Beneath A Steel Sky - Remastered

Charles Cecil on resurrecting the classic adventure.

Speaking of the 1980s, we ask Charles to describe that period for him as a game-maker, and the emergence of the genre in which he'd make his name. "I wrote my first game in 1981. At the time I was studying mechanical engineering on a university course sponsored by Ford. Through that sponsorship program I met Richard Turner, a coder who invited me to make some games with him. I'd spend two weeks writing a game and then Richard would take two weeks to code it. The moment the game was finished we'd phone up WH Smith, the biggest videogame retailer at the time, and convince them to place an order for 5000 copies. Then we'd called up the local printer, ask them to ship a batch of covers down to the tape duplication company in Banbury and then they would ship the packaged games to WH Smith. It would be three phone calls and then we'd have £40-50,000 in the bank. We were essentially students. It was insane."

While Cecil is eager to point out that the pair was turning out good products at the time, he's the first to admit that their success owed a lot to timing. "We were extremely fortunate to be making games at that particular point in history. As soon as the big American companies got involved they blew us out of the water and it became clear just how fortunate we'd been. After that I worked for US Gold and then Activision. After a while Activision started running into some difficulties and told me that I would have to move onto a part-time contract. I asked them if I could start up my own development studio, they agreed and Revolution was born."

Two days a week Cecil worked his day-job at Activison, while the other three were spent setting up the new company. These early days were unglamorous. "Our premises were above a fruit shop in Hull. It was so cold. We had a gas heater that spat out terrible fumes. In the middle of winter we either closed the window and turned the gas off, or closed the window and turned the gas on. Our coders wore fingerless gloves to type." But far from resenting this Dickensian set-up, Cecil believes it provided the kind of environment in which start-ups flourish. "I think that too much money can be a dangerous thing for a start-up developer. You look at the companies that start with a bang and they normally go with a bang."

Mirrorsoft, Robert Maxwell's emerging videogame publishing company, supported Revolution's first game. "Sean Brennan [who now works for Bethesda] was deputy managing director at Mirrorsoft and was one of the key people in convincing me to set up Revolution. He assured me that they'd support us if we set up a studio and was true to his word. Our first game was codenamed, Vengeance, which is obviously a s***ty name. But as development drew to a close we couldn't settle on anything we liked. In the end I gave Alison Beasley, head of Mirrorsoft marketing at the time, a list of possible titles and asked her to choose between them. Of course, she picked out the one joke entry I added to the bottom of the list: Lure of the Temptress." When I explained that there was neither any luring nor a temptress in the game she suggested we add them sharpish. So we rewrote the story and characters to fit the name, adding a month to development time."

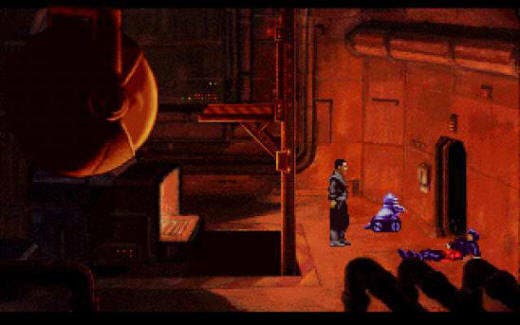

Following the success of Lure of the Temptress, Revolution started work on Beneath A Steel Sky, a game that came about via collaboration with Dave Gibbons, an artist most famous for his work with Alan Moore on the seminal graphic novel, Watchmen. "I knew Dave because, while at Activison, we'd been in discussions to license a Watchmen game. I loved the idea of collaborating with someone who was so experienced and talented within a different medium, so convinced him to come and work with us. We were now in a slightly more upmarket, salubrious office in Hull, and Dave would come up via train to work on the story with us. He designed all of the characters and then drew the backgrounds in pencil." These pencil sketches were then coloured by one of Gibbons' friends, Les Pace, before being scanned in and animated by the team, giving the game its unique look.