Bahnsen Knights review - bringing the Pixel Pulps home in style

RDWRER.

One of the special things about games, and a thing that I have always struggled to articulate, is that the good ones, the really good ones, take you deep. Have you ever noticed how small a TV screen or a computer monitor actually is? Let alone the dinky grotto skylights of a Game Boy or a Vita. These screens take up such a small portion of your overall vision, unless you're crowded in really close. But when the right game comes along, the rest of the world just irises out. You don't see the border of the screen. You don't even really get a meaningful sense of its flatness anymore. A good game draws you deep inside.

This is what William Gibson called cyberspace, I gather. He tried to picture the world on the other side of the scrolling PC monitor and a whole landscape was born. But it doesn't feel like cyberspace here very often. I always feel that I emerge from games after playing - that I have to kick my way up to the surface from deep underwater. Some games don't replace the world around them in a delicate manner so much as absolutely flood it. A great game always leaves me feeling like I've just crawled, soaking, out of the drum of a washing machine.

Bahnsen Knights is one of these games. For the few hours this week in which I played it, it was a comprehensive submerging of the rest of the world. I was in there deep, just as I have been with the other two games in the Pixel Pulp series to which Bahnsen Knights belongs: Mothmen 1966 and Varney Lake. So this is a review of Bahnsen Knights, but it really feels like a belated review of the whole Pixel Pulp project. And that's because, right at the start, I got something wrong, and it's upset me in some dim, muttering way ever since.

The Pixel Pulp games are a glittering oddity. I guess you could call them visual novels, because that's a handy genre that exists, and because these are stories that you page through, occasionally making choices, and because the prose bears the unmistakable ring of proper literature, being deeply interested in people, memory, doubt, and that strain of experience that requires a proper examination before it sits neatly in the brain. As the names suggest these are all horror stories, weird stories. Mothmen 1966 is about everyone's favourite cryptid. Varney Lake is about a lost childhood summer spent with a vampire, and Bahnsen - well, we'll get to Bahnsen.

Now that I've played through all three Pulps I can see other shared preoccupations running through them too, like phone cables stitching together a late-night party line. There are characters who crop up in each game. The colour scheme strobes from the sickly cyans and toxic greens of Mothmen through the thatched yellow of Varney and into the throbbing sunset reds and pinks of Bahnsen in a way that, in retrospect, seems perfectly judged and tightly controlled. Oh yes, and each game offers its own Solitaire variant too, buried deep in the narrative.

Pulps. Visual novels. And yet that's not half of what these games are. Because the Pixel Pulps also tie into another tradition - CGA games from the late 1980s and early 1990s. They're literature, but they're also software that wants to be software, that wants to draw attention to itself as software.

Those CGA games always came on discs, swapped amongst classmates, and they belonged to a time where there was no clear space for the PC in most people's houses. Down by the bottom of the stairs? An awkward nook in the kitchen? As a result people encountered CGA games in all kinds of ill-chosen, illicit, liminal spaces, and the games themselves were perfect for that. A handful of lurid colours, home-made graphics, possibly planned out in an exercise book and then pieced together one pixel at a time, and no established means of controlling the action. Did you want to type? Select verbs from a list? Learn to read and interpret runes? Even before the Pixel Pulps came along this was gloriously cursed territory, crackling with strange potential.

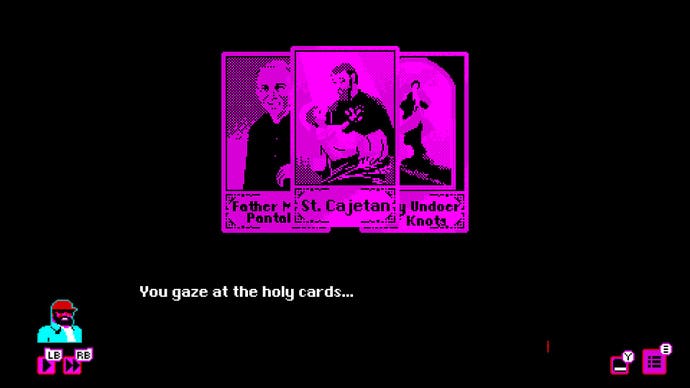

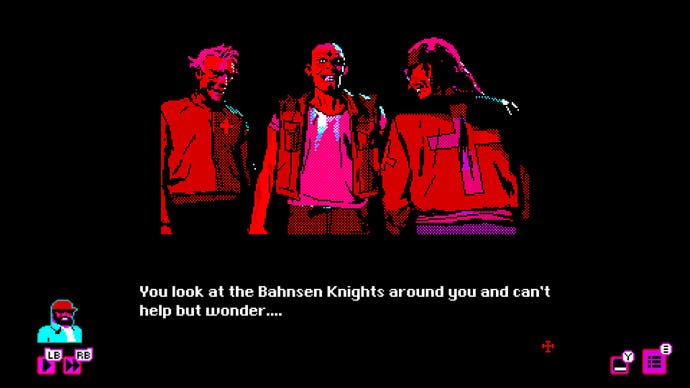

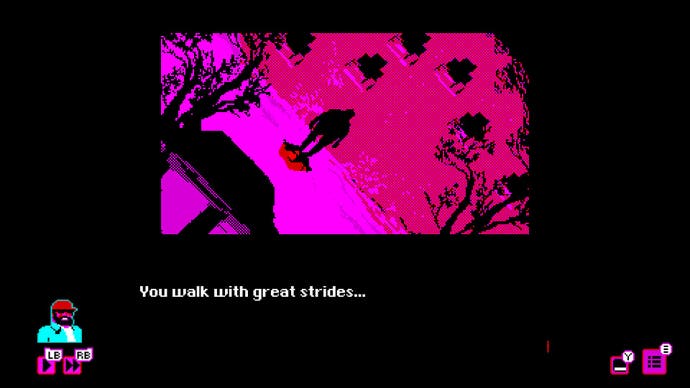

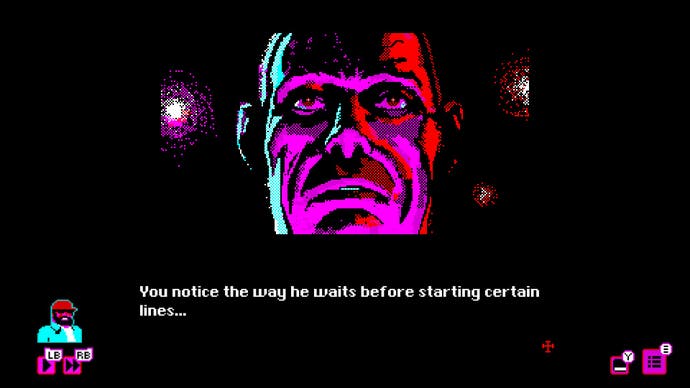

The Pixel Pulps use the aesthetic of CGA games, with narratives unfolding through a series of beautiful hand-crafted images. Long shots, masters, two-ers, and fidgety up-close portraiture when things get nasty, this is exactly what it felt like when early games grappled with montage and the language of cinema. Pixel Pulp games have a lovely abstract sense of landscape - the details stand out sharp while backgrounds dither into cross-hatching. Characters, meanwhile, are straight out of old EC horror comics: the grown-ups feel very grown-up in that way that always used to give me a chill: jaws are firm, creases are fixed and deep, and hair and eyes are often wild, hinting at some internal mania. Players are thick-lined with middle-age.

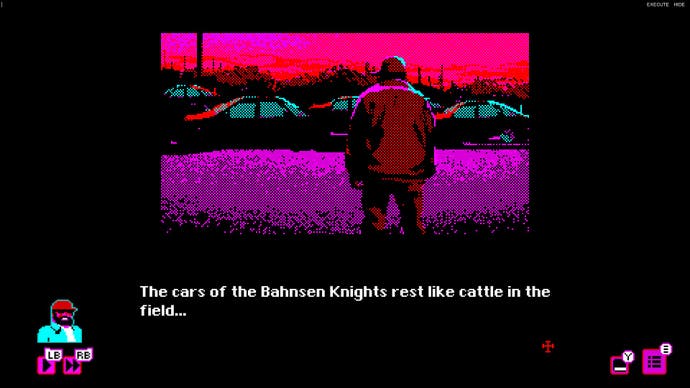

Bahnsen Knights uses all this to spin a new tale: one of a cult, a religion based around roads and cars, run by a trashily charismatic man and finding its moment in a flat midwest landscape tormented by wild weather. The player is cast as a member of the cult who is also working for the government, trying to crack the whole organisation open for personal reasons that are revealed slowly throughout the game. Everything is revealed slowly throughout the game, a game whose internal pulse beats to the appearance of new information. I will spoil no more of it here, not least because, after two playthroughs, I still haven't seen all over it. Choices matter in this world, particularly when you don't know you're making them, and you won't see all of Bahnsen Knights in one, two, or three passes.

Art-wise, I'm tempted to say that this is a high point for the series. The faces of your fellow cult members are sharp and thuggish, like members of a forgotten New York band from the 1970s, the kind that might have harassed live poultry on stage to make up for the fact that they couldn't really do much with their guitars. The player character, meanwhile, is alternately saggy with sorrow and punchy with a desire to get to the truth. The narrative unfolds across bars, barns, and empty highways, a game made for rosy dawn and radioactive sunsets. When it comes to transitions, images seem to freeze, even though most of them didn't move to start with, and then the picture will fragment into little specks, single pixels. It's glorious.

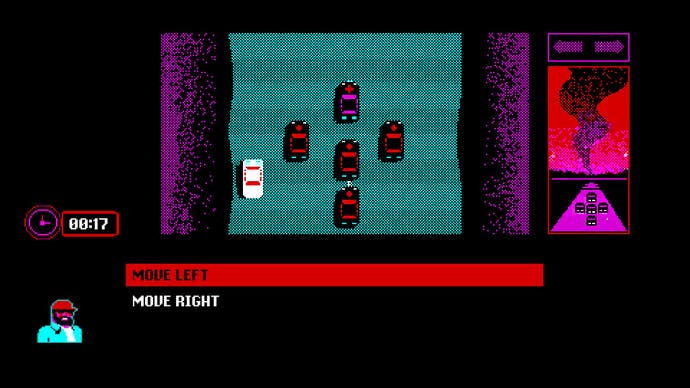

Here's the important thing, though. Bahnsen Knights, like the other Pulps, also uses the mechanics of CGA games, which is to say it's endlessly experimental but with very simple inputs. You page through conversations and make choices by selecting sentences on the screen: this or that, go there, talk to this person, break into this room. But through all that, strange opportunity blossoms.

This is the thing I got wrong. When I first played Mothmen 1966, I thought it was all elbows. I'm playing Solitaire, but I'm doing it with text prompts?And yet, in fact, this is a crucial part of why games like the Pixel Pulps can take you so deep. Their mechanics are not dressing, they are a way of being in these worlds, as they should be. They are a doorway into a weird space in which you should never be entirely comfortable.

This works particularly well for Bahnsen, I think, because you play someone working undercover, someone who's lying to absolutely everyone - even, in the game's most emotional moments, themselves. So while the game offers trust counters underneath main characters so you can see how convincing you are moment-to-moment, and while the game neatly tracks the beers you drink each night as you try to blend in but also try not to get too drunk and blow everything, it's the text prompts that really sell your confusing position. Everything is tentative, speculative, likely to turn into a fumble. Every conversation must be inched through unnaturally. At one point I had to go through the desk drawers in an office I wasn't meant to be in, hoping all the while that I wouldn't be interrupted. It turns out that there is literally no better way of getting to the fidgety all-thumbs-tension of this scenario than using text prompts. Next draw, open, close, next draw... It was magic.

Bahnsen Knights is magic in general, whether it's the plot that is so light-handed at pencilling in its themes, leaving the player to do the crucial part of writing that ties the narrative together, to the way that the action finds interesting gaps for you, whether you're manoeuvring a car on a busy road or realising that you have run out of interesting things to say to a vital contact, or whether you're using a Tarot Card system to organise the case you're making against the enemies who you've had to pretend to be pals with. It takes you deep. I emerged from it all in a daze, and then I went straight back in to see what else was contained within its space.

Listen. I want to end by talking about why this game, this series, moves me in such a specific way. It's something to do with the fact that its worlds are so encompassing but also so self-contained. They draw me in, using great art and design and yet requiring my imagination too, but at the end I return to my side of the screen and I'm wonderfully, agonisingly shut out of everything again. Ultimately, by doing this, I think these games take me back to the first threshold, back to where my love of games began. And now I think about it, this love doesn't begin where I assumed it did.

Prior to CGA, prior to the home Commodore 64 or Vic-20 even, I have a memory that seems to be the true start of it all. Primary school, my first year, I suspect, and I was taken out of class one grey morning by the school nurse and made to sit in this strange space between classrooms - not quite a corridor but not quite a room, a boxy cluttered stub of a space, outside of the mild rituals of a day at school. The lights were dimmed and after a few seconds of fussing I was made to peer into a beige machine through a heavy glass lens.

An eye test. In the expectant shadows, a vision blinked into view. It was a hot air balloon, brightly coloured, hanging above a desert. A view with a sense of perfect, almost heightened stillness. I realise now that I must have been moved, in my confused childhood way, as I looked at the balloon: it has stayed with me ever since.

This was something new to me - fabricated and mechanical but utterly transporting. I felt like I was suddenly somewhere else, inside a private landscape, but an expansive one, and yet separated still. How could that be? I was with the nurse, and surrounded, through the walls, by teachers and school children, but only I could see the balloon. There was a sense, perhaps, of necessary distance, and of being in the right place at the right time. I almost suspected that if I had taken another look a minute later, the balloon would have gone.

A copy of Bahnsen Knights was provided for review by Chorus Worldwide.