Banging the DRM

The history of anti-piracy.

"The largest sales of any title (back then) occurred within the first week of release", he posted. "Not everyone who had an Amiga had programming skills and we were attempting to deter casual copying at this level. Our hope was to delay the proliferation of copied disks for a short amount of time in order to maximise sales. The measure certainly prevented the casual, non-programmer copier from just duplicating disc-to-disc, but I agree it didn't take long for the 'professional' pirates to copy and distribute the game."

In that regard, at least, the dongle was a success - though few remember it that way, and its reputation as a grand anti-piracy folly endures to this day. "The extent to which it worked is debatable," Bracey continued. "But at least we tried. In the history of my career at Ocean, Robocop 3 and the dongle were a pretty minor issue and it puzzles me why people seem to attach so much significance to it. It really wasn't that important."

Even with the hackers and crackers, this was still mostly the sort of domestic piracy that only required a disc burner and some programming knowledge to pull off. Most Amiga games could still be copied by a home user with widely available public domain programs like XCopy, and at worst they'd come up against something like Rob Northen's Copylock, which used a disparity in the read/write capabilities of the floppy drives to create data that could be easily read, but difficult to write to a new disc. Since this was the golden age of the demoscene, there was always some willing hacking crew prepared to break the code and insert their own boastful scrolling message at the start of the game.

Where cheap media such as discs and tapes were concerned, piracy was theoretically within the means of most domestic users. For consoles, piracy was a very different kettle of peg-legged fish. Reproducing knock-off cartridges required, at the very least, rudimentary manufacturing facilities and a steady supply of blank microchips and other components.

Even so, from the NES onwards the Far East was awash in counterfeit carts, often on sale in mainstream shops. Companies such as Spica even produced clones of the NES hardware, and in 1991 Nintendo asked for US assistance in stemming the tide of illegal cartridges pouting out of Taiwan, with many of the components supplied by United Microelectronics Corporation, which was formed and co-owned by the Taiwanese government.

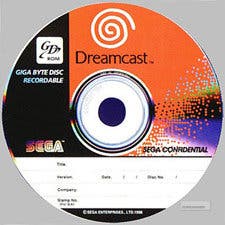

With such rampant piracy, it was strange that Nintendo so doggedly stuck with the expensive and cumbersome cartridge format for the Nintendo 64. Instead it was Sony and SEGA that took the plunge with disc-based consoles, and the associated piracy issues that come with easily writable media. Whereas early computers had to rely on software solutions for their anti-piracy, the unified design of a games console meant that such measures could be built into the hardware.

Legitimate PlayStation CDs, for example, wrote to disc sectors that domestic CD-R burners couldn't access. The fledgling trade in modchips gave gamers a way around the problem, at the cost of their console warranty, while some games could be made to work by propping open the console's lid and loading the first authenticated track of a legitimate disc before swapping to the pirate disc.