Born Under A Bad Sign

A history of good videogame villains.

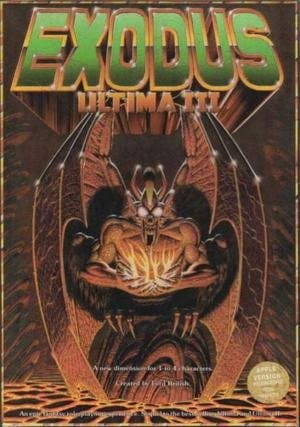

Richard Garriott realised this back in 1983, having just completed Ultima III: Exodus. He noted the moral absurdity present in the vast majority of games of the day (including his own), where players were heroes because the instruction manual said they were, and villains were villains because that's who the players were told to kill. And in order to reach that "villain", players would murder, pillage, and plunder everything in punching range, while their enemy meanwhile did nothing particularly reprehensible other than maybe leer at a handmaiden or two while listening to Tears for Fears.

Garriott's first step in a multi-tiered solution was Ultima IV: Quest of the Avatar, which stripped the Ultima formula of any discernible villain, and instead focused on monitoring the player's adherence to Garriott's moral code, also known as the eight virtues of Honesty, Compassion, Valour, Justice, Honour, Sacrifice, Spirituality and Humility.

Subsequent Ultima games reintroduced proper villains, but this time Garriott strove to make them actively subvert and flout the virtue system introduced in Quest of the Avatar. In doing so, he was able to craft the series' most engaging storylines.

Ultima V: Warriors of Destiny explored themes of absolutism (where the virtues were legally implemented with fascistic rigour), Ultima VI: The False Prophet touched on racism and intolerance, and Garriott's finest achievement thus far, Ultima VII: The Black Gate, was an unabashed, open-ended account of his feelings about The Church of Scientology and the Devil in Sonny Bono. (Sad footnote: the final two Ultimas are probably more instructive of the perils of aligning oneself with a corporate meganaut who doesn't understand your work schedule than anything more life-changing.)

The greatest examples of videogame villainy - and I continue to refer to the in-game rather than Stefan Eriksson variety - released since Ultima have predicated on its teachings. Consider Fallout: the Vault Dweller's arch-nemesis, The Master/Richard Moreau, is revealed to the player in tantalising snippets as the game's true main quest is gradually revealed. When you finally meet him beneath his cathedral - and be forewarned, Fallout virgins: his appearance and voice remain with you longer than you might wish - it never feels like pointless cheese included so you have a big monster to fight at the end. In fact, it's quite possible to convince Moreau to see the flaws in his own nefarious logic, thereby persuading him to destroy himself and his master plan.

It's an absolutely beautiful use of the full range of character stats available in an RPG, and, to my knowledge, it's only ever been repeated with such - forgive me - skill and class in Planescape: Torment.

If GURPS' only meaning to you is as the sound you might make after a few too many Slippery Nipples, perhaps you'd prefer to talk about Resident Evil: Nemesis. The titular Nemesis, Capcom's eyeball-shouldered mutant, wasn't exactly a work of majestic literary perspiacity, but you know what? He had the sense to actually chase Jill Valentine throughout her jaunt in Raccoon City, often appearing at the most inopportune (and genuinely unscripted) moments. As a result, the monster earned the player's fear and hatred almost entirely emergently.

As with the above examples, a videogame's villain should ideally become one with the game's mechanics, whatever they may be. One of my favourite uses of interactive villainy, the various "wolves" of Tale of Tales' The Path, made their presence known throughout your chosen character's forays into the woods outside grandma's house.