The Tao of Beat-'em-ups

Part 1: The evolution of a genre, 1976 to 1985.

"A goal is not always meant to be reached; it often serves simply as something to aim at." - Bruce Lee

Fighting games and beat-'em-ups have been a staple diet of many gamers for 25 years. But they've also carved out a dichotomous genre that sits alone on one side of a gulf separating it from the rest of the gaming community.

Often regarded as overly austere, and perhaps even too lowbrow for the serious gamer, beat-'em-ups suffer the stigma of being the idiot cousin of the gaming industry - an unwelcome and vulgar relative who turns up at family parties drunk, does briefly entertaining elephant impressions then starts a fight with the neighbours. Inherently shallow and restricted by the very genus it was born into, the beat-'em-up seems to contradict what many users consider being a worthwhile application of a computer or console.

Despite unashamedly enforcing the stereotype that videogames are a socially irresponsible pastime that encourages aggressive behaviour in the players, the genesis of beat-'em-ups signified a profound evolution of the industry that belied the superficial nature of the games themselves.

The genre sprang up in a number of different, and apparently disconnected, sources all at once, but the purpose for its arrival is more significant than its founding titles. While most early games delved into more outlandish fantasy concepts like piloting spacecraft or adventuring through some dark Tolkienian world, the fighting game was the first attempt to explore, and digitally recreate, the human form. A new realm of macho caprice was realised that placed gamers on the screen in a very real sense, and allowed them to sample the fringes of heroic possibility - fighting without fear, pride or pain; becoming Bruce, Jackie, Bronson and Eastwood for a few intense moments.

Coupled with the sheer, unabashed entertainment value that beat-'em-ups offer in quantities no other gaming genre can come close to achieving so immediately, fighting games quickly came to represent a vital industry anchor point which connected developers with the gaming audience.

"All fixed set patterns are incapable of adaptability or pliability. The truth is outside of all fixed patterns." - Bruce Lee

The first games to attempt the task of portraying human combat didn't actually set the standard for the prolific genre that was to follow. If anything, SEGA's 1976 arcade machine, Heavyweight Champ, and Vectorbeam's 1979 coin-op, Warrior, came closer to proving the incapability of a game system to represent hand-to-hand fighting (or sword-to-sword as it was in Warrior's case) than it did toward establishing a new sphere of arcade potential.

SEGA, at the time, seemed to concentrate more on developing imaginative control systems rather than gameplay (something which has certainly worked for Nintendo recently, it must be said). The black and white boxing game employed two "boxing glove" controllers (one each for the two players) which moved up and down for high and low punches, with an inward movement for striking. While the controllers were a decent enough gimmick, the actual on-screen match wasn't much more than an unresponsive cross between a Punch & Judy performance and a pixellated episode of the Black & White Minstrel Show.

And, although Warrior was something of a technical accomplishment in its own right, it wasn't a title that could be classed as the progenitor for the forthcoming fighting game revolution either.

Vectorbeam adopted a bird's-eye view of two armoured knights, duelling it out in a treacherous, pit-riddled dungeon. In many ways this was a wise premise for a new style of game to adopt, even if it didn't inspire the impending genre directly. At the time, the race was on to visually realise the wealth of fantasy adventure games that dominated an entire corner of the games market, and the medieval setting, complete with dark, dank and dangerous dungeon, was perfectly in keeping with this graphical race.

The vector drawn knights were equally exciting; expanding on the limited, yet renowned accomplishments of Atari's line drawn games. Unfortunately, the rest of the technology let Warrior down, and unstable electronics coupled with the need for two simultaneous players meant a short and uncelebrated life for the coin-op. Naturally, the volatile nature of the machine's innards and relatively small production run makes Warrior a prized possession of modern games collectors.

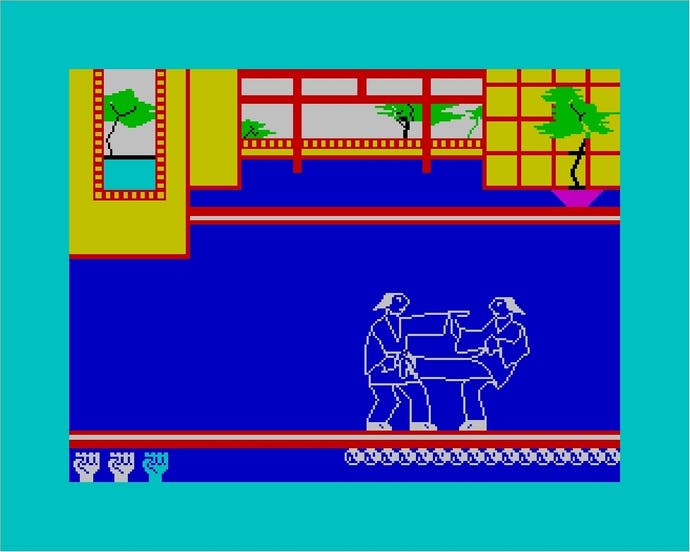

A depressing five-year gap followed in Warrior's uneventful wake. All at once, a host of new games appeared across different systems that shared little in the way of obvious inspiration. Quite what signifies the relevance of 1984 to the fighting game it's difficult to comprehend - suffice to say this was the year that technology crept past some minor, intangible milestone that unlocked the potential for digitised combat.