Banging the DRM

The history of anti-piracy.

"As the majority of hobbyists must be aware, most of you steal your software. Hardware must be paid for, but software is something to share. Who cares if the people who worked on it get paid? Is this fair?" That's Bill Gates, ranting about software piracy. He wasn't complaining about the proliferation of dodgy copies of Windows 7 flying about in the torrentsphere, however.

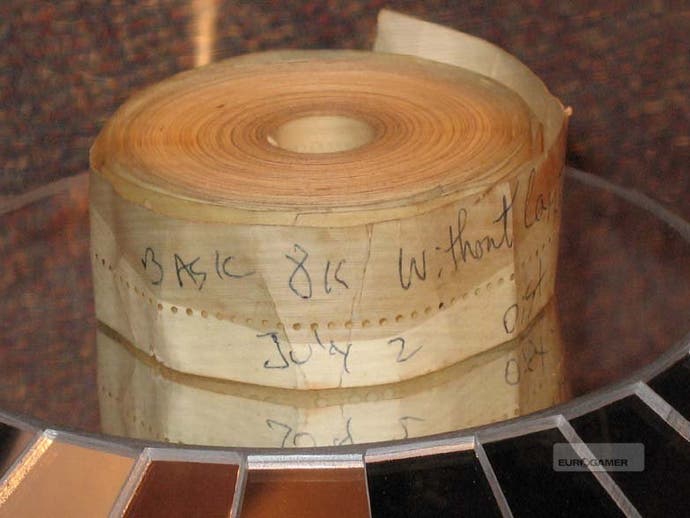

No, this is from an open letter written in 1976, back when Microsoft was still Micro-Soft, directed at anyone using a stolen copy of Altair BASIC. The fact that Altair BASIC came on a reel of analogue paper tape clearly illustrates that the entire history of commercial software can be seen as an ongoing technological war between those selling the code and those determined to take it for free.

Today it's Ubisoft in the firing line, its decision to force players to remain online at all times in order to validate their software attracting criticism and anger, especially when server problems have prevented gamers from even loading legitimately owned software.

Prior to that, it was EA getting gamers' knickers in a twist with its use of SecuROM, which placed strict limits on titles such as Spore, originally requiring online verification every 10 days and only allowing the game to be installed three times. Somewhat inevitably, the draconian restrictions had little impact on the pirate community. Spore was cracked and released online days before it went on sale, and became the most widely copied game of 2008. Once again, the only people inconvenienced by the DRM were the people who had paid for their game.

Things weren't so elaborate back in 1980, but even the earliest floppy discs for computers like the Apple II used software copy protection based on how disc sectors were written. This rudimentary system was immediately attacked by programs such as Locksmith, the first "nibble" copier, which chugged through data half a byte at a time.

For most gamers, certainly in the UK, copy protection first became noticeable in 1984 with the release of the Spectrum classic, Jet Set Willy. Like other early home computers, the ZX Spectrum was an open invitation to pirates thanks to its simplistic storage media - anyone with a double tape deck could insert a blank tape, hit play and record and run off a copy of a game for their mates.

With the sequential nature of the tapes precluding any sector-reading solutions to the problem, publishers had to innovate, coming up with obstacles that made copied versions of the game more hassle than they were worth.

For Jet Set Willy, this came in the form of a coloured grid on the inlay card. To load the game, players had to correctly enter the requested colour from a randomly generated grid reference. With domestic scanners still a fanciful pipedream, and colour photocopiers something of a rarity, unless you had time on your hands and a big stack of felt tip pens this simple coloured sheet created a daunting roadblock for anyone after a hooky copy of Miner Willy's second adventure.