BASIC Instinct: A New Golden Age Of UK Development?

How the gaming greats of the '80s are trying to encourage the legends of tomorrow.

BBC Computer 32K

Acorn DFS

BASIC

>_

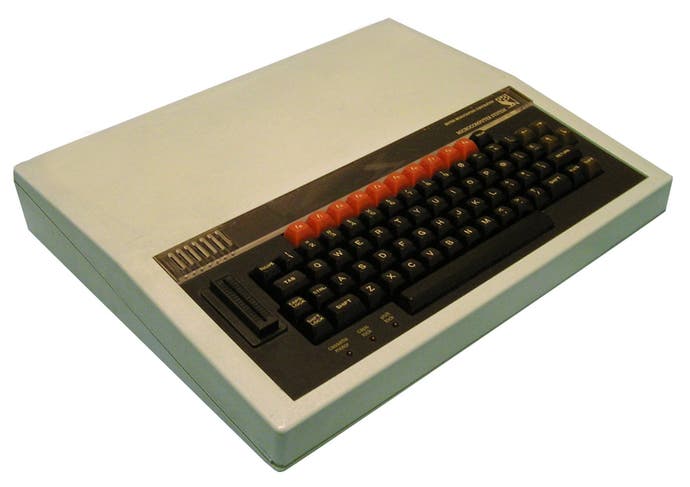

For gamers of a certain age the text of the home screen of a BBC Micro may summon a fair few fond memories. And what those short, white-on-black lines and blinking cursor represented above all was possibility.

Games were only ever a *TAPE and CHAIN "" away (assuming, of course, the tape then actually loaded), but what mattered was that an exciting new world of programming was right there at the user's fingertips, front-and-centre, whenever the machine was switched on.

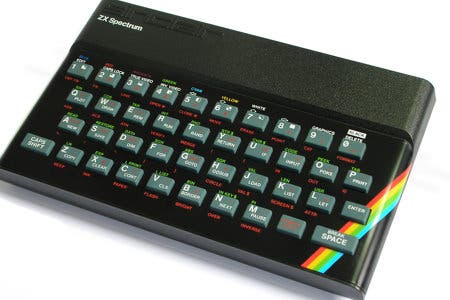

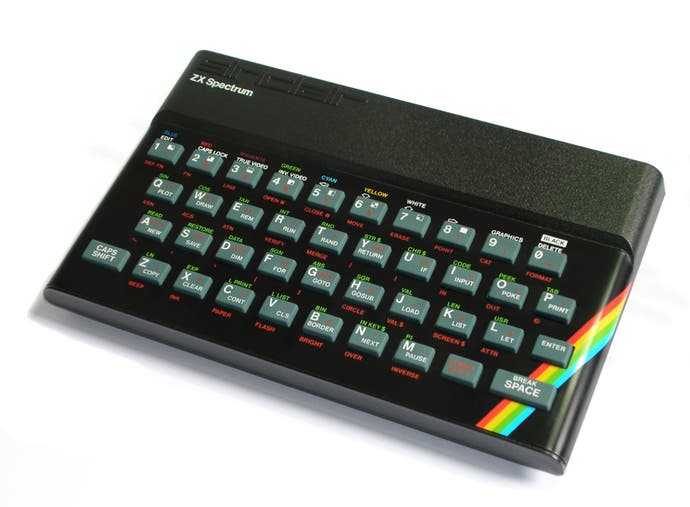

Whether it was the BBC Micro in schools (and, if you were lucky, at home), or a less extravagant model like the dear old Speccy, computers were designed to be messed around with by everyone, with the basic skills to do that taught in schools.

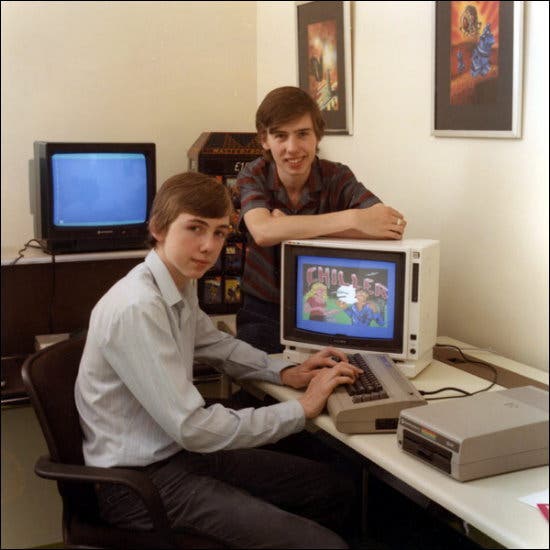

We all know what came next: a thrilling era of UK game making, with names like Molyneux, Braben, Smith, the Stampers and the Darlings flooding the market with all manner of bizarre and often brilliant games.

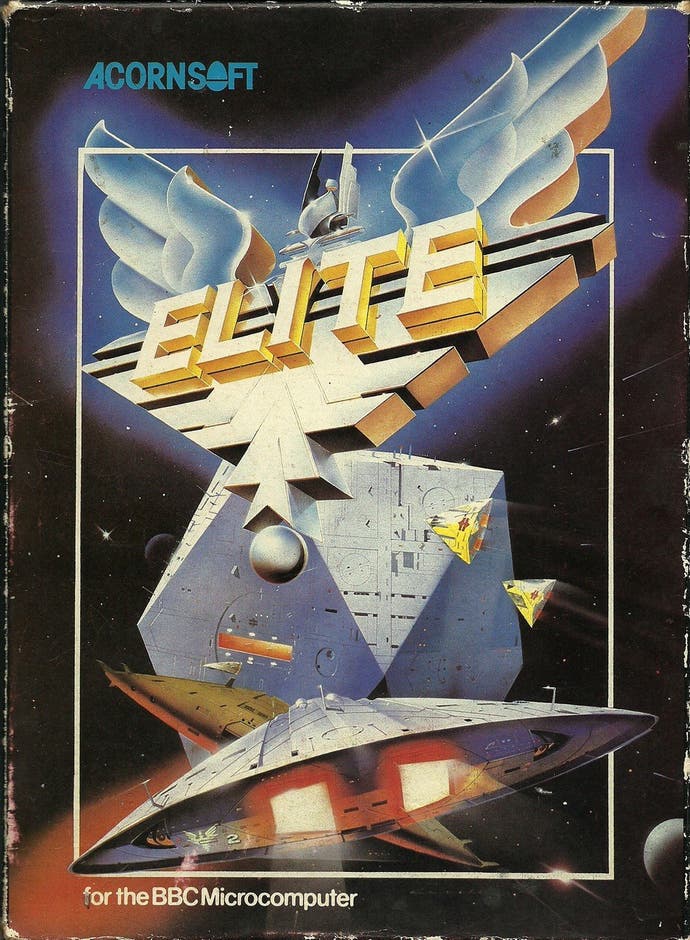

"It was amazingly exciting," acknowledges David Braben, who co-wrote the classic Elite with Ian Bell for BBC Micro while they were still students at Cambridge University. "It felt like the world was your oyster."

These days Braben heads up Frontier Developments in Cambridge, the studio most recently behind the adorable likes of Kinectimals and Disneyland Adventures.

But he's also involved in a technology project that's causing something of a stir, designed to be, in effect, the BBC Micro of the 21st century. And he's hoping that it will help produce the next generation of gaming heroes.

Raspberry Pi is its name: a £20, credit card-sized PC, that went into production earlier this month with the aim of rolling it out to schools by the end of 2012. The question, though, is why is this even required? What went wrong? And what does it say about the state of UK games development?

"The BBC Micro came with everything you needed," says Braben. "Same with the Acorn Atom. Once you got it you could write a program, play it and show it to other people. Programming was quite easy. That's what caused a lot of people to try it."

"I learned at school in Canada," reveals David Darling, who, along with his brother Richard, went on to form top Brit outfit Codemasters in the mid-'80s, bashing out a bevy of classic titles along the way.

Living in Vancouver, age 11, Darling was taught "how to program on a computer that didn't have a keyboard. We had to put stuff in with a card reader, use a pencil and fill in boxes to make a code.

"It became really tedious, so I asked if I could stay after school to use it at night, when a keyboard was available," he adds. And that access was all it took to fire the imagination, inspiring him to start writing his own games.

When the family returned to the UK three years later, his father bought a Commodore Pet for his company, which designed contact lenses, believing work would be easier with a computer.

"He said if we [David and his brother] could program it for him, we could borrow it at the weekend."

Darling's secondary school was "generally encouraging about new technology, but at the time very discouraging about games. I made a game for my coursework - but got a low grade and was told video games were a waste of time." It was ever thus.

The reason Britain churned out so many talented game makers in the '80s, then, was in large part thanks to the straightforward availability of relatively easy-to-program hardware and the teaching of the basics.

"Going through the loft over Christmas, I found that the C64 had programming in the manual," says Braben. "You were expected to know it and encouraged to learn in a friendly way."

"Lessons enabled you to have a good background on different types of storage and different computers," agrees Darling. "It provided a framework to work within - the exciting thing was that it was all new and pioneering."

But, as PCs took over, all that changed, computers became 'locked down' and the seeds of industrial failure were sown.

Braben blames "a generation in government who had no technology representation. None had been in industry or had technology expertise. They thought technology was great, but they thought ICT was technology. Even though technology is in the title, it's no such thing: it's how to use Microsoft Office and Windows."

ICT - information and communications technology - is the dragon the games industry has been seeking to slay for years. "It's like learning how to read without teaching you how to write," notes Braben, quoting Eidos exec Ian Livingstone - the man whose tireless campaigning on the issue has, quite against the odds and in a remarkable sequence of events, apparently vanquished Britsoft's scholastic nemesis.

"At Eidos we're in a situation where we have no UK development anymore," Livingstone laments. "Tomb Raider is made in California, Hitman in Denmark, Deus Ex in Montreal. Wearing my patriotic hat, that's not great since we're so good at making games.

"We have a history of making brilliant games - because we had the BBC Micro as the cornerstone of computing, and the Spectrum as an affordable, programmable computer in the home. Given our heritage, to me it's shocking that we were going backwards."

The UK, as is well documented, has been steadily sliding down the international development league table, having its best talent snatched by the likes of Canada, where development is backed by generous tax incentives. And while there is still good, homegrown talent coming through, there isn't nearly enough of it.

In his role as chair of the sector skills council, Livingstone knew these problems all too well. It was, says the man often styled as the 'Father of Lara', "depressingly clear that our universities were sadly failing - not all, but many - of the students on their courses.

"Many prospectuses that purported to be guides for getting a career in games industry were nothing more than media studios courses with media crossed out and games inserted". Clearly, something needed to be done. But what happened next surprised everybody.

A momentous 18-month campaign was kick-started with the commissioning of a Government report by Culture Minister Ed Vaizey, which became the influential Livingstone-Hope Next Gen report, going on to win the public backing of Google chairman Eric Schmidt, turn the Prime Minister's head and, ultimately, secure this month's dramatic announcement by Education Secretary Michael Gove that "harmful and dull" ICT would be scrapped, to be replaced by computer science in schools starting this September. Phew.

Livingstone backs away from taking too much credit, stressing the "fantastically huge team effort - a lot of people putting in a lot of time." One of those people is Andy Payne, chairman of UKIE, the UK industry trade association.

"Why this has happened is there's been a coalition of industries, key players within them, coming together and saying technology is our future," he insists. "It's never happened before. We'd always seen ourselves as just the games industry - proudly so, but not able to effect changes as well.

"What the Government has done is realise the opportunity for young people to be creative - but also recognised the risk of not having workforce that can play to that tune, understanding the risk of hanging around while rest of world skills up".

So, while Gove's plans are a massive victory for the games industry-led campaign, as Payne notes, "the work starts here".

Either way, one hopes there would have been a few champagne corks popping in Cambridge as the headquarters of the 'Raspberry Revolution' received the news.

"We have every hope Raspberry Pi will end up in massive numbers in education," says Braben.

The key to Raspberry Pi is not just its ultra-low price - it's also about giving kids a machine they can screw up on without ruining it. As Braben points out: "I've made a living from it, but it's quite hard to program a PC now - and quite easy to stop it working!

"We're making the machine itself robust and easy to reset: press reset and you'll be back playing with it. It will give the confidence that you can do things and in the worst case press reset and start again." Just like the 'Break' key on a BBC Micro, in fact.

The devices being soldered together in a factory in Asia right now are what Braben calls the "developer version". "We're not ready to put into classrooms yet". The "consumer version" will come later this year.

"What we want to do between the developer and consumer versions is to wrap that so it becomes easy to use like a BBC Micro." Which may even mean, he gleefully notes, "that BBC BASIC would work".

UKIE's Payne thinks Raspberry Pi is "highly important". But with over 22,000 schools in the UK, "we need a lot of them, and big tech companies to step up to the plate to help the Government fund this stuff."

In a neat irony, while all this has been going on in the background, the '80s era of the bedroom programmer has returned anyway, through the proliferation of smartphone devs and indie micro-studios.

One such operation is Kwalee, David Darling's new startup based in Leamingston Spa. Darling left Codemasters in 2007 and now sees traditional console development, with "hundreds of people on teams and millions of units of stock", as "quite old fashioned now you can do it all digitally".

He admits it was a "conscious decision" to return to his roots of small-scale development. "It's attractive because doing games for mobile devices delivered digitally means you can have small teams." Kwalee's first multiplayer-focused game is due in "the next two or three months".

But while the opportunities may be there, the talent is harder to find. "There is a general skills shortage in the industry," admits Darling. "We're recruiting for programmers at the moment - it's hard."

While initiatives like the return of computer science in schools and Raspberry Pi will make a difference, there's no magic wand and everyone involved admits the impact won't truly be felt for years. But it's a start.

"It's perfect timing," reckons Livingstone. "There's never been a better opportunity for people to produce and publish their own content - small, agile teams, self -taught, putting out stuff for global audiences."

"It's the 10, 11 year-olds now that need inspiration," says Payne. "By 20 they're creating world beating products," he adds, stressing that it's also vital to get the under-10s "focused on science, maths and art" now by making sure they realise that these are the skills that create the games they play.

Darling agrees that Raspberry Pi has "got to be a good thing," but cautions: "To get kids excited now they have to be interested in what's new nowadays. Most people are driven by the apps they can actually use. My sister's boy is five and mad on Minecraft - there has to be something you can do with Raspberry Pi that excites them."

So, in 2022, can we realistically expect to be hailing a thriving new generation of Molyneuxs, Brabens and Darlings, as they emerge heroically at the other end, armed with the world-beating knowledge to realise their daring digital dreams?

"I certainly hope so," says Livingstone. "We are the most creative nation in world. We're good at high tech, but we haven't been allowing our children the opportunities to realise their potential. If we fast-track from now I don't see any reason why we can't be one of leading nations again."

"I think there's a good chance," suggests Braben, to produce "not just great game makers, but great technologists".

"We've seen the first generation of standalone computers," he explains. "The second generation is now: mobile devices, like smartphones. The third generation, which we've not really seen yet, is ubiquitous computing, where computers disappear altogether into other devices - and someone will make the devices that take advantage of that."

Exciting times, then, and a road ahead that could indeed lead to a bright, brilliant future for Britsoft. But there's a lot of work to be done to get there. And the one thing the games industry doesn't have, of course, is a 'Break' key.