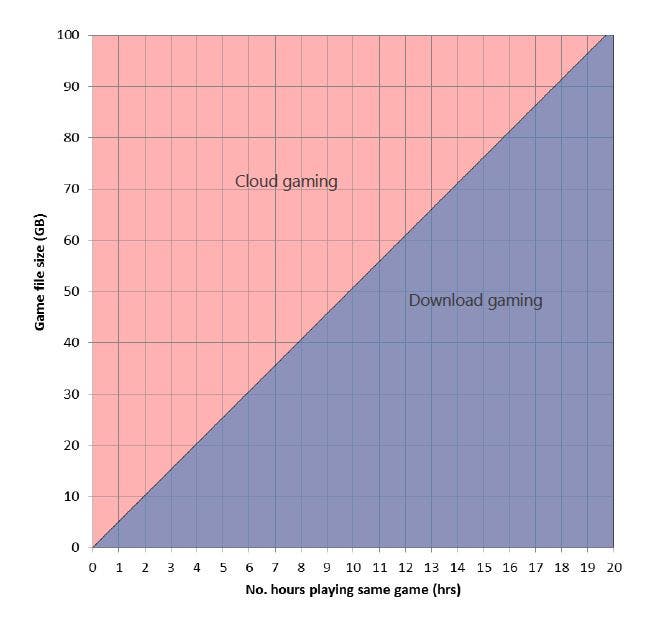

Illustrating this trade-off, as Aslan notes, isn't easy, because there are more than just the two variables. One thing is clear: essentially, buying a physical disc is almost never the most carbon-efficient way to play video games on a console (there's just one very specific case, of a 128GB game played for around 30 to 34 hours, which can be found in Figure 68 pages 250-251, if you're interested). With the choice between cloud and digital, however, it's less definitive. The larger the file size, the less efficient a digital download becomes, compared to playing it via the cloud; but, the longer you play it for, the less efficient cloud-gaming becomes. The result is the aforementioned trade-off, which is best illustrated by this chart, from Aslan's study.

To use the chart, pick a game and decide how long you think you'll be playing it for in total (Aslan for instance uses the crowdsourced numbers of howlongtobeat for average playtimes), then look up the game's size in GB and cross reference it with the playtime. To take an example: God of War (2018) has an install size of around 45GB on PS4, so track that up the y axis to halfway between the 40 and 50 marks, then go across to where the red meets the blue, which is around 9 hours. That, according to the report, is how long you can play God of War for via PSNow before it becomes more efficient, in terms of CO2e emissions, to have digitally downloaded it instead. (Again, it's worth noting that there are a huge number of variables at play here - bandwidth, for instance, impacts things significantly. Aslan accounts for this in the sensitivity analysis on pages 220-240 of the paper. You also have to include the total of all the update files downloaded for that game, too).

It might help to think of it as being like the dilemma of whether to turn off your car's engine at a set of traffic lights. Starting a typical petrol car uses a chunk of fuel in one quick hit, while keeping it running uses a smaller amount, over time. Whether it's better for the environment to turn off your engine while you're stopped at the lights and then restart it when you get moving, or to just keep it running the whole time, depends on how long you're stopped for (as well as the car itself). The same goes for downloading a game: very generally speaking, if you're not stopping your car for long, better to just keep the engine running; likewise, if you're not playing a (large) game for long, better to just play it via the cloud.

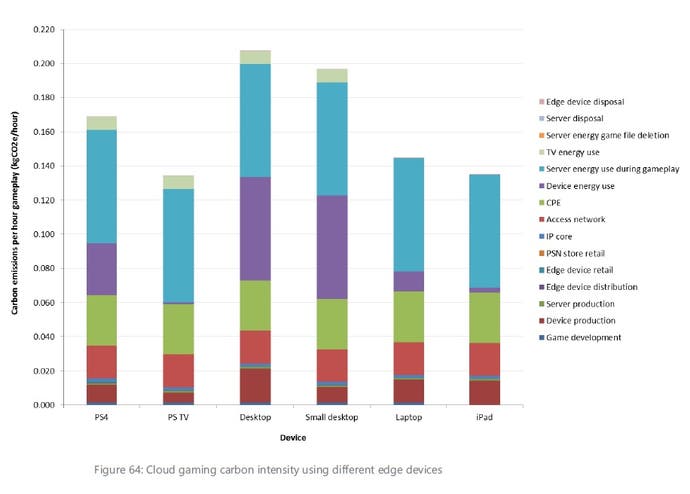

Things change again when you're looking at the platform (or "edge device" in climate researcher terms) that you use to cloud stream the game in question.

All other factors being equal, using the oft-forgotten PS TV to stream games is the most efficient, in terms of CO2e produced per hour, of those studied above. More or less the same is an iPad - the slight increase in device energy use cancelled out by the lack of need for a TV screen to be on at the same time. An average laptop is a little higher, and a PS4 notably higher than this. Least efficient, by some way, is using a small or regular desktop PC, with the emissions from the PC's own energy usage matching that of the energy used in the cloud server itself.

An obvious question arises here. As the chart shows, the main factor in determining which device is best is that device's own power usage. So, why do some devices use so much energy to stream games, when all the hard work should, in theory, be getting done elsewhere?

Consoles, PCs, and "thin" clients: choosing where we play

Dr. Evan Mills is an affiliate, and now recently retired, senior scientist at the US Department of Energy's Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, and a member of the international body of scientists who worked on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change itself, the members of which collectively sharing a Nobel Peace Prize in 2007 "for their efforts to build up and disseminate greater knowledge about man-made climate change, and to lay the foundations for the measures that are needed to counteract such change." Alongside the more than 300 articles he's published on the topic of climate change, he's also created a website about gaming.

Greening the Beast is a site based on Dr. Mills' 2015 study, co-authored with Nathaniel Mills, titled "Taming the energy use of gaming computers". The site's described as a project "dedicated to helping the gaming community green up its act, while improving performance, lowering temps, and saving a few bucks," and features a variety of tips for building and running more efficient gaming PCs.

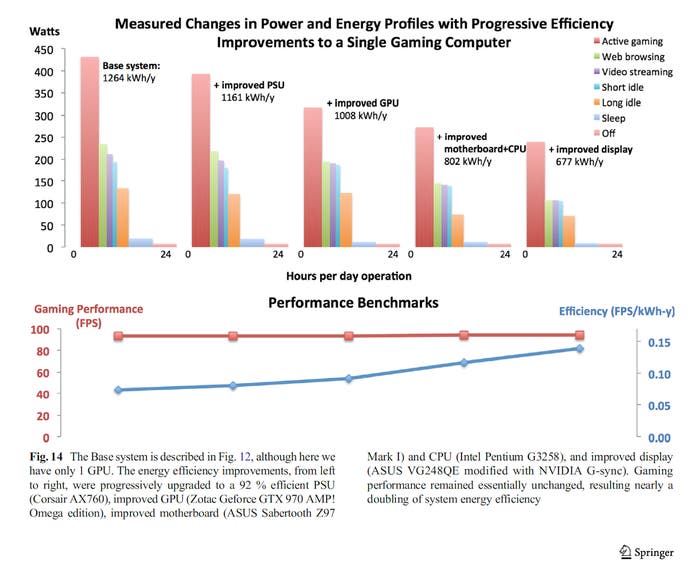

The original study is all about those PCs, specifically citing the huge amounts of energy usage that can be saved without impacting performance. "More than 75 percent" of a given PC's energy could be saved, "via premium efficiency components applied at the time of manufacture or via retrofit," the study claims, all "while improving reliability and performance." It's a whole other problem, in a way. Even when taking cloud gaming out of the equation, the average desktop gaming PC is simply not anywhere near as energy efficient as it could be - or ought to be.

More on that later. Right now, cloud gaming is in the equation, and the energy intensity of it when playing on a PC or certain consoles is an issue, if nothing changes. Speaking to Eurogamer via email, Dr. Evan Mills explained the problem.

"Some of the local energy use is unavoidable (e.g. running the display and processing needed to deal with the cloud data transactions), but clearly there is a lot of bloat in this. As you'll see in the reports, some systems use as much or almost as much energy when they're in idle mode as when in full-on gaming mode (fig 22, page 43 in this report, which I'll call "the main report").

"We refer to this as a lack of 'system integration'. There is also a lot of unexplained variation in energy demand during standby AND significant fluctuations when workload is not changing at all (see Fig 20, page 40 in the main report ). The high-end Digital Storm system we looked at in the report does this superbly, using up to 30 percent less energy (and arguably achieving a superior user experience) than mid-range systems that are clearly klutzy (Table 8, page 91 in the main report).

"If people gamed on thinner clients connected to the cloud it would help, but, still, it means everyone is gaming on the most powerful GPUs plus all the energy to cool and ventilate the data centers, plus the energy to move the info through the internet."

As far as the "what can we do?" question goes, this is the crux of it. It matters where you're gaming as much as how you do it. As per Mills' original report, for instance, playing Skyrim on a Nintendo Switch uses just a twentieth of the power of playing it on a custom-built, high-end gaming PC. "We see no correlation between energy use and frame rate across actual products and games out there. This suggests that the industry isn't doing a good job at optimizing energy use," Mills wrote. "One has to ask whether playing Skyrim on a Nintendo Switch with 1/20th the energy is only 1/20th as fun as on a souped-up desktop."

You can view the full rundown of systems, which goes from the PS3 and Xbox 360 generation up to the PS4 Pro and Xbox One S, in Mills' original report and a follow up published in 2019 (figures 4a and 4b). The long and short of it is, generally, portable devices like the Switch or Nvidia Shield use by far the least energy, and more typically "powerful" ones like the PS4 Pro, original Xbox One, and high-end desktops use disproportionately more. Even if you do play games on a desktop PC, the components used to build it make a quite dramatic difference. The problem is, compared to just about every other household appliance, gaming devices of all kinds just don't really emphasise efficiency, compared to raw power and performance.

Priorities, preferences, and externalities: changing how we think

At the time of writing, the newest generation of consoles - the PlayStation 5 and Xbox Series X - use even more power than the previous generation. To an extent this is natural for consoles. Generally, consoles tend to "spike" in consumption at the beginning of each generation's cycle, progressively decreasing with software and hardware updates as the years go by. (Worth noting too is Microsoft, Sony, and Nintendo are also all signed up to the Voluntary Agreement which, in brief, is a pact based on EU directives that sets absolute limits on console power usage during different activities, and introduces rules on things like how long a console can be left idle before it must automatically power down. You can view the full extent of the rules in the latest version.)

Console power consumption changes through recent generations

| Console | Dashboard Power Consumption | Selected In-game Power Consumption |

|---|---|---|

| PS4 (launch model CUH-1016A) | 83.7W | 137.3W |

| PS4 Pro (launch model 70XX) | 60.4W | 126.1W |

| PS5 Disc (launch model CFI-1016A) | 43.1W | 196.9W |

| Xbox One | 48W | 110W (Gears of War 4) |

| Xbox One S | 22.5W | 73W (30fps) |

| Xbox Series S | 25W | 82.5W |

| Xbox Series X | 42W | 210W |

Note: PlayStation figures based on 3-game average of PS4/PS5 games for the relative consoles, source: Playstation.com. Xbox figures are based on Gears 5 (peak) figures, source: Digital Foundry (base Xbox One here). PlayStation models chosen are the launch models; Xbox consoles are Digital Foundry test consoles.

At the same time, this poses a further question, which is potentially the most important of all: how do we change not only what we use, but how we think about that usage? When speaking to Dr. Mills, we asked him what he, as an expert, would suggest asking the major platform-holders, like Microsoft or Sony, were they to respond to Eurogamer's requests. He suggested three things.

One was technical: what's the status of data centre providers being able to support multiple simultaneous users on a single GPU? (This is, by the way, a key technological hurdle companies are trying to get over, as each doubling of users cuts GPU energy use in half, potentially providing a big leap in data centre efficiency. It's a shame we weren't able to ask them how progress was going.)

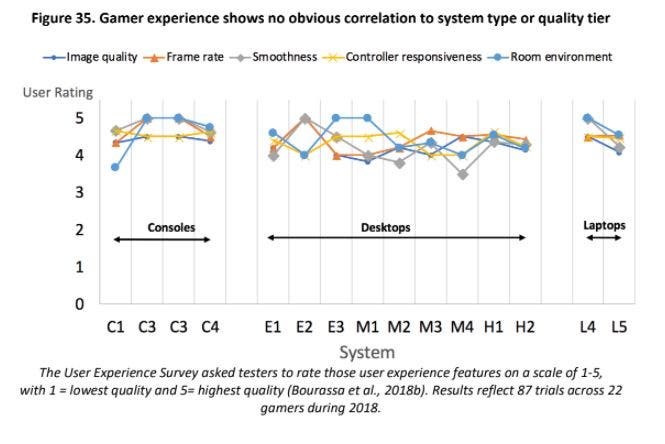

The other two were more philosophical. "Ask why the latest gen consoles had to use more energy (in an absolute sense; don't get sidetracked with rhetoric about efficiencies) than previous gen," he said. And, related to that: "Ask what the human/biological limits are to the value of ever-increasing 'performance'. The gamers we interviewed after doing blind tests of different systems in controlled conditions in our lab couldn't really discern among the systems, i.e., they had as much fun gaming on less energy-intensive [systems] (in some cases meaning lower frame rates, etc.) than high-end ones (page 58, fig 35 in the main report)."

This echoes something George Kamiya also mentioned during our conversation. He suggested there's more to the issue than just the immediate carbon footprint alone. "What I sometimes worry about is that there's too much focus on the footprint and not enough on the effects that it has on society, and in other sectors - both positive and negative uses," he said.

"So there's a lot of hype from companies to say, 'Oh, our AI, or digital technologies, can reduce emissions in agriculture, or in transportation by using smart logistics.' But they often don't talk about the negative effects - that maybe it's making fossil fuels more competitive, because you can use machine learning to extract oil cheaper, or extend the lifetime of a coal plant, or something. I think we're in this phase where it's easiest to understand and track the energy - I mean, it is already hard to understand the energy use of gaming or Netflix or any part of digital's direct footprint. But the kind of systemic effects on society are much, much harder.

"Sometimes that kind of holistic picture is missing. I guess for gaming, there are these kind of 'rebound' effects. [Increased efficiency or accessibility] induces more demand, typically, so you might get more users or bigger files, because the incentives aren't aligned. It's kind of this runaway effect - and then you'd have the hardware providers [saying], 'We need to develop more powerful GPUs,' or, 'We're going to market our GPUs to sell every year and you should refresh your computer, because now it's too slow to run the latest game.'

"I think there are these kind of knock-on effects that we should also be talking about, because it's not just a story about the electricity you use at the plug, right? It's the materials and energy use that goes into producing that GPU, or the data centre, or your screen. And that's going to get proportionally higher over time, as these data centre operators decarbonise, and as our grid decarbonises. So even if you lived in Norway, where your electricity is basically zero carbon or close to it, if you ran a super powerful PC, and you had a huge screen at your house, the carbon emissions are very low - but there was a lot of carbon that went into producing your computer and your screen. That's obviously much harder for the consumer to control, other than to buy less frequently or to have more repairable or upgradable components."

"Sometimes, that holistic picture is missing... it's not just a story about the electricity you use at the plug."

George Kamiya, IEA.

The externalities go on and on. On the one hand, working from his console- and location-specific averages and assumptions, Aslan found that "over the average five-year lifetime of a console, a user who only downloads games is estimated to produce 86 kgCO2e, equivalent to the carbon emissions arising from 123 washing machine cycles, or three train journeys from London to Glasgow. This study also shows that gaming has low carbon emissions when compared to other leisure activities. Comparing the results in this study to research by Druckman et al. (2012), gaming has lower emissions than going to watch a movie in the cinema, or playing sports with friends, due to the travel emissions associated with these activities."

In one sense, that's good news! On the surface it generally seems better to play video games at home than to drive somewhere to do something else. But then keep looking at externalities and things might swing back the other way. One more from Kamiya, for instance, was a suggestion that ever-growing gaming downloads would eventually impact network infrastructure itself. "It is actually important to reduce the peak data output," he said, "because a lot of this internet infrastructure, especially on the data transmission side, is built on: what is the peak?" This, if you remember, is exactly what Ofcom was talking about, in part one, when they explained their agreements with gaming companies to shift the times of their downloads. "This is why, during Covid, people were worried. The European Commission was worried that people are going to be streaming Netflix at home, and it's going to cause these outages in the network, but it turns out we were well under capacity because these network providers have already built up based on that kind of 'worst case' peak. But if we can reduce that peak, we can have less equipment running 24/7, which means less energy overall.

"The holy grail has been to find a universal metric of efficiency..."

Dr. Evan Mills, IPCC Scientist.

"So there is a short-run, kind of marginal sense, where if you as a single user scaled back half the data [you consume], you're not going to be saving half the energy. But in the long run, in terms of how these network providers are building out infrastructure, and using energy, that actually does have an important impact on how they decide to build."

To go back to Dr. Mills, "The holy grail," he explained to us, "has been to find a universal metric of efficiency. Normally this is not hard, e.g. liters/100km for cars, kWh/cubic meter-year for fridges, energy per square meter for homes... but for gaming, the 'denominator' is the gaming experience itself (fun), which is not quantifiable! The only way forward I can see is to focus on absolute energy use per system, e.g. energy use per minute of gameplay, as well as in other modes (sleep, idle, browsing...). This also makes sense since we, as a society (including gamers themselves) are facing a climate crisis that requires deep absolute reductions in greenhouse-gas emissions." The word "absolute" is key here: regardless of how big gaming is compared to anything else, if the emissions it produces can be reduced, then they should be reduced.

"A consumer decision-making environment largely devoid of energy information and incentives," to quote Mills' study, "suggests a need for a targeted energy efficiency programs and policies in capturing these benefits."

As is already clear by this point, we haven't had responses to our requests to talk about these kinds of topics with the types of companies that can make a real difference on their end. But even thinking about those questions alone seems important. There are limits to what we can humanly perceive, in terms of maximum frame rates and resolutions at certain distances - and even if there weren't, Mills' studies show the actual returns from those higher frame rates and higher resolutions are diminishing at best.

There is room - and now a necessity - for not just a change in habits but in philosophy. Energy usage can vary dramatically from one game to the next, even those of similar genre and scope, according to Mills' studies, which means even developers and publishers need to think about energy efficiency as a part of development. And likewise, just as we ask ourselves whether a new GPU might be worth it in terms of the financial cost of additional frames per second, we should also be asking ourselves whether those additional frames per second are worth it in terms of the cost to our future on this planet.

A responsibility to care

Slowly, things are changing, and it's important to remember that digital distribution still represents a positive change for our industry. George Kamiya reminds us of the quote by climate researcher Jonathan Koomey, that "it's more efficient to move bits than atoms", meaning it's more efficient to move data than physical things, and he's right. Generally speaking, it's much easier to upgrade an entire data centre than it is to upgrade an entire supply chain.

But the climate emergency is upon us, and it is no longer acceptable for companies to be without a plan for reducing or eliminating their carbon emissions. There isn't time. Nor is there time to wait until 2040 or 2050 to reach their goals. Change needs to happen now, and for this to happen, we need to work together. We need the industry to push aside secrecy and work towards overcoming something bigger, and encouragingly, the green shoots of collaboration are there.

The Playing for the Planet Alliance is a United Nations-facilitated initiative to get the games industry working together and committing to environment-related goals. Some big names are signed up, such as Google Stadia, Microsoft, Sony Interactive Entertainment, Ubisoft, and Unity. There are 19 companies listed in the 2020 report. But there are some notable absentees too, like Epic Games, Nintendo, and Activision Blizzard - companies that run some of the biggest gaming services in the world.

Joining the Alliance means making a commitment to it, and then each year there's an annual report showing how a company has done, and what they've got planned for the year ahead. You can read the 2020 Playing for the Planet Alliance report online. The goals are negotiated company by company, so they vary, which is why some companies can be seen doing more than others.

But companies aren't penalised for doing badly. Badly isn't really even a concept the Alliance recognises. Yes, if companies don't meet their agreed-upon goals, there's "a conversation", as Sam Barratt, co-founder of the Alliance puts it, but no one has ever been kicked out, because it's not that kind of deal. The deal is getting companies around the table to begin with. "Let's get people into the room so they can learn," he says.

"We're very clear that we are facilitating this. We're not judging. We're not telling people what to do. [The United Nations Environment Programme] has no power or control over the judgments that people make. What we're looking to do is empower them with the best tools, a meaningful personal conversation where they can learn from each other and make a difference. And so if they choose to do that, then great."

"Indifference remains a major obstacle."

Dr. Evan Mills, IPCC Scientist.

But if the entry requirements are negotiable, why aren't more companies signed up? Perhaps it's the industry's deep-seated culture of secrecy. "These are naturally NDA-led competitive organisations that aren't used to sharing easily," as Barratt says. "A lot of people say we're not used to working in this way." Or perhaps it's fear of being called out for doing it wrong. "It can be seen as a politicised space," he adds. "What we're really trying to do is get away from that in an effort to simply bring people together." But do we have time to wait for companies to pluck up the courage to take part?

UK games industry trade body UKIE is collaborating with the Playing for the Planet Alliance, and earlier this year published an 18-page Green Games Guide outlining the challenges companies face and how to begin tackling them. "There's a real sense of urgency now," Dan Wood, co-author of the Guide, tells us.

The culmination of this work will be a global Green Games Summit held alongside the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26) in Glasgow this month. The Summit will be open to anyone working in the games industry, globally, and be online and free.

Over the course of two afternoons (20th-21st), environmental experts and gaming experts will share what they've learned before everyone comes together to think about what can be done. As Wood says, "The Guide gets the conversation started, the Summit is the next phase of getting people to actually come together and put some brain time on it."

But it's not just the production and delivery of games that's being looked at. Games offer something else too. They offer the ability to actively share ideas with people and to make them think. Games can reimagine futures, show people the consequences of their actions, and make complicated topics easier to digest. "That's the magic of games," Wood says. And when you factor in all of the mobile markets around the world, there are nearly 3 billion people playing them (according to games market analyser NewZoo).

This is what the Green Game Jam is all about: a way of challenging gaming companies to find ways to make 'green activations' in their games, which could mean adding new maps, modes, themed events, storylines - anything, really.

The winner of this year's Green Game Jam was industrial revolution city-building game Anno 1800, for its ability to react to the player's plundering of natural resources, and respond accordingly, with food supplies destroyed for future generations, or islands deserted because of deforestation. It's this kind of thing the Green Game Jam likes. And when you consider games' preoccupation with beautiful natural worlds, and escapism, it's not hard to see the potential for more to be done.

But the responsibility isn't only on gaming companies to improve. Yes, they bear the brunt of it but we individually have a responsibility too. We have a responsibility to look at the equipment we use, and the power we use, and wonder if we can do better. Perhaps in how we use our games machines, or maybe it's in how often we look to upgrade them. Do we really need to buy a new graphics card every one or two years? "Indifference remains a major obstacle," says Evan Mills. "No one thinks 'their' energy use and emissions matter enough to worry about." But it does. "Gaming matters," he says, particularly if you're playing on PC.

More than that, we have a responsibility to care. We have a responsibility to try and change the conversation from being only about 'more power' to being one that includes efficiency too. There are few, if any, other industries where manufacturers would get away without mentioning this, so let's put the pressure on.

If we don't?

"I would say we have nine years and six months to keep the planet under 1.5 degrees," Sam Barratt says. "The video gaming industry is the most agile industry in the world and knows how to capture imaginations better than anyone else in the world. We only have one planet. Mars isn't habitable, despite what Elon Musk might think. And this is a 'yes, and...', all hands on deck moment, and I don't think we have a choice but to get serious.

"Games can project the world in either a dystopian or utopian frame, and they allow people to escape and think about the future, both from a hope-frame or a consequences frame. But I think the more that we can get the industry to think about what it can do both as a sector to make a difference, and as a medium to change the world, the better the world will be. So I say it's a choice."