Hotel Dusk: Room 215

Please go easy on the minibar.

The first thing people say when they see pointy clicky adventure Hotel Dusk is, 'That looks like the video by AHA from the 80s!' So it's the first thing I've said too, so it can be mentioned, and now forgotten. Far more interesting is examining how Hotel Dusk's animated pencil sketches look without coincidental comparison, but it does at least provide a vivid reference point for those who haven't seen it running.

Kyle Hyde (and yes, he's very proud of his name) is a door-to-door salesman by trade, but with a slightly peculiar edge to his business. His jobs require not only hawking dodgy late 70s technology (as this is when the game is set), but also finding 'lost' items for clients. However, three years earlier he was a cop for the NYPD, until he was forced to, for reasons not explained until very near the end, shoot someone close to him. His life is quite clearly not what it once was, and his deeply cynical attitude provides the lens through which you view the game.

Sent to Hotel Dusk, Kyle finds himself booked into the Wish Room - a room, it is claimed, that will grant your wishes when you sleep there. And with this put to you at the very start, it triggers ideas that were so beautifully explored in last year's Sci-Fi channel mini-series, The Lost Room. Magical rooms, mysterious objects, peculiar characters... However, despite this impression, Hotel Dusk isn't going anywhere near any of that. This is a story set very much in the real world, but with, well, rather a lot of coincidences.

It's from the same team that created Another Code, which was rather inexplicably heralded as the great white (or black or pink, and in Japan, a sickly blue) hope for adventures on the DS. It was, I think hindsight can confess, a weak game with a few lovely ideas. Three, in fact. Three superb puzzles that saw the instrument with which you played the game - a folding plastic console - playing a significant role as you interacted with the game's world. Reflecting one screen in the other, closing the console to print the top screen on the bottom - these were splendid ideas, lost in a trite and incredibly short story. It was, however, exciting potential. The DS you held existed within the game it was displaying.

Hotel Dusk definitely addresses the brevity issue. It's huge in comparison. However, this is mostly due to the extraordinary amount of conversation throughout. This is Phoenix Wright levels of chatter, except with one rather important element absent: the funny. Dusk is about noir, its inspirations the murky detective fiction that now only exists as spoof or homage. Cing have opted for the latter, and as such everything is taken very seriously. For a really long time.

The hotel has a number of guests, and a few staff, all of whom have stories to tell, and secrets to hide. Hyde really only wants to get his job done and go home, so it's with a depth of reluctance that you start sniffing into people's pasts and presents. In fact, it's always motivated by Hyde's driving goal, to find his former partner, Bradley, missing for the past three years. It seems, by peculiar circumstances, that so many people in the hotel are linked to each other, and in turn, linked to Bradley. So you chat, and you chat, and you chat. And then you chat. Chat for a bit, then some chatting, solve a child's jigsaw puzzle, and then have a bit of a chat.

Importantly, these chats, while overly long and madly frustrating in their inability to be sped up, provide a depth of character so devastatingly missing from most games. People have motivation, and while they're reluctant to reveal it, learning why the drunken father is so distant from his daughter, or how the author came to find fame and ultimately destroying guilt, is the reason to play the game. It's not, however, for the puzzles.

Cing have somehow, once again, repeated their biggest mistake with Another Code: they've forgotten to put enough puzzles in. In fact, this time around with a game lasting about four times as long, they've put in relatively fewer. When the first two are both solving pre-school jigsaws, it doesn't bode well. There's a couple that lift a similar (and still nice) idea from Code, but sadly it's the same one twice. And then after that it's all too simplistic, hindered only by your not having the correct inventory item with you, because when you found it earlier the game wouldn't let you pick it up. A chapter later and you can, but how are you supposed to know that? And a similarly criminal mistake is made twice, where you're told you can hear a noise at the end of a hallway, and are then expected to go through three rooms' worth of furniture searching (that you've already done before when you first went there), trying to find the one object that will have changed or been added.

However, as annoying as this all is, it doesn't condemn the game to doom. Finding new objects does tend to lead inevitably toward that with which it must be combined, which gives you the continued feeling of progress and success that an adventure must provide. And as the mysteries deepen, and the threads begin to intertwine, you start wanting those endless chats, because they'll reveal the next snippet, the next bit of information that will lead you closer to solving the myriad mysteries that have been set up. It becomes, to use a horribly over-used phrase, an interactive novel.

Perhaps the factor that won my cynicism and frustration over the most is the development in Hyde's character. One resident in particular starts to chip away at his carefully constructed outer shell: Melissa. She's nine years old, and staying with her miserable and unpleasant father, told that she's going to get to meet her mom very soon, but only if she's good. Her mother, you learn, has been missing for a few months, and it's impossible not to sympathise with the equally brattish and cute Melissa. Especially when you learn she didn't even get a Christmas that year, and begin the little side plot of arranging a mini-Christmas party for the kid with the help of some of the hotel's staff.

Then there's Helen Parker, an elderly woman who is waiting to meet someone; Martin Summer, a dreadful bore and author; DeNonno, a former petty thief and foil of Hyde during his policing days in New York, now, coincidentally, working at the hotel; Iris, grumpy and pretty young woman; Mila, strangely mute girl who is clearly sitting on many secrets; and, ooh, at least seven others. As I said, a lot going on, and a lot of interconnections and histories to explore, and as Hyde's character develops, perhaps even help.

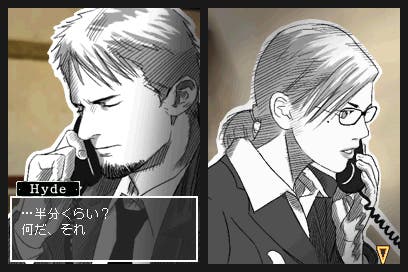

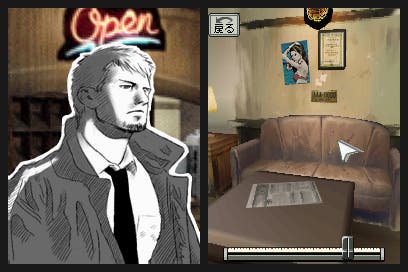

So to the looks. The DS is held sideways, somewhat like a book. This, like so much else in the game, is no coincidence. Interactive novel, remember. For the movement, the left screen is a first-person view, the right a top-down plan of the room, navigated by holding the stylus where you wish to head. The characters are the previously mentioned pencil sketches, surrounded by a white border as if they've been cut out from paper and then stuck onto the backgrounds. And such beautiful backgrounds, watercolour paintings that aren't quite finished, the brushstrokes not reaching the edges, as if a work in progress. As characters talk, the two screens are occupied by the members of the conversation, their black and white bodies occasionally washed with faint colour. Upset someone and a brushstroke of red will spill down their body. Get to know someone and their face might flush with hues. It's an absolutely stunning design idea, and despite the blurring of close-up objects, is constantly emotive.

Cing are clever people. They were clever with Another Code's meta design, and they're even more cunning with Hotel Dusk's presentation. Rather than spelling out their metaphor and meaning, the effect is left to make its impression on you, and be interpreted as you see fit. Why are these people so roughly sketched, and so frequently lacking colour? Why isn't the front door finished, and why are the walls of the lobby fading to white paper?

If only there weren't so many mistakes. If only you weren't punished for asking the wrong question in a conversation (and really punished, forced to go back to your last save [SAVE OFTEN] and have the same unskippable conversations all over again for painful minutes). If only inventory items were available when you found them. And if only the puzzles were aimed at people over the age of nine. Because so much is right about this, and so much is worth exploring. It's a game that really understands people, and their complex motivations. And yet so often forgets the motivations of the people playing an adventure game. It's a game that knows how to use the DS to great effect, and how the stylus can be so casually and effectively. But its ‘minigames' are perfunctory and underdeveloped.

But it deserves attention. It deserves it because I've realised I could write a thousand words on each character, exploring their behaviour and relation to the ever-evolving central thread. It deserves it because I've had to really hold myself back from becoming deeply pretentious and waffling on about Brechtian estrangement again, remembering that my interpretation of the presentation might not be yours. (Your wrong interpretation). It's made me think a lot, and I suddenly found myself waffling on at great length about how interesting the characters' behaviours are to an innocent passing housemate. It makes lots of mistakes, but it has substance, as well as the very finest style.