BioShock 2 is the underrated human heart of the BioShock trilogy

Still held in Rapture tension.

Editor's note: To mark the announcement of the BioShock Collection - okay, the confirmation of the BioShock Collection after more leaks than even the tattiest corner of Rapture - we're returning to Richard Cobbett's brilliant retrospective on BioShock 2, first published in April 2013.

BioShock 2 rarely gets the respect it deserves, though it's not too difficult to see why. It was a sequel nobody was really crying out for, even before we got our first glimpse at Columbia - a return to a city whose story felt comprehensively finished, and one looking more like a retread than a revolution.

There's some truth in that, especially in terms of combat and graphical style - though BioShock 2 does refine much of the original experience. There's more to it than raw mechanics though, and while it's far from one of the best sequels ever made, giving it a chance reveals it as one of the smartest. Its moment of genius? New creative director Jordan "Fort Frolic" Thomas (an odd middle name, admittedly...) and team taking the original game and ruthlessly inverting all its themes. Same city, new perspective.

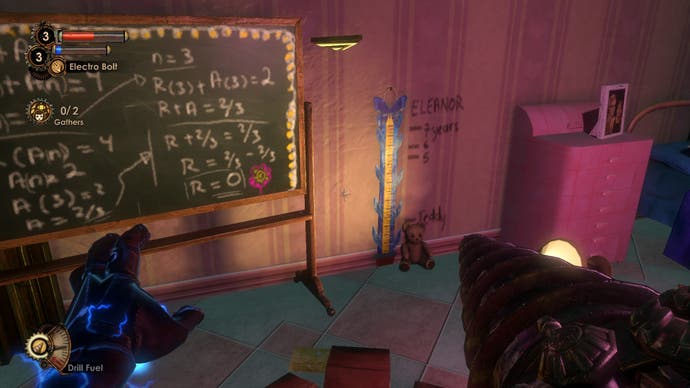

The new main character establishes the tonal shift. In BioShock you'd been a squishy man, but now you're an elite Big Daddy called Subject Delta, with a drill-arm capable of carving through splicers with impunity. BioShock's focus was primarily on the elites of Rapture, while BioShock 2 spends its time walking amongst the poor. The villain's philosophy is collectivism, mirroring Ryan's objectivism, taken to the point where altruistic selflessness turns into arrogant disinterest in the individual. The first game assumed ignorance of Rapture, while the sequel requests a decent level of familiarity. It was also primarily a story of what had happened, whereas BioShock 2 is about what happens next - about Rapture's final legacy to the world.

The list goes on, but its most important element is that where BioShock was ultimately the story of a city, BioShock 2 is the story of its people - and in particular, a father and daughter relationship. On the surface - or to be more exact, several fathoms under it - that might sound very familiar. Like so much of BioShock 2 though, the style makes it different.

Under Ken Levine, both original BioShock and BioShock Infinite offer effective emotional moments. They're a colder flavour of emotion though - Nolanesque, if you will - coming more from the head than the heart. Even ignoring the fancy speeches that inevitably accompany them, their reason is always to illustrate authorial points. That doesn't make them bad - many of them are very effective indeed - but even a hammer with big sad eyes painted on its handle will always unmistakably be a tool.

BioShock 2 offers a more nuanced take. Take Augustus Sinclair, its Fontaine equivalent - a ruthless businessman who makes no secret of his plan to pick Rapture clean for profit. By audiologs and his own free admission, he's a career bastard and proud of it. Even so, when you go up against an elderly rival called Grace Holloway who's both actively trying to kill you and previously gave him a bloody nose by kicking him out of his own hotel, he makes a point of reminding you that her beef with you at least is based on a misunderstanding rather than malice, and goes so far as to non-sarcastically call you a bigger man than him if you spare her.

Ruthless as he is, he's not a cardboard cutout. He's also one of the few BioShock characters with the self-awareness to know when it's time to drop the philosophy textbooks and have a human response to what fate has in store. None of this makes him a 'good' guy, but they do make him more than just another ideology given flesh.

It's a similar story with Grace herself. She's an antagonist, but in no way a villain - never mind one of BioShock's trademark mad howlers. Her backstory is sympathetic, and her allegiance to her genuinely nasty faction leader misguided but utterly understandable. In her surface life she was a black singer who escaped to Rapture in the hope of a better life, only to find utopia far from living up to the hype. Blackballed for singing songs criticising the administration, and her lover disappeared by Andrew Ryan during his purges, she ended up alone and barely scraping by in the poorest part of town.

Then Sofia Lamb entered her life. Sofia is BioShock 2's big villain; a psychiatrist who expertly built up a cult of personality around herself before being arrested, conveniently imprisoned during the events of the city's fall, and wiped from Rapture's history. Before this happened, Grace was given the honour of becoming her daughter Eleanor's guardian - the kind of responsibility she craved, and the child she desperately wanted but had previously been unable to have due to being barren. Instead, she soon found this last shot of happiness stolen by one of Lamb's enemies, and Eleanor turned into a Little Sister pair-bonded with Delta. When Grace tried to intervene, Delta broke her jaw. All that tragedy is wrapped up tight in a now decade old grudge. It's not exactly undeserved.

These are the stories of BioShock 2 - of people so desperate that they give their love and loyalty to a woman so cold that she thinks of herself as less of a mother than her daughter's "intellectual progenitor", and who have fallen into or simply never climbed out of the poverty of a shantytown built around a pumping station.

Yet despite this, and other downer moments, something about BioShock 2 breaks away from being depressing - moments like Sinclair's humanity or sparing Grace speaking to an optimism that's often missing in Levine's characters. It being a darker world makes acts of kindness count all the more, without the series' standard cynical view that everyone is just a scrap of power away from corruption. In BioShock, that extended to assuming the worst of the player for harvesting Little Sisters. In BioShock Infinite... well, let's not go into spoilers!

There's one comparison with Infinite that has to be made though, and it's Eleanor Lamb - Sofia's daughter, focus of her ultimate plan, and the connection between her and Delta. Lamb of Columbia, meet Lamb of Rapture, both deified within and trapped inside their own gilded cages. Elizabeth obviously has technology and budget and screen-time, but replaying BioShock 2, I'd argue that Eleanor is actually the better of the two leading ladies. Certainly, she's the most interesting, even without the power to rip holes in reality.

While not fully revealed until late in the game, BioShock 2 is a tale of fatherhood, Eleanor having been deprogrammed after her time as a Little Sister but still retaining her childhood bond to Subject Delta. In one of many nice touches, you get to choose how - or indeed, if - you want this to be reciprocated, and why you're chasing her. If it's to help a damsel in distress, fine. If it's simply that Delta can't survive without her nearby, that works fine too. Even Eleanor admits she's chosen to believe the best from her adopted father figure, who doesn't have the vocal chords to tell her if she's right.

Where Elizabeth can be flat though, and is reliant on Booker and other men in her life for protection and purpose, Eleanor is her own woman. It's her rebellious streak as a child that kickstarts the story. Even captive, years later, she takes a direct hand in her own rescue - first by slipping Delta supplies via the Little Sisters, and then tooling up as an armoured Big Sister to take responsibility for both her mother and her future. She's a superb example of a strong, active female character, whose non-magical achievements really leave Elizabeth in the dust.

What's really great though is her malleable character arc. As with BioShock, there's a moral question over harvesting the Little Sisters for Adam - and again, one neutered by you being fine whatever you do, but never mind - with three other specific moral decisions to make. Handling Grace is the first. Two others face a similar choice.

These are important not because of direct payoff, but because Eleanor spends the game using your decisions to calibrate her moral compass. Harvest too many Little Sisters for power, and get ready for a scene where Eleanor obliterates entire dormitories of them for the same. Play nice though, and she picks up on that compassion - just as being inconsistent confuses her. There are several endings, and most are tearjerkers - but like the rest of the game, handled with subtlety. Sofia Lamb for instance can either survive Rapture or not, but whether she survives via Eleanor's pity or a spiteful desire to have her live as a failure rejected and discarded even by her own daughter is down to your 'parenting'. (There's more to it, of course, but I don't want to spoil everything.)

So, with all this good stuff, why did BioShock 2 fizzle on release, and why did many people who bought it walk off disappointed early on? Sadly, there are a few reasons, starting with a truly terrible opening hour that plays like a direct-to-video sequel to BioShock and even copies it beat-for-beat in a few irritating places. The combat and enemies are pretty much the same, with the most obvious differences being a simpler hacking system and a tedious new mechanic involving guarding Little Sisters while they harvest Adam from corpses.

Thankfully, after the tutorials are done you hit Ryan Amusements. This is a theme park supposedly dedicated to Rapture founder Andrew Ryan's dreams of a place where the elite need not fear the parasite and all that other familiar rhetoric, but now a living monument to his hypocrisy. It's a wonderful piece of design, where dioramas depicting exactly the rules that would see Rapture turn from heaven to hell are depicted in fine style. From there, BioShock 2 only improves - through the poverty of Pauper's Drop to the red light district of Siren's Alley and beyond, including a perspective shift that isn't a plot twist exactly, but is still BioShock 2's big Would You Kindly moment.

The result certainly isn't a story that will cast any extra light on BioShock Infinite, or which meshes seamlessly with the original game. In particular, while Sofia Lamb's absence from the first game is explained, it's explained in a way that asks you to meet it half way - that obviously the reason she wasn't in it was that she didn't exist yet, but roll with it, okay? The limited technology and mechanics also can't pull off the illusion that there's now an organised splicer society in Rapture, unless you add some self-justifications about their mental state and everyone simply being on high alert.

Those are however small prices to pay for a game that may not advance some great BioShock canon, but still stands as a great way to round off your view of Rapture - a world that always felt like a designed dystopia more than a failed city suddenly converted into a much more plausible place.

Picking it up also means a second chance to grab Minerva's Den; the excellent DLC that closes out Tanenbaum's otherwise oddly brushed off storyline and draws the final line under BioShock's underwater era. That's well worth playing, even if it's still annoyingly pricey, but don't let anyone tell you it 'saved' BioShock 2. The basic chance to return to Rapture is more than worth your time on its own - assuming you're willing to give it an hour to find itself.