Before I Forget review - a vital addition to neurological art

A story about love and memory.

The literature of neurology is rich and varied, yet it is almost always concerned with understanding. It's concerned with the quest for understanding, hard-earned and often incomplete, and with the value of understanding, and the fundamental differences it can make. This is not surprising. Right near the top of the list of needs, I would argue, a neurology patient needs to be understood - by doctors and nurses, and by the bureaucracy of social care and welfare. Also, a neurology patient often needs to be understood by strangers, the people encountered in shops and when boarding buses. And by family. All patients want to be understood - we all want to be understood in sickness and in health. But neurology is often a buried landscape, strange things fizzing and flickering in the shadows. It is filled with private symptoms and internal events that require interpretation. Too many aspects cannot be easily shared.

A case in point: in 2015, dementia overtook heart disease and stroke as the UK's biggest cause of death. It looms large in our world, and yet I have sometimes wondered if I genuinely understand what it is at all. And then: for an hour last week - a vital, strangely thrilling hour - I got a bit closer to a basic comprehension. All thanks to the literature of neurology - in this case a video game.

Dementia is the broad term for a constellation of different conditions affecting the brain. Commonly, it's shorthand for that illness where you sometimes forget your keys, what you did with the mail, what your own face looks like, what your children are called and who they are. But it's also more than that, if that is possible. More than forgetting, dementia can be a panoramic and degenerative experience that involves everything from hallucinations to periods of clarity. When the brain is attacked, and I am paraphrasing the neurologist Dr Allan Ropper here, you have to understand this one thing - the person is in the brain.

Before I Forget understands this very clearly. This is a game that wants to open out dementia, to make us all understand it as much as we can. What an ambition. What a beautiful, frightening, noble thing to try with games.

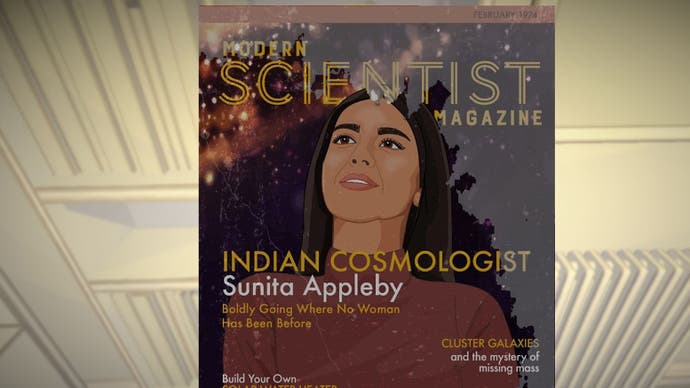

To do this, Before I Forget drops you into the world of Sunita, a woman with early-onset dementia. The game takes place in her house, a sweep of clean, airy rooms that nonetheless have the potential to upend your expectations and jumble you around. It also drops you into her head, a place where the past and even the present are liable to flicker out and only reappear with prompting - via a photograph in a frame, a Post-it on the fridge, the details swimming back into view as you move in and really focus. And so: you wander around the place and investigate objects here and there and slowly start to piece things together.

I don't want to spoil too much of the story, but what emerges over the course of an hour is in part a narrative of compromise - compromise in terms of small things and very big things. To be ill is often to be compromised in some crucial way, and Before I Forget is very, very sharp when it comes to making this apparent. Doors do not lead where you want them to. Corridors are placed out of use by things beyond your control. A ringing phone is an alarming, disconcerting event - you can't wait for it to end. Crucial things are almost comprehended but hover just outside of consciousness. Sometimes - for one very stressful sequence - you know exactly what to do but you just can't make it happen. This is neurological disease perfectly encapsulated.

The more I played, the more it became apparent that stoical, funny, brilliantly intelligent Sunita exhibits something that could be characterised as distrust of self. Where did this distrust come from? Play on. Over time, and unexpectedly, the gaping pettiness of dementia starts to make itself visible in Sunita's world, along with a sense of how those various instances of pettiness can pull together in devastating ways and have profound impacts.

I notice now that in writing this I'm focusing on the disease, which is the classic mistake. And it's one the game itself doesn't make. Before I Forget always puts Sunita's illness in the context of a life richly lived, a life of achievement and travel and love and insight. By the end of the game I understood exactly who Sunita was as well as what was happening to her. I admire this game almost above all else for understanding that a neurological illness, even a fatal one, does not have to become the dominant story of a person's existence.

Talking about his own neurological disease, Parkinson's, Michael J. Fox wrote that in some ways his diagnosis has been a gift, but it's the gift "that keeps on taking". You can see some of that in Before I Forget - the way an object, an umbrella or a postcard or a map of the heavens, will bring the distant past back into the present with a sudden overwhelming force. A victory, but maybe a frightening one. Even then it fades, and it hints at all the other things that have already faded along with it. It's a reminder of an important thing about this game: Before I Forget can't actually make you forget. And I think its designers appreciate that, as a result, part of what it's trying to do is impossible.

I don't mean this as a criticism. Quite the opposite. One of the most moving aspects of this game is the realisation that very basic aspects of dementia cannot be known without being experienced. To put it another way, we can follow the game from discovery to discovery, but we cannot share the process of undiscovering that upends so much of Sunita's daily life. But now - and this is extremely valuable - I feel like I actually understand that, at least.