Battle for Azeroth recaptures something World of Warcraft has long missed

Divide and rule.

"Not my warchief," says the goblin rogue who is moonwalking around impatiently as we listen to some dialogue. We're playing The Battle for Lordaeron, the scenario which introduces Battle for Azeroth, World of Warcraft's latest and seventh expansion. He's talking about Sylvanas Windrunner, undead elf, queen of the Forsaken, and current Warchief of the Horde, one of WOW's two quarrelsome player factions.

I'm not on a role-playing server, so it's pretty rare for players to offer this kind of in-character comment on what's going on. In fact, these days it's rare for players to ever use the /say command to talk to other players in their immediate vicinity - they tend to stick to general or private chat channels, keeping their heads down as they get sucked individually along the game's slickly grooved paths of progression. What's needled this goblin so much he had to speak up?

It's about recent events in World of Warcraft's storyline - but it also harks back 14 years to the game's launch, and even earlier, to vital decisions Blizzard made in its making.

Sylvanas is announcing her plan to break an Alliance siege of Forsaken hometown the Undercity by using Blight, a horrific chemical weapon. But this isn't even her greatest outrage of the last few weeks. During the build-up to the release of the new expansion, she torched the World Tree and sacked Darnassus, home of the Night Elves, in a preemptive strike. Horde players reacted strongly. Though their faction is composed largely of monstrous-looking races like orcs and trolls, Horde players are not the bad guys; a loose alliance of cosmic immigrants and dispossessed freaks, they see themselves as the hardscrabble resistance to the self-righteous Alliance. ("I just realised: we're the Rebels and they're the Empire," a Horde brother-in-arms said to me during the early days of the game.) They consider themselves honourable, and Sylvanas' actions have left many Horde players feeling about her the way many Americans currently feel about Donald Trump. Not my warchief indeed.

This plotting has been hotly debated online. Sylvanas is the fourth Horde Warchief since the game started and the second to "go bad", and players are starting to feel their allegiances have been railroaded just to move the game's storyline forward. Blizzard developers will tell you that the arguments about it have been just as fierce in-house. But the strength of feeling is, in itself, remarkable. One of World of Warcraft's greatest achievements has always been the intense identification players have with their faction. You can roll characters on both sides, and most do, but in your heart of hearts you know where your loyalty lies and you hold the opposing faction in disdain. It's a quasi cultural identity and it creates a powerful bond between player and game. This stuff matters.

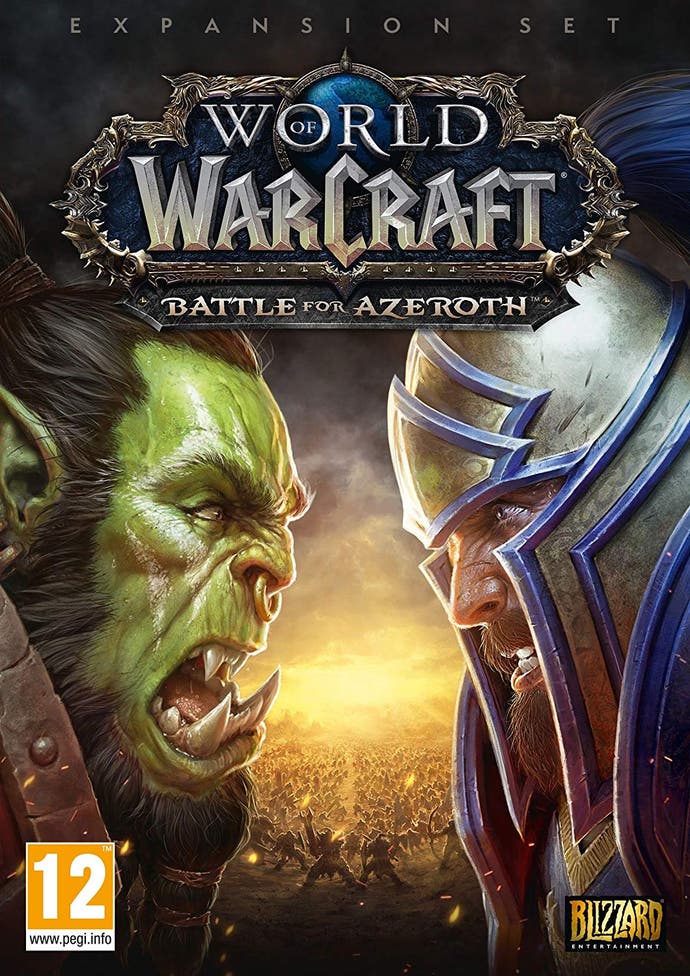

Battle for Azeroth drives straight for this feeling. The entire expansion is organised around intensifying your sense of belonging and stoking the enmity between the Horde and Alliance. It does this in a way that WOW has rarely dared to since launch: by keeping the factions apart.

According to former game director Tom Chilton, the single most contentious issue among WOW's design team ahead of launch was the decision to disallow communication between the two factions. As he once told Eurogamer: "Allen Adham, who was the original lead designer, was very adamant that the split was going ahead, because we needed to break the game into teams... like Dark Age of Camelot had done. Players were split into those teams and they felt like they were a part of something. It automatically meant that you had people who were friendly to you and willing to help you, who you could join up with - and you know who the bad guys were. In Ultima Online, while not having those boundaries was interesting, it was a huge hurdle for players. People didn't feel like part of anything - they didn't know who their friends were, who they were supposed to be fighting against, what they were supposed to do."

It turned out to be a brilliant move. I remember a moment from the game's early days, warily waiting for a late-night ferry alongside an Alliance player. I could tell from this gnome's kit that he was an engineer, like my troll character, and so I felt a kinship with him; but we couldn't talk about it because the /say command would translate our speech into gibberish across factions. So I produced my mechanical squirrel pet, which only engineers could make, and pointed at it. He did the same. Then we spent a happy few minutes demonstrating our silly gizmos to each other before going our separate ways. It was a magical, hands-across-the-divide moment that was only possible because the divide had been placed there. This is why this stuff matters.

The thinking extended throughout the game, right down to its two vast land masses, one of which was dominated by Alliance cities and predominantly Alliance questing zones, with the Horde pushed out to the edges, and vice versa. The game's intense exoticism was heightened further when you knew you were in unfriendly territory. And yet, despite occasional gestures in this direction - such as Warlords of Draenor's divided starting areas - the game's six expansions have mostly sought to bring Horde and Alliance players together against a common threat, and several attempts to make "world PVP" (mass player battles out in the open world) work have fallen flat. Players' sense of faction pride has always remained a great strength of the game, but one that Blizzard seldom played to.

Battle for Azeroth changes that. The storyline is, for the first time in the game's history, explicitly centred on the factions' struggle. On his defeat in the last expansion Legion, demon-god Sargeras thrust his sword into the world of Azeroth, which is now 'bleeding' Azerite, a powerful resource that the factions are warring to control. Hence Sylvanas' aggression against Darnassus and the Alliance's retaliation at the Undercity (events which have robbed both factions of their most significant base on the continent dominated by the other, pushing them even further apart). Now each faction has journeyed to new subcontinents in search of allies: the Horde to the ancient troll empire of Zandalar, the Alliance to the seafaring nation of Kul Tiras. Their quests and storylines are entirely separate, and opportunities to set foot on the other faction's new territory are relatively scarce.

This is quite an undertaking, theoretically doubling the amount of levelling content Blizzard has had to make for Battle for Azeroth. It pays off beautifully. When I discovered a small neutral zone by accident and saw Alliance players for the first time, some 15 hours into my time with the expansion, it was a delicious shock. I was reminded of my first sight of an Alliance raid in the Barrens, of how nervy and thrilling it is to be around people who can't understand you and probably want to kill you - even when PVP is turned off. (Anything-goes PVP servers no longer exist in World of Warcraft, but 'war mode' can be toggled on at will, which lifts PVP restrictions, matches you with other bellicose players and grants additional rewards.)

Another benefit of this approach is the most grounded storytelling WOW has seen in a long time. Throughout the game's life, individually strong quest lines have been easy to find - from the elegiac to the satirical, the sublime to the joyously ridiculous. But the bigger picture has often been a smudgy mess. The Warcraft series is overburdened with backstory and expansions like Legion and Warlords of Draenor tied themselves in so many timey-wimey, alternate-reality knots that it became hard for anyone who wasn't deeply invested in the lore to understand or care about what was going on. Long-gone villains started to pop up with the regularity of special guest stars on a vintage sitcom, canned applause in tow.

Battle for Azeroth, however, takes place very much in the present tense (although the return of Jaina Proudmoore to a full-throated role will carry some weight for Alliance lore scholars). The stakes are clear and the story is told from first principles. Zandalar is a delightful portrait of a decadent kingdom, squabbling and inward-looking, overshadowed by its former glories. It's gorgeous, too, with great golden ziggurats standing amid jungle, swamp and desert, lit by lurid low sun. The capital city of Zuldazar is one of the most awe-inspiring environments in WOW: a sprawling metropolis that works simultaneously as a hub for social activity, services and downtime, like any of the major cities, and as an adventuring zone in its own right, bustling with intrigue and tension. WOW has never seen the like before; even Legion's Suramar was just a preview.

Thematically, Battle for Azeroth is as fresh and direct as World of Warcraft has been since its youth. Mechanically and structurally the game is also in rude health, although it was Warlords of Draenor and Legion which made the great strides that got it here. Legion especially: the sixth expansion introduced game-changing innovations that ushered in, if not a new golden age, then at least a glorious Indian summer for WOW, so it's neither surprising nor disappointing that its successor follows its template closely.

World Quests, the brilliant endless questing carousel based on Diablo 3's Adventure Mode, return at the endgame, while the progress and customisation offered by Legion's Artifact weapons is back in a mutated, slightly less successful form. The weapons, which were specific to your class specialisation, are replaced by an Artifact necklace which in turn powers up a whole range of armour pieces, each with its own set of unlockable traits. This system is broader but less deep than Legion's; it doesn't homogenise the look of players as much, but the rather basic traits don't have as meaningful an impact on your playstyle. Legion's focus on the character classes wasn't as cleanly irresistible a hook as the new expansion's faction war, but it did engage more closely with WOW's game systems.

That said, faction war has inspired a couple of intriguing new game modes. I haven't yet had a chance to try the Island Expedition resource-gathering scenarios, which pit your team of three against three from the opposing faction, although I love the idea that the AI opponents at lower difficulties serve as training wheels for the real, player-controlled thing - and I respect the attempt to blend WOW's largely siloed PVP and PVE experiences. The showpiece Warfronts are 20-player base-building raids that promise to deliver, at long last, one of WOW's founding goals: to let players experience Warcraft 3 battles at ground level. The first Warfront won't be available for another few weeks, however.

Regardless, it's a delight to find, in Battle for Azeroth, a 14-year-old game rediscovering something about itself that it had almost forgotten and recapturing the tribal frisson that helped make its early days so unforgettable. It feels good to have those fires of loyalty and buccaneering rivalry stoked once more. For the Horde!

(Not for Sylvanas, though.)