BEEFER: Saving old games from the attic

Spelltower forever.

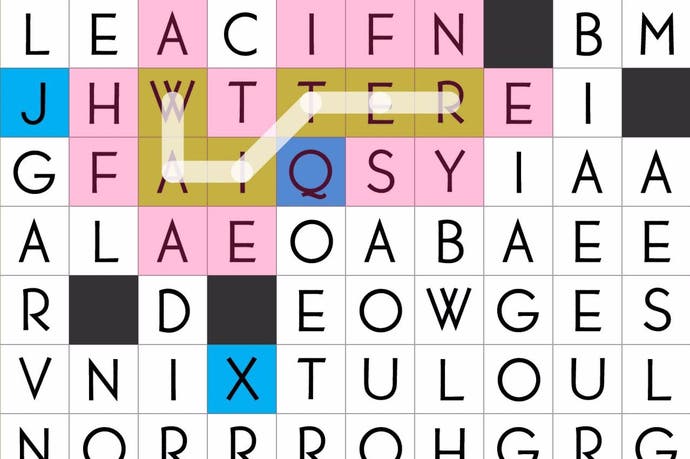

For 30 seconds this morning, the most important word in gaming was BEEFER. That's if you happened to be on the number 27, racing along the south coast towards Brighton, anyway, and if you were the man sat next to me on the upper deck, who was trying to play BEEFER in a game of Spelltower. Seriously, the stars had almost aligned for this man: he had the letters he wanted and he had a workable layout. What he did not have, and I am very sorry to report this, was access to a universe in which BEEFER appears in the dictionary.

He had tenacity, too. As I got off at my stop, he was still trying to get it to work. And why not? BEEFER has clearly touched many lives. It has certainly made me think - and not just thoughts like: Hey! BEEFER would be a great term for the guy at a party who clears the room with loud and intricate explanations of his exercise regime. BEEFER has made me think about Spelltower: about games, and about the new ways that old games now have of hanging around.

Spelltower is not old. A Google search suggests that it came out at some point in 2011: an ingenious puzzling riff that used an American newspaper aesthetic and some devious countdown rules to make the hunt for words in a constantly evolving grid surprisingly tense and punishing. 2011 for games, though, feels like an aeon ago - or at least it should, because four years has traditionally been a very long time in this world. It is long enough for many titles - and a lot of hardware - to begin the tech equivalent of the dusty march into the distance that the dinosaurs make in The Rite of Spring. You know: first tech "gathers dust", and then, it's "consigned to the attic." This process has been around so long, we now have terminology for it.

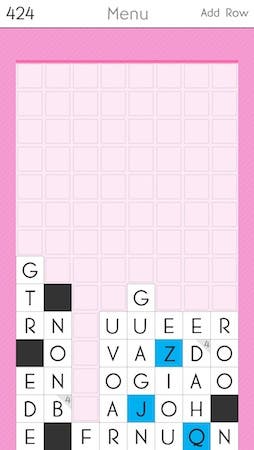

There is no reason that this has to be the case, of course. Most committed gamers keep a few old machines and a bunch of cherished titles to hand, and Steam may well ensure that PC games are around for a really long time, should you wish them to be. But there is something about smartphone gaming that still feels a bit new in this regard. How often do you see somebody playing a Game Boy on the bus? I never see that, and I get the bus into Brighton every day, with the driver deftly skirting Penny Farthings and Hoverboards. Meanwhile, it's not just possible to see Spelltower being played in the wild so long after its release, it's entirely possible for you to have it with you too, in your pocket, along with Drop7, Solipskier, and Hero Academy.

Book shops - thoughts to the family - have this idea of core stock, of key titles that are always relevant, and so will always be on the shelves. (Just knowing about core stock can be a kick in the teeth, of course, as it is when you race into Waterstones on your way to a friend's birthday and discover that some suit has decided it's time to retire Carter Beats the Devil.) Tech doesn't really have this, and in too many ways we still lump games together with toasters and Digital SLRs rather than paperbacks and DVDs. With these smartphones, though, old games can be within reach a lot longer - although Apple and Google will inevitably introduce new models and operating systems from time to time which will kill a bunch of them off for no good reason, and Zynga is ceaselessly trying to destroy Drop7. For a while, then, with this stuff and with Steam, we have a form of core stock in games, and it's quite nice to see strangers on the commute making use of it. It's quite nice to think of games living on and having useful lives long after the reviews have stopped coming in and the sales have ceased to have an impact, with no chance of anybody mentioning dust or the attic.

It's enough to make you want to download Trism all over again. Man: that was one BEEFER game.