Darwinia Review

Games evolving into its own little niche.

Time for a Monday neologism: Post-genre.

The theory goes like this. If we're looking at computer games, when videogame manufacture was first democratised by the appearance of home computers no one had any idea what they were doing so they were forced to invent by necessity. Ideas were thrown together just to see what operated well, or even operated at all. These times I'll describe vaguely as "pre-genre".

Eventually, however, they hardened into solidified idea-clusters which were the modern genres, each with specific characteristics. In fact, if a game failed to fulfil some of these criteria, it could often be dismissed as a bad game, when in reality it was just a bad example of a particular genre and really succeeded as something else. Games reached the "genre" state at different rates. A late appearing genre - like the first-person shooter - was still pre-genre up to the point where Doom appeared. Take the original System Shock, developed by Looking Glass. Since there had never been anything quite like it before, they created something that still stands slightly apart from the FPS. If it appeared a year later, its controls would have probably been more akin to Doom because the genre had properly defined itself.

Genres are a great aid for the gaming public as they get used to thinking about and playing games. We reached the point where there are people who don't just like the idea of "games" - they like specific genres or sub-genres. Or even singular mods of games: I'd imagine there are people out there who haven't played another game seriously since Counter-Strike appeared all those years ago [in which case, get help! -Ed].

Except we've started to move past that. Genres saturate and eventually the palette becomes sated. As we want a fresh thrill, the genres start to blur again, in ways more sophisticated than the action/strategy games like the (brilliant) Hostile Waters and Battlezone. Influences from other genres build up to the point where the game no longer really belongs to that genre.

At this point, we've entered the realm of the post-genre. It's what the progressive, intelligent gamers are playing. Simultaneously, it's also a terribly populist movement. After all, what genre does Grand Theft Auto belong to? None. It's about a half a dozen, blended seamlessly into a fluid, expressive form. Genres have burnt out, and we hit the post-modern point where everything is up for grabs again, the entire history of gaming turned into beautiful decadent cocktails.

Which leads us, eventually, to Darwinia, the first great post-genre game of the year.

It's a terribly difficult game to explain. A game scientist could be able to distil at least a couple of dozen influences from it, from the large scale ones (like the touch of real-time strategy in the way you control and create your units) to the small ones (the way the centipede's attack patterns are a direct reference to the old-skool videogame of the same title). But noting all these separate bits would just confuse everyone... however a more streamlined approach just misses huge chunks of what make the game interesting.

It's important to just stress that all the parts come together in an entirely understandable form in the actual game. Its sense is best experienced rather than described.

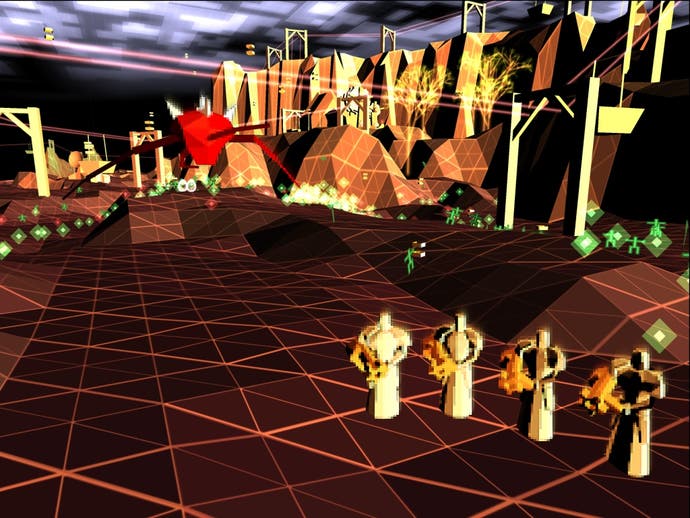

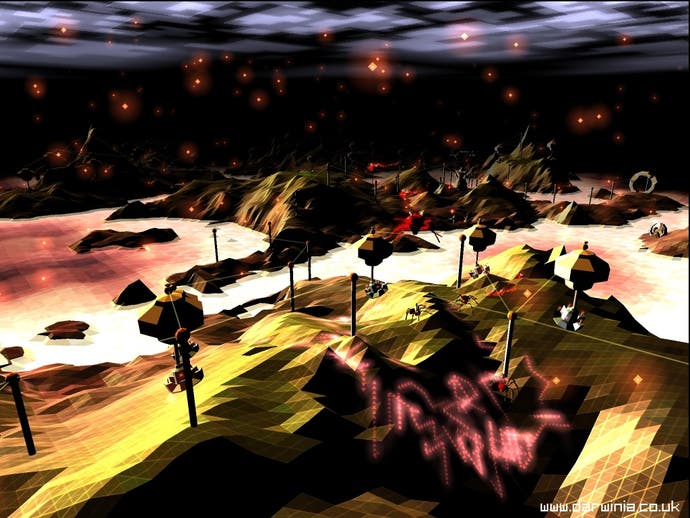

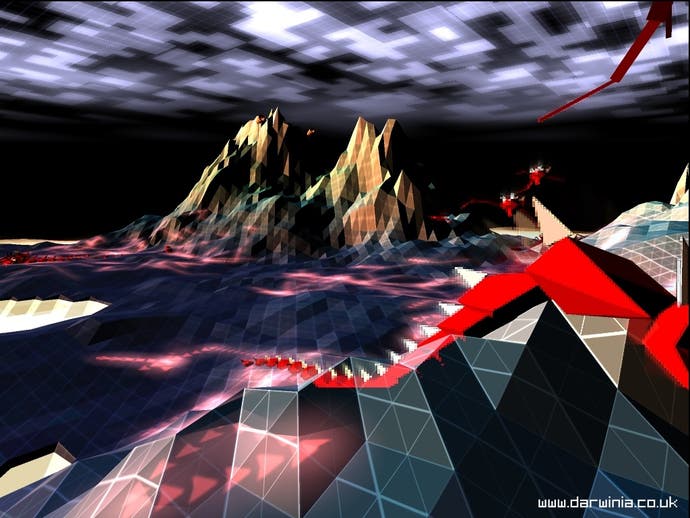

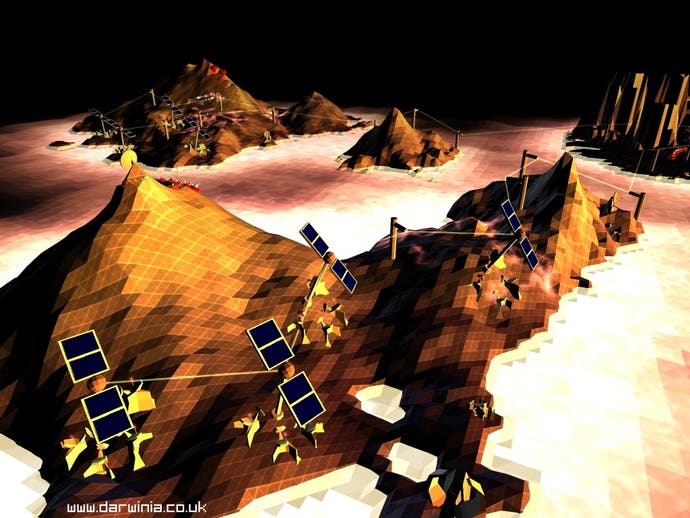

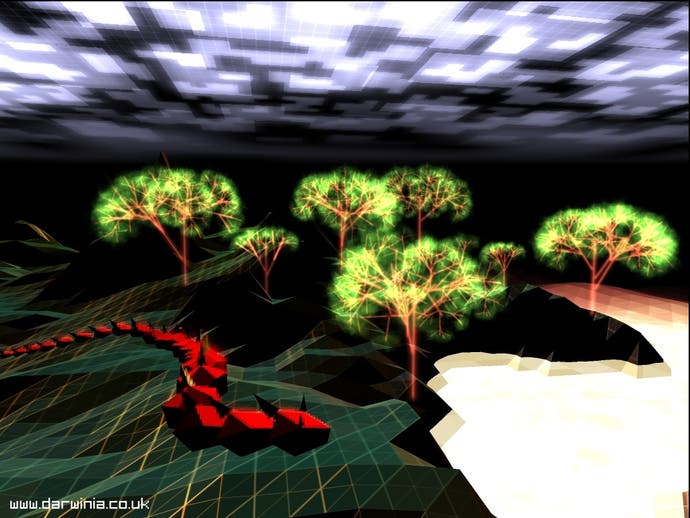

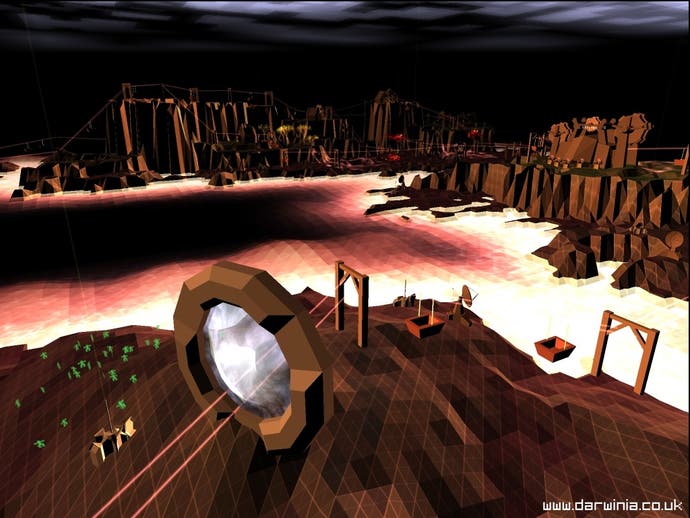

Set in a TRON-styled retro fantasia world, you're charged with clearing out a viral infection. To do this you control a squad of programs in a similar manner to the classics Cannon Fodder and Syndicate. Left click to move around, right click to fire and both at once to fire a heavy weapon. Your opponents cover the terrain, and vary from the weak mass of swarming virii to the absolutely fearsome soul-destroyers who float above the battlefield, sweeping down to annihilate everything they touch. You move around. Enemies are shot. That's the basics.

Things are enlivened by the more strategic elements. When anyone dies, they drop a "soul". These can be recovered by one of your engineer units, brought back to a structure and processed into a Darwinian: the natural, friendly inhabitants of the world. Initially defenceless, these can be manoeuvred around the landscape by converting one of them into an officer. Missions often involve moving these to a position without being destroyed, a little like Pre-GTA DMA classic Lemmings.

(Notice how often the word "classic" is appearing in this review. Darwinia only takes from the best.)

The real-time strategy elements appear more because, to start with, you're only able to have three separate programs running at any time. Units are summoned in a draw-shapes-with-mouse method akin to Black & White's, and can be dismissed with a simple CTRL-C (Another amusing touch is that the game takes Windows short-cut conventions and places them into the game - for example, with you skipping between your units with a ALT-TAB). Dismissing doesn't matter, as you can always create more, as long as they're close to a base you've captured.

This means that the game doesn't have a classic "failure" state. Rather than tedious quick-loading, you're always free to go back and have another crack at the situation - in fact, the disposability of your charges ends up becoming a prime tactic. Suicide-approaches are entirely acceptable. Dismissing a unit the second their task is performed to free a program slot so you can re-create them on the other side of the map is a useful time-saving approach. While it's possible through error to make a level uncompletable, it's up to you to realise this and press the reset button.

Despite this, it's also a uniquely challenging game. In fact, for a game where you can't actually "fail" it's blisteringly tricky at times.

This is the core of why Darwinia is so brilliant.

Most modern games are made to be beaten, to offer a series of amusing and distracting phenomena to reaffirm your self worth and then disappear into the night. They're submissive little things, doing anything to make you, its master, happy.

Not Darwinia.

Darwinia looks you in the eye and dares you to take it, which to continue the slightly tacky metaphor, makes it a much better lay. It doesn't make it easy for you. It doesn't provide answers - only the tools. You learn the limitations of what you have available - and that of your opponents - and exploit them. Things that appear impossibly difficult can become mere trivialities when you have a moment of revelation and understand the game's hidden mysteries. When I'm not playing it, I've found myself having an idea about how to go about something, then having to run back to the PC, load it up and try it out.

The assorted viruses are a brilliantly constructed foil, with the different species interacting in carefully crafted ways. Centipedes can be shot into separate smaller parts, then regenerate into larger ones. Spiders collect souls, laying eggs which hatch into new swarms of Virii. Generators launch pods to islands that have become depopulated of virus, which pulse for a while before hatching into a new infection to help replenish the ranks. While it's clear that you're not fighting a human intelligence, you're fighting an animal intelligence that acts as part of almost an integrated ecosystem. The challenge is to work out how best to disintegrate it.

And you can't rest on your digital laurels. Since each level changes the stakes so much, you're always forced to learn something new. Ideas never over-stay their welcome - the Ants are one of the single best examples of interesting AI I've ever seen in a game, but fighting them is only a necessary part of one level. It's a game which starts as something you find interesting but presume will eventually run out of steam, but instead it constantly escalates. There's a point after the half-way stage when you realise that the developer isn't going to run out of twists to throw at you, at which point you submit and admit it's genius.

It's not perfect. With only 10 levels, you may consider it a little short. There are some problems with the controls involving teleporting the Darwinians along the radar-discs. Some levels - the one with souls falling from the sky - created slow-down enough to force me to switch to the charmingly named "I need an upgrade" option. There's a level where, on first try, you'll probably make it impossible to complete without realising until its too late, which is frustrating. A few other, minor bits.

Not Perfect. What is? God. And if you'd rather have some old guy in robes with a beard than a post-genre neo-classic, you're not my friend anymore. [Why does his robe have a beard? -Ed]

There are a few other problems which I don't really consider problems. Speaking generally, it strikes me already that its reviews are going to be brutally mixed, though the writing will tell as much - if not more - about the limitations of the reviewer as the limitations of Darwinia.

Two complaints which I expect will turn up fairly regularly are those about its path-finding and the difficulty with the gesture system. A click at a distant location will lead to a squad marching in a virtually direct line with scenery obstructing their passage, rather than a unit finding the correct route to get there by themselves . Sending such an order can lead to you finding your charges stuck on an impassable slope or even destroyed by an errant lump of scenery. The latter is a simple extrapolation that, in a heated situation, despite the generosity of the gesture system, can lead to mis-ordering, which causes failure of your carefully constructed tactics.

Fine, perceptive complaints. If you were reviewing an RTS.

Imagine for a second that I made the first complaint about - say - Prince of Persia; that by holding down one button the Prince wouldn't make his way past all obstacles. You'd think me mad, noting that would remove the point of the game. The manipulation of your avatar to avoid obstacles is part of its design. The same's true of Darwinia - it's not a game where you sit distantly from your squads, but one where you have to be hands-on. Yes, it's a design forced upon Introversion by necessity (that is, the time to do better path-finding would be so extreme to hurt the rest of the project - I haven't mentioned this is a bedroom-coded game yet, because it's really irrelevant. Good games are good games) but it's still design (That is, we can't do path-finding, so let's make a game where it's about being more hands on with your men like Cannon Fodder).

Similarly then - though thankfully for the cynics in the audience less tenuously - the latter complaint. Imagine someone whining about a combination of keys or a roll of the stick in a beat-'em-up being required to set off a special move? No, thicko. The fact it requires skill is the point. The fact that pressure can break you is the point. It's a true case of not the game failing - but you failing. The game also eases you into the gesture controls, never overloading you with shapes to remember.

Hmmm. The pre-emptive arguments are always a sign that a reviewer's getting too involved, but... well, I am involved. For something so abstracted, it's a strangely emotive game. A journalist friend of mine describes how, when the in-game justification for the souls-system was explained, he was biting back tears at its poetry. He laughs and tells me that it's a game that doesn't need good review scores - it needs evangelism. By the final level when you see hundreds of Darwinians swaying in time to their very own Tower of Babel, you begin to see his point.

Forget games with real-time physics. This is one has real-time metaphysics.

It's this year's underground classic, this year's Rez, this year's Ico, this year's... well, this year's Darwinia. It's a game that justifies your sense of your brilliance and gaming's sense of brilliance.

Play Darwinia. Be Brilliant.