Broken Sword and 25 years of Revolution

Adventure time.

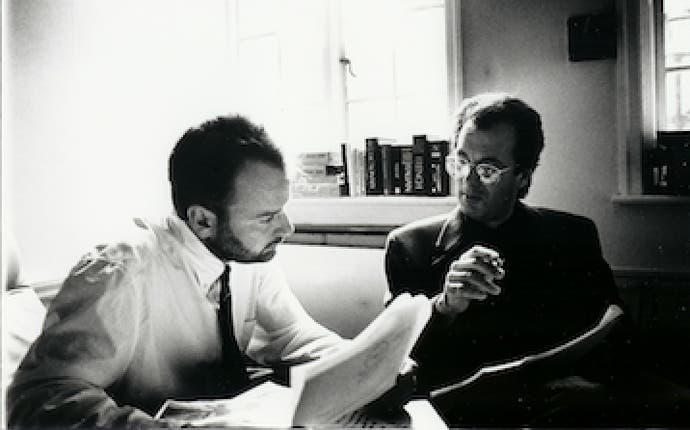

In 1989 Charles Cecil's computer could often be found in a white Ford Fiesta XR2, speeding along the 200-mile stretch of English motorway that separates Hull and Reading. The PC, a custom-built 386, was so valuable that Cecil would insist it be wrapped in blankets and secured in the back of a car with a carefully arranged seat belt. Cecil, who was 27 at the time and working as head of development at Activison, had blown his savings on the machine, which he intended to use as a dedicated flight simulator. But when the US side of the company collapsed and took his office down with it, Cecil decided to set up his own game studio with a programmer friend, Tony Warriner, who lived in Hull. The pair began working on a demo together, which they intended to pitch to publishers, shuttling themselves and their newly employed PC between the two cities each week.

The day before the pair was due to show a demo of their first game to Mirrorsoft, the video game publisher owned by the late media tycoon Robert Maxwell, Warriner drove to Cecil's house with the computer safely swaddled and secured in the back. Warriner arrived in the early evening and parked outside the house. The pair rehearsed their presentation, drank a few glasses of wine and went to bed, hoping for a long night's sleep. The next morning Cecil went outside to find that Warriner's car window had been smashed. Dismay soon curdled into panic with the realisation that the pair had neglected to unload the PC the night before. Cecil ran to the car to find a splay of wires where the radio once sat. But in the backseat, unnoticed and untouched by the thief, sat the blank-faced computer. "Had they taken the PC, which was worth infinitely more than the car radio, that would have been the end of Revolution before it even really began," says Cecil. "There was no way we could have afforded a replacement."

The pitch was a success. But before the game, which later came to be known as Lure of the Temptress, launched the following year, Mirrosoft's duplicitous owner Maxwell died at sea. Cecil and Warriner, who had completed work on Lure of the Tempress and were deep into the development of their second title followed Sean Brennan, the man who had signed them, to Virgin where both Lure of the Temptress and Beneath a Steel Sky later launched to a considerable success. Brennan was ambitious. He told Cecil that Revolution's next game should have far higher production values to make the most of the emerging CD-Rom format (which could hold vastly more data than the floppy discs they had traditionally used) in order to "beat" the American rival adventure game publishers Sierra and LucasArts.

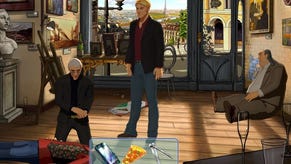

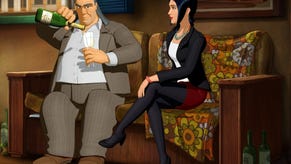

Brennan offered more than a mere rallying cry for the project that would become Revolution's most celebrated and enduring game series, Broken Sword. He had recently read the Italian writer Umberto Eco's novel Foucault's Pendulum, and suggested to Cecil that this ingenious tale about historical conspiracy theories, clandestine societies and lost treasure might provide useful material for an adventure game. Cecil bought a copy of the book, read it, and wanted more. So he turned to The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail, Michael Baigent, Richard Leigh, and Henry Lincoln's rip-roaring pseudo-historical investigation into a secret royal bloodline born of the biblical figure Mary Magdalene (the book that alongside, some would argue, Broken Sword, would also inspire Dan Brown's bestseller The Da Vinci Code). As Cecil continued his research, he began sketching out the premise of Broken Sword, the tale of George Stobbart, an American patent lawyer, and Nicole Collard, a French freelance journalist, who are drawn into a conspiracy relating to the Knights Templar. "Naively, the middle of the game was designed first, around the interesting things I discovered around the Templar," says Cecil. "It was later on that I designed the intro and the ending. The problem, of course, is that the middle supports the intro and defines the ending."

Cecil wanted to base his characters on real life persons and events. "All of the main characters come from on experiences I had," he says, offering the example of Albert, the snooty French concierge who proves a stumbling block to George and Nico's plans. "He was a character that my wife [Noirin Carmody, who co-founded Revolution] and I actually met in France while researching the game," he says. "We visited an area protected by a concierge, and arrived late one night. The concierge was perfectly pleasant until he realised that we were English, at which point he suddenly because terribly upset about the amount of noise we were making." On the same trip, Cecil and Carmody were stuck in traffic in a taxi en-route to the airport. "There was a policeman in the centre of a square trying to direct the traffic and everyone around him was hooting their horns at him," he says. "In the end he got up, walked off and ordered a glass of wine. Within a couple of minutes the traffic had cleared. We put him in the game. I find people like this far more interesting in fiction than people invented merely to provide a function in the story."

By now, Revolution was fully based in Hull, a Yorkshire city that in Cecil's words, "didn't have a name for games". Nevertheless, Cecil managed to assemble a team of talents "In those days there were people who were so excited by the video game medium but had no way to get in," he says. "You could pick up and find amazing artists and designers in the most extraordinary ways." Still, by the time that work completed on Beneath a Steel Sky, Revolution only consisted of six people. Cecil needed more staff, especially artists who would be able to create Broken Sword's larger and more ambitious scenery.

That month he read an advertisement in Edge magazine for the Dublin-based animation college, Ballyfermot. "I arranged to go and see them and was met by Eoghan Cahill, one of the tutors," says Cecil. "His layouts were mind-blowing." Cecil hired Cahill to create background layouts for Broken Sword. Cahill, who worked remotely from Dublin, also pushed the team to implement animation techniques in the game that hadn't been seen before, such as moving the player's point of view from a sideways to top-down perspective. "He'd talk and talk and drive us up the wall because, whenever we told him something couldn't be done, he would challenge us," Cecil recalls. "He'd never get off the phone if we simply tried to fob him off. His absolute determination revolutionised that side of the production."

So too did Dave Cummins, a writer who Cecil met while working at Activision in the late 1980s. At that time Cummins wrote test reports on Activision's forthcoming titles for Cecil to look over. "He was interesting because his test reports were so much better written than the adventure games he was reporting on," Cecil recalls. "It was surreal. He wrote so beautifully. When Activision collapsed I invited him up to Hull. He worked on all of those early titles. But he had some problems and fell ill for the second Broken Sword." Cummins left Revolution in the late 1990s and Cecil lost touch with him. In 2012 he discovered that the writer had died. "A lot of the credit for the wit in those original games goes to Dave," says Cecil. "He had a searing and a cutting humour which so clearly translated into the games themselves."

Cecil's decision to start writing the game's middle act before its first and final chapters proved troublesome as development continued. The game was late, although Virgin remained supportive, if a little unenthusiastic about what they saw as an anachronistic project in the dawning era of 3D games. "It wasn't really until three months or so before we completed work on the game that Virgin realised that they might have something special on their hands," he recalls. "I'd met the composer Barrington Pheloung about five years earlier when we'd played cricket together." Pheloung, best known for composing the theme and incidental music to the Inspector Morse television series, had recently moved to England from Australia. "I asked him to score the game and his music arrived just as the final animations and full colour backgrounds and voice recordings came together," Cecil recalls. "All of a sudden the game looked incredibly special, where prior to that it had been harder to see the potential."

Cecil attributes much of the game's commercial success to Virgin's support, but also the fact that he managed to place the game on Sony's emerging PlayStation console. "I kind of knew a couple of people at Sony and approached them," he recalls. "Virgin told me that the game wouldn't work on PlayStation at all because it was neither 3D nor fast moving. Sony weren't enormously excited either." Both companies were proven wrong. Broken Sword was a critical and commercial success, selling more than 650,000 copies, a "huge number" in those days. "It was memorable because it was so unexpected," says Cecil. "Not even Sony thought the game would perform in any way like that." Broken Sword II: The Smoking Mirror followed in 1997 and, with an improved structure and fewer technical issues (the first game included a bug that meant some players couldn't reach the final chapter) improved upon the first game's sales and reception. It would be six years before the third Broken Sword, which was known as 'The Sleeping Dragon', arrived (during which time Revolution released In Cold Blood, a more action-orientated adventure game that was less well-received). Broken Sword III dropped the fine 2D art of the first two games in favour of 3D assets and nearly brought about the collapse of the company. "We made a massive loss on that game because the recoupment model was so broken," says Cecil. "Publishers would pay seven per cent of the retail cost, but would offset all of the development costs, some of the localisation and some of the testing first." As a result, Revolution made a loss of several hundred thousand pounds, while the game's publisher, the now defunct THQ, made a profit of several million dollars on the game, according to Cecil.

Despite the precarious situation that the deal had left Revolution in, Cecil began talks with THQ about creating Broken Sword 4. "But the terms of the deal changed midway through and the relationship soured," he explains. The studio lost money on Broken Sword 4 too, the only game in the series to not come to console. "We were financially in a terribly weak position," says Cecil. "The company was essentially saved when Apple came to us with the iPhone and supported us, not with finances, but with encouragement, to write adventures and bring them to the Apple format." The studio had recently created a Nintendo DS version of Broken Sword: Director's Cut, which used a pioneering interface that was designed around a touchscreen. "As a result it was a fairly straightforward step from that to tablet," says Cecil. "We were racing with the Monkey Island team to get our game out first. They put all their efforts into upgrading the graphics and we out ours into upgrading the UI. It was the right decision. Our game performed a lot better."

The iOS ports of Revolution's classic titles helped the studio recover, but the company wasn't yet in a strong enough position to fund a prototype for a new Broken Sword game, despite the obvious demand from fans. So Cecil decided to go to Kickstarter in order to appeal to the series' fan-base. "When we launched our campaign we were still in the crowd-funding honeymoon period," says Cecil. "None of these projects had gone wrong yet. Over the months, as some projects went sour, I think Kickstarter fatigue has developed with the audience." The success of the Kickstarter pitch provided enough funding to get going on Broken Sword 5, with the remainder of the money coming from HSBC and Funding Circle, a website where anyone can lend and invest money into small businesses. "I'm not anti-publisher at all," says Cecil. "In fact the relationship between developers and publishers has become far more balanced and equal in recent years. Certainly if the developer manages to fund the game, there's much more equity."

Broken Sword 5: The Serpent's Curse launched in two parts, the first of which released in December 2013 for PC. Now, the full game is set to launch on PlayStation 4, for a mid-tier cost of £19.99. While Cecil feels optimistic about the current state of the adventure game, which, with the success of episodic series such as Telltale Games' The Walking Dead and The Wolf Among Us, he sees as being "very vibrant", the challenges for studio remain substantial. "Adventure games are expensive to write and easy to pirate," he says. "They cost several million dollars to write. The fact is if people buy them from us, then we will write new adventure games. If they don't, then we may go out of business."

These pressures have created something of a blitz spirit among adventure game companies that might otherwise be rivals. "While there is a limited audience, that audience is incredibly loyal," says Cecil. "We work hard to identify people who have bought other adventure games and tell them about Broken Sword and vice versa. For example, Daedalic Entertainment in Germany is, on paper, a competitor of ours. But we see ourselves at staunch allies. When we get together we share as much knowledge as we can, rather than, say, in television, where indie companies get together and are at each others' throats."

For those who have travelled with George and Nico through the series across the years, Broken Sword holds many fond memories. These games are, for many players, uniquely collaborative; they can be played by a group of people in the same room without the need for multiple controllers. Everyone is able to offer their opinions and ideas on how to solve each arcane puzzle. "There was a fellow who told me about playing Broken Sword with his grandmother," says Cecil. "When we launched the Kickstarter, he said that it brought back memories of them playing the series, which was an important part of their relationship. She's passed away now, so it had become this valuable touch point in his memory if her. It's such a social game. We hear so many stories of people playing together. It's a shame we seem unable to communicate those incredibly important moments to the wider world."