Blue Toad Murder Files: The Mysteries of Little Riddle

Croak and dagger.

Poke around Relentless Software's website and you can make a strong argument that the developer has spent the last few years playing it safe. But it has played it so well in the process. The Buzz! series is always at its strongest when it's in the gentle, assured hands of its real parents, and it's as much for that reason as any that Blue Toad Murder Files arrives propelled by waves of critical interest apparently disproportionate to its status as a family mystery series.

That series begins with a pair of downloadable episodes released on PS3 today, which cost £6.29 individually or £9.99 for the pair. You and up to three friends select a suitable member of the Blue Toad Detective Agency to represent yourselves and then arrive by train in the quaint English country town of Little Riddle, where almost immediately you find yourself on the trail of a naughty murderer.

You certainly know it's a quaint country town, too, because the station master has mutton chops and immediately complains about a disagreement over the tea room, and because every sound effect is a duck quacking or the butcher's preferred refrain ("scum!"), and because the narrator's ponderous delivery is continually enlivened by a "puffing conveyance", "vittles" or a "muuuurdeeeer".

At times it's very much caribou nibbling the hoops (and believe me when I tell you there is no greater praise), but as you set about interrogating the town's charmingly stereotypical inhabitants you realise this is more than a convenient hook. The station master has mutton chops because there should always be something silly to look at, the ducks quack between screens because there should be no dead air, and the narrator's glacial loquacity is designed to let you enjoy these things and keep up with the unfolding mystery at the same time.

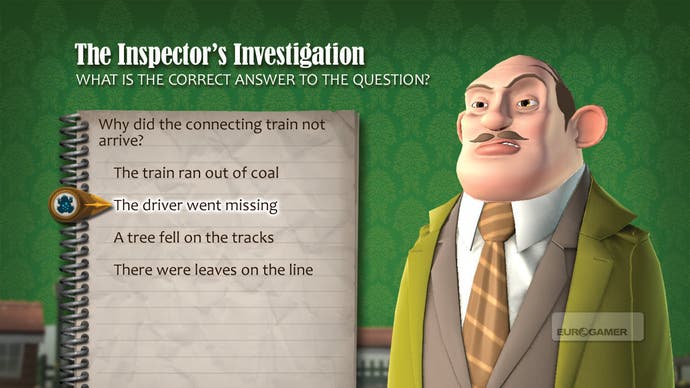

Because make no mistake, you're on the clock. 12 puzzles lie ahead of your group in each episode, along with the occasional brief catch-up quiz to make sure you're paying attention, and at the end you're expected to identify the perpetrator and confront him or her with your evidence.

Each puzzle begins with an interrogation cut-scene where the narrator voices your concerns for you, and while the subject of your inquiries responds you get to admire the peculiar objects lying in the background, or the way his chin flaps as he speaks. Or sometimes, as with the vicar and his delightful intonation in episode two, you just stare open-mouthed as he sends up the Church of England (because, you know, it worked so well for Resistance: Fall of Man).

Then you get a puzzle. These range from logic teasers about moving sacks around or organising bees around flowers, to maths and word puzzles where you crack basic codes and work out how many guests are in a hotel, along with a few based on visual observation under difficult (often rotating) circumstances.

Technically you are competing with your fellow players, earning medals based on how quickly you answer and how many attempts it takes, but the nature of the puzzles means that people usually muck in. Even when the pad isn't in your hand you can't help solving them as you look on, and when it is then the gentle pressure of wanting to get a gold medal and get it right without mistakes is amplified by the presence of an audience. Have they already worked out which of the windmill sails is different? Have they deciphered the constable's message? Have I got that sum right?