Xbox Series X rewrites the rules of console design - and the power level should be extraordinary

What the massive casing tells us about system performance.

The rules are changing, the nature of console design is radically evolving, the presumptions we have about the core design limitations in building a new games machine need to be re-evaluated. Microsoft has revealed Xbox Series X and its monolithic casing has almost twice the volume of an Xbox One X - and what this means for performance is tantalising. A full-on generational leap in power is indeed coming, but delivering this clearly required a profound reassessment of the core foundations on which existing console designs are based.

The games console has typically defined as a small, living room-friendly box that easily fits within a living room media cabinet. Dimensions have varied from generation to generation, but the fundamental nature of the form-factor has not - until now. In putting together Xbox Series X, the balance shifts. In its reveal coverage with GameSpot, Microsoft asks us to 'do the math' - Series X is over eight times more powerful than Xbox One, and 2x the power of the X, but the challenge in achieving that in a product that launches just three years later than the Scorpio project is not insignificant.

Part of the problem is that processor fabrication technology has not increased in step with Microsoft's ambitions. Assuming it's an accurate image, the 7nm chip we saw back at E3 is roughly the same physical size as the 16nm chip seen in the X - likely a touch larger. Transistor density is unlikely to have doubled, meaning that the primary route forward for increased performance is frequency - and lots of it. Increasing clock-speeds gets more performance and therefore more value from the silicon, but the harder you push, the more power you need. And the more power you need, the more heat you produce - necessitating innovation in terms of thermal dissipation.

And that's almost certainly why the Xbox Series X is so large. I'm not expecting a huge amount of difference in the size of the mainboard or the components attached to it when stacked up against Xbox One X. What I am expecting is a very significant increase in power consumption, plus a big upgrade in the cooling solution in order to manage some pretty challenging thermals. Based on the kind of power consumption seen on AMD's latest PC GPUs based on the same technologies, I wouldn't be surprised at all to see Xbox Series X pulling twice the power of the Xbox One X.

All of this is in service of what Microsoft believes to be the most powerful console of the next generation era. Previously known by its codename of Anaconda (under the Project Scarlett umbrella) the aim has always been to double the outgoing X's prowess with 12 teraflops of compute performance as an internal target. Microsoft sees performance leadership as the crucially important for the core gamer, with Xbox One X - and indeed PS4 Pro - as a successful trial in establishing that committed gamers will pay more for a premium experience.

There is another string to Microsoft's bow - the less-capable 4TF Scarlett console known as Lockhart - which the firm isn't talking about hasn't been cancelled to the best of our knowledge. Lockhart looks weak on paper and there are some inevitable limitations that come with that, but it was developed because power and performance at the highest level come with a certain price-tag attached, necessitating a mainstream-friendly companion product. Series S, any one? I suspect that whether it eventually comes to market boils down to the pricing and performance of PlayStation 5. Even a stripped back next-gen console will have a significant baseline cost.

In the here and now though, it's all about Series X where there is still some ambiguity about just capable the system is. If we 'do the math', in raw teraflops alone, the new console is indeed a 12TF machine based on Microsoft's stated comparisons with Xbox One and the X. However, if we're dealing with performance in like-for-like workloads, the Navi architecture's improvements deliver more perf for your teraflop than prior GCN tech, and our tests suggest that a 9-10TF Navi GPU can provide the requisite doubling of performance up against Xbox One X even before other new architectural features come into play.

I asked Microsoft for clarification on its current-gen multiplier comparisons with Series X, but the firm declined to commit in the here and now to a precise figure. However, our information is that the GPU is indeed 12TF and what are almost certainly well-sourced leaks from Windows Central back this up. The implications are quite remarkable because based on the processor image released at E3 combined with the sheer size of the case, even at a highly clocked 2.0GHz, we'd still require 48 compute units to get the job done - a 20 per cent increase over the Radeon 5700 XT, today's most capable Navi GPU. And that 48 CU allocation wouldn't include redundancy, where we'd expect a further four deactivated CUs to increase yield from the production line. Microsoft surprised us before in how it delivered a six teraflop GPU with Xbox One X, and I'm fascinated by the prospect of similar innovations for Series X.

I'm genuinely looking forward to seeing the final configuration Microsoft has settled upon here. Two of the key aspects in system set-up are being pushed beyond what we currently know as reasonable limits for console design - 12TF suggests a processor at the upper end of the kind of size we've seen in an AMD-based console, possibly larger - and this would be a significant achievement from the new 7nm fabrication process.

It would also suggest frequencies that are appreciably higher than those seen in AMD's Navi-based GPUs - which reverses the situation with the current-gen machines, which are typically underclocked compared to equivalent PC parts. Increasing both area and frequency inevitably pushes up power consumption way beyond anything we've seen in a home console. Our measurements for the first-gen PlayStation 3 currently top the power consumption charts at 209W during gameplay. Based on what we know of Navi GPUs from the existing, seemingly less capable Radeon RX 5700-series, not to mention the size of the Series X casing, I wouldn't be surprised to see the new console move beyond 300W. With that in mind, assurances from Microsoft that the machine has a similar acoustic profile to Xbox One X is very, very welcome.

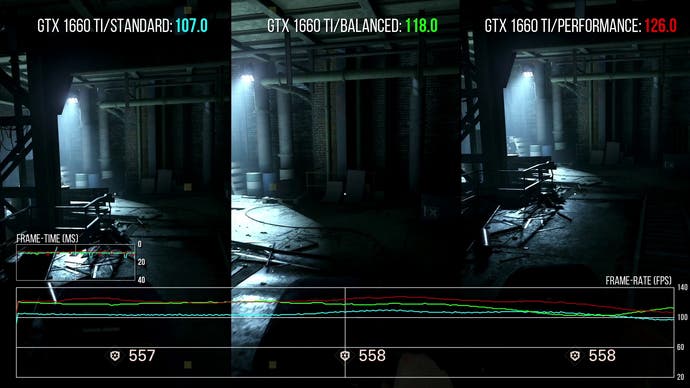

There are further hints about Series X performance and perhaps an attempt by Microsoft to demonstrate a point of differentiation between its hardware and upcoming rivals. The firm describes 'patented VRS' technology - VRS meaning variable rate shading. The idea behind this technology is remarkably straightforward: why should every area of the screen receive the same level of precision in its rendering when human perception itself is far from perfect? Areas of low contrast, or scenes heavy with motion blur can be rendered less accurately and you'd be hard-pressed to tell the difference.

VRS is already implemented at the hardware level in Nvidia Turing GPUs and supported in Wolfenstein: The New Colossus and Wolfenstein: Youngblood, where depending on how you tune it, performance increases by around 10 to 15 per cent. It's only one use-case scenario and obviously the effectiveness of the bump to frame-rate adjusts dynamically according to the content. With that said, it's a good match for the direction real-time rendering is moving in, where technology and art direction is moving towards a more filmic look - a good match for VRS. So again, the teraflops metric doesn't really tally with real-life performance - we should have the boost delivered from superior architecture and any gains from VRS on top of that. With the console vendors having access to future AMD technologies from the road map, this may well be the tip of the iceberg - hardware-accelerate ray tracing is confirmed, but there may be further surprises yet.

The extent to which VRS may be an advantage over PlayStation is also up in the air for now despite Microsoft's claims of a patented technology. The Xbox rendition of VRS is highly likely to be based on the upcoming DX12 implementation designed for compatible hardware in the PC space. However, the extent to which any patent may lock out a console competitor is unknown. VRS clearly isn't exclusive to Microsoft as Nvidia already has supported hardware that runs on two shipped games using the Vulkan graphics API. In turn, this demonstrates that VRS is clearly not exclusive to the DX12 domain. We'll just have to wait for more from Microsoft to see how this shakes out - and the same goes for technologies the firm talks about such as Dynamic Input Latency, which was name-dropped without little explanation beyond what the name suggests (the description sounds reminiscent of AMD's anti-lag, however).

Further details were also shared in the reveal - most of which we know about already. GDDR6 memory is confirmed officially, which was essentially an open secret: the E3 2019 Scarlett reveal trailer showed G6 modules in place next to the main processor. The amount of memory wasn't confirmed in the latest reveal though and the E3 asset seemed to go out of its way to introduce ambiguity in this area. Windows Central's 16GB figure in its report seems highly likely, but the E3 video tossed in G6 modules of different capacities to muddy the waters somewhat.

A maximum of 8K resolution output and a 120Hz limit were also reconfirmed in the latest reveal. It's likely that certain games will be targeting 120fps for Series X, bringing consoles into contention for high-end multiplayer gaming and making them an acceptable choice for PC esports fans. There may well be certain games aiming to natively support 8K displays, but expect to see developers choosing a range of resolutions or continuing to embrace dynamic resolution scaling technologies. As we've stated before, technologies including temporal super-sampling make the concept of rendering at native display resolutions far less of priority than it was for the current-gen machines way back in 2013. We should also remember that the next generation of GPUs will deliver more horsepower for 'smart upscaling', producing even better results. Machine learning features may also play a crucial role too.

The final spec point Microsoft confirmed is a crucial one, and this is indeed new information. We knew that solid-state storage technology would be in place for the new Xbox but what we didn't know was how it would be implemented. Would we be looking at a bespoke solution for ultimate performance? That would imply SSD modules integrated directly onto the mainboard. The reality is that the NVMe standard used on PC now gets the job done on Series X, with Phil Spencer citing a 40x improvement in I/O speed.

Assuming the comparison point is available I/O bandwidth from Xbox One's hard drive, we're looking at 40MB/s for a bandwidth increase to circa 1.6GB/s on Series X - a figure that rises to 2.4GB/s if Xbox One X's I/O bandwidth of 60MB/s is the base number. Combine that with the total removal of seek times (there is no physical head moving around a hard drive any more) and we should indeed be close to the elimination of loading times. In this respect at least, the console will be returning to something closer to its original roots - our hope is that something closer to the original concept of the 'plug and play' console gaming is back.

Confirming NVMe has secondary benefits too in that the route is open for user-upgradable storage that won't compromise on performance. While SSDs are still expensive, costs are starting to drop dramatically. There's certainly space available in Series X for adding extra NVMe drives - the question is whether we'll be seeing 'official' drive upgrade 'cartridges' from Microsoft with certified SSDs within, or whether standard NVMe drives will work. The latter approach offers flexibility and potentially lower costs to the user, but it also introduces the possibility that sub-standard drives may not match the stock SSD spec - which may cause issues. Regardless, the news looks good: stock Series X drives should have superb performance and the door to expandable storage is open, one way or another.

We're still almost a year away from launch, so there are still many questions to answer. Pricing is one of them. The size of the Series X processor represents a significant cost just on its own - and that's before we factor in other pricey parts such as solid-state storage, GDDR6 memory and what is likely to be an innovative (and likely costly) cooling solution. In fact, simply increasing the size of the box alone increases manufacturing and worldwide shipping costs. The conventional wisdom is that a console balances price against performance with inevitable compromises, but there's strong evidence here that Series X subverts this, with more of a push towards getting as much state-of-the-art tech into a console box as possible. Phil Spencer is on record with Eurogamer as saying that he's not going to 'sacrifice performance for the sake of price'.

Certainly, for Series X in particular, that will be true. While it likely didn't translate into a game-changing shift in volume sales, the firm has benefited immeasurably from specs leadership via Xbox One X - and the fact that key titles like Red Dead Redemption 2 offer the best experience on Microsoft hardware has huge value. It's an almost continual source of great PR, but again, specs leadership comes at a cost, the X was $100 more than PlayStation 4 Pro at lanch. Spencer has ruled out an Xbox One situation - charging more than the competition for a less capable machine - but I'd find it difficult to believe that Series X will cost less than $499 bearing in mind its build costs. And equally, I can't see it costing more bearing in mind the PlayStation 3 launch disaster at $599.

The reality is that we will have at least two next-gen consoles arriving during holiday 2020 and prices may adjust, bundles will be pitched, value may be tweaked. Both platform holders will go into battle knowing that $399 is the sweet spot for users, but having made the decision that a true generational leap in console performance is going to be difficult to achieve without charging more. The question is, who's going to pay for it: the users or the platform holders via per-unit subsidies?

In the meantime, there is one clear, key message that I think is of crucial importance and should be music to the ears of the Digital Foundry audience. PS4 and Xbox One launched in an era where the future of the console itself was in doubt and where the vast investments from the platform holders seen in the PS360 generation could not be repeated. After a punishing, prolonged generation, both console vendors delivered relatively conservative designs with clear and obvious compromises in place. All of the signs seen so far with Series X point to a return to the kind of swagger we saw with the reveals of PS3 and Xbox 360 with a genuine desire to push the state of the art.

With that in mind, Series X - and almost certainly PS5 - are built on a foundation of optimism and confidence this time around. There is no compromise in CPU performance in the next-gen design: we're getting a customised rendition of a high-spec PC part. Meanwhile, the PS5 GPU may be shrouded in mystery, but if the indications are true for Series X, Microsoft has developed a console GPU that is more performant and more feature-rich than any Navi part AMD has shipped in 2019. Your next console will be a lot bigger than your current one and it may cost more than you expected, but putting this level of power in a mainstream piece of gaming hardware is hugely exciting. Technological miracles were achieved from the current-gen machines despite their limitations - and the possibilities represented by their successors are mouthwatering.