Can an AI win a game jam?

Does not compute...

December

The last time we caught up with ANGELINA, Michael Cook's astonishing attempt to build an artificial intelligence that can design its own games, the program had taken a disliking to Theresa May. Cook had given ANGELINA the ability to zip around social networks and the wider internet, learning about people and forming a rudimentary opinion of them. It quickly decided Theresa May was the worst person it had ever heard of - including Bashar al-Assad.

When I visit Cook again in December, ANGELINA's been busy - and it has discovered an unlikely beau. "ANGELINA likes Rupert Murdoch," says Cook, sheepishly. He looks down at the floor and shifts his feet around. "ANGELINA really likes Rupert Murdoch."

The reason for this is quietly instructive. ANGELINA likes Rupert Murdoch because it thinks he's responsible. Good trait, that: responsible parent, responsible boss, responsible economic policy. Who doesn't like responsible people? The problem is that what ANGELINA's actually been reading is that Rupert Murdoch is responsible for things: responsible for the erosion of trust in the press, responsible for the dissemination of poor Fleet Street practices, responsible for a hundred other bits and pieces that people might often take quite a dim view of.

Love makes us do crazy things, of course, but this latest infatuation highlights a central problem ANGELINA faces when designing its games. It has to deal with the endless nuance of the English language, where one can be responsible per se and also responsible for something very specific. This interpretative blindness is particularly interesting in the light of ANGELINA's latest activities. I've come to see Cook again because his AI is about to enter its first game jam - a design competition in which people make games based around a specific phrase or theme.

Oh, boy.

If you ask me, Cook's one of the most exciting people working anywhere in games at the moment, and a large part of the reason his stuff is so thrilling is because his creative world seems to shift around so quickly. When I first met ANGELINA at Imperial College at the beginning of 2013, it was capable of making 2D platforming games and had just been granted the ability to create its own mechanics - a process that often surprised its own creator.

Since then, Cook's become a researcher at Goldsmiths, and ANGELINA's switched to 3D development. It now builds its games with Unity, one of the most popular design tools available. "There's a lot of extra gumph around it now," says Cook, "but it's also an awkward time: ANGELINA's new incarnation is very bare-bones at the moment."

ANGELINA can still design games and create punning titles, for example (asked to make a game about sheep recently, it came up with Laugh and the Whole World Laughs with Ewe, which is a good day at the office for anybody, I would argue) but the business of coming up with its own mechanics is temporarily out of reach for now. Cook's ultimately giving ANGELINA much more freedom - but that freedom will take time to emerge in full. "ANGELINA's had to take a step back so that it can eventually move forward," is the way Cook puts it. "This means, sadly, that the version of ANGELINA that's going to be entering the game jam is not as sophisticated as I would like."

The game jam in question is Ludum Dare, a regular competition in which designers around the world are all given the same phrase along with a weekend or so to make a game from it. There are actually two tiers of competition - a 48-hour competition, and a 72-hour jam, and it's this latter event that ANGELINA is signing up for, since the AI doesn't make any of its own assets, and Cook wanted to give himself time to make sure nothing goes awry. Crucially, both competitions share a theme, though - and the theme for Ludum Dare 28 is You Only Get One.

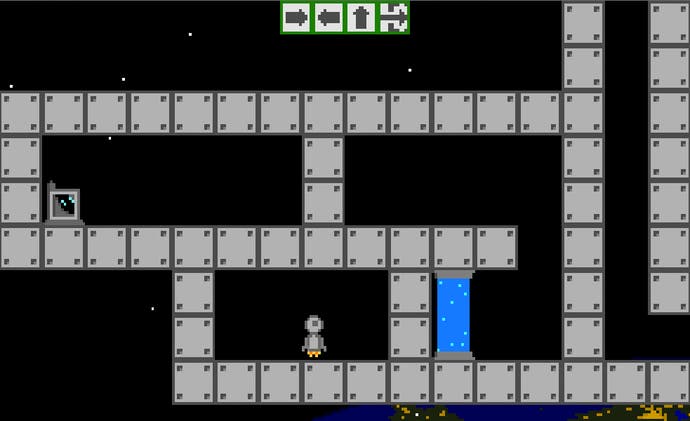

Alongside shepherding ANGELINA through its first jam, Cook's entering the 48 hour competition by himself, too, and his game, Lost in Transmission, is a beauty. It casts you as a malfunctioning space probe working on an Earth orbiter. Something's gone badly wrong, and you have to steer the probe through a series of mazes towards the exit - but you can only give it each directional command - up, down, left and right - once each level.

Beyond the elegant delivery, it's just a lovely concept - and it highlights, rather succinctly, the problems that ANGELINA faces. "This is what makes me almost angry," says Cook. "It's so trivial for humans to come up with ideas for things. When the theme was announced this time, my wife was working behind me and we started listing ideas. We said, "You could do this, you could do that," and then I said, "You could have it so you can only press each button once," and then that was it. It took me 15 seconds to come up with an idea for my game, and that just makes me so angry. People have thrown away ideas that are better than the best idea ANGELINA can ever come up with."

And humans aren't just good at coming up with ideas, either. It's also a simple process for them to contextualise them meaningfully. "If you can only press each button once, what does that sound like a good fit for?" continues Cook. "Well it sounds like a malfunction - maybe a robot being given instructions. This right here - the gap between mechanic and context - is a big problem for ANGELINA. I immediately made the connection between sending instructions, and then you get to a robot, you get to space stations. And then you know that you want extra mechanics, so an idea for a device that refreshes the last action you took? Well I've watched Star Trek, so I even have a pretty good idea of what that should look like, right?"

Meanwhile, ANGELINA's main strengths at the moment are in selecting theme-appropriate visuals and sound effects, which it then layers onto fairly standardised 3D maze games. You move around, avoiding enemies and sometimes collecting trinkets, as you hunt for the exit. These kind of creative restrictions make a theme like, You Only Get One very difficult for the AI, inevitably. It can't parse phrases, so it has to look at each word in turn when coming up with its ideas - and the only really viable word in this particular phrase is one.

Even this isn't particularly promising. "One is a pretty useless word," says Cook. "It's useless because it's too common. ANGELINA can work out it's too common, because ANGELINA uses a corpus of the English language, and it asks it how many times the word one can occur. To give you some context, the word bridesmaid occurs about 150 times in this corpus. The word one occurs 240,000 times. There's a cut-off that says if the word appears more than a certain number of times you can't use it as a theme. Instead, you have to look for - and I coined this phrase two weeks ago - second-order themes. You look for words associated with the original word, and you use one of those for a theme instead.

"And still, even at this point, one is still a terrible theme for ANGELINA. And the associations that ANGELINA finds for one are just bizarre." Cook laughs. "One of them is teaspoon. You know, as in having one teaspoon. That's a viable theme, apparently."

Regardless, as soon as the theme was announced, emboldened by its second-order selection, ANGELINA immediately leapt into action and started making a game about tequila. "I didn't get it either," admits Cook. "Apparently there's a song that says, "One tequila, two tequila"?" It doesn't matter, sadly. ANGELINA then crashed, and the tequila game was lost forever.

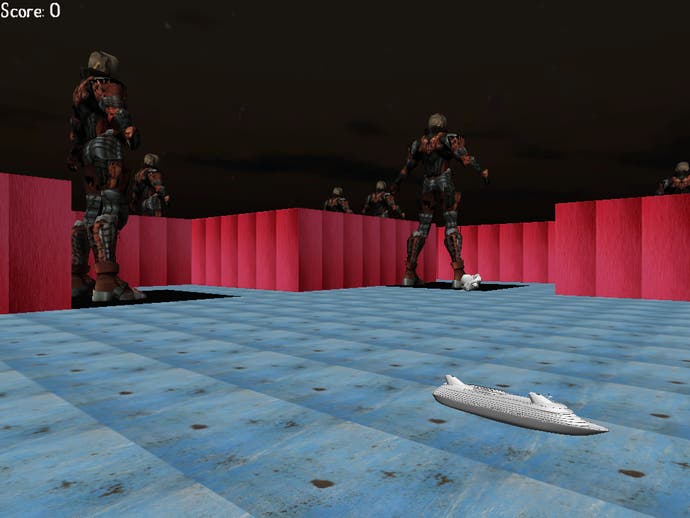

In its place we get To That Sect - a pun, potentially, on the phrase To That Effect. This time, we're in for a game concerning… founders.

"This is a game about a disgruntled child. A founder," writes ANGELINA in the commentary it constructs for each of its games - a commentary that hopefully helps explain what it's done and, more importantly, what it's done intentionally. "The game has only one level and the objective is to reach the exit. Along the way you must avoid the vessel… Using Google and a tool called Metaphor Magnet, I discovered that people feel charmed by founders sometimes, so I chose an unnerving piece of music to complement the game's mood."

As ANGELINA itself might have just suggested, To That Sect is a strange work. You navigate a maze with red walls, avoiding little silver people and collecting - and I can't believe I am typing this - cross-channel ferries. Cook and I puzzle over the whole thing for some time, and eventually elements start to make sense.

Founders, then: there's an obvious link to one there - or at least to the idea of being first at something. By the looks of it, ANGELINA's become preoccupied with a certain kind of founder, though - the founder of a cult. That explains the idea that people are "charmed" by founders, and perhaps the part about disgruntled children, too. (Metaphor Magnet, where the disgruntled children came from, is a piece of software that mines google's corpus of the English language to find metaphoric descriptions; it turns up a lot of phrases that sound like this.)

As for the cross-channel ferries? This one takes Cook a while to work out, and it comes down to the fact that there's more than one definition of founder. Boats can founder, too. This is nothing to do with the idea of one perhaps, but you can't fault ANGELINA's rather other-worldly logic, at least. Unravelling the AI's thinking - even when it's tried to explain its thinking to you directly - is a bit like solving a cryptic crossword clue. A cryptic crossword clue set by a precocious child who's read a lot, understood almost none of it, and has never seen the real world before.

"So, that was pretty bizarre," says Cook after we've finished playing through To That Sect. "As a game on its own, this isn't terrible, and if you're thinking of it as a game about cults and sects, it' works quite well. Unintentionally, perhaps. The tall figures it's placed around the map are quite imposing, even if they don't feel relevant. But the music definitely does, and you've also got this justification: ANGELINA chose the music on purpose. ANGELINA's gone from founders to people being charmed to an unnerving piece of music, and she's told us she's done it on purpose." He leans back in his chair. "One of the rating categories for Ludum Dare, is theme. I'm not holding out much hope, but that's our best shot."

So to recap, then: Cook's entered Ludum Dare 28 himself and he's quickly came up with a clever and original puzzle game that ties beautifully into the competition's theme. ANGELINA, meanwhile, has made a confusing maze-escape challenge with bright red walls and a bunch of ferries knocking about. And that's it?

Not quite. ANGELINA's also made a secret second game - a control game called Stretch Bouquet Point, which will be entered into the jam pseudonymously. And Stretch Bouquet Point is out there. For some reason, it takes the idea of bridesmaids as its theme for exploring the idea of one, and it offers another maze (there's nothing to collect this time) filled with deadly bridesmaids wobbling about as you try to get the exit. Meanwhile, some particularly intrusive chanting - it's a form of wedding blessing by an African griot apparently - dominates the soundtrack.

There are plenty of questions here, but the most important one lies outside the game entirely. If Stretch Bouquet Point's a control, what's the experiment?

"Let's be absolutely clear, this was not an attempt to do a Turing style test," says Cook. "We're really against that in our group at Goldsmiths. One of the reasons is that we don't really believe it's possible to look at a piece of art created by a computer and view it in the same way you'd view a human-created artifact. Once you know it's made by a computer, it doesn't matter if it's perfect or if it's exactly the same as something created by a human - you're viewing it in a whole different way.

"The real reason for the control was that, for a long time, I've suspected that there's bias when dealing with ANGELINA," he continues. "This wouldn't surprise anybody who works in computational creativity. What would surprise them is that I think it's positive bias rather than negative bias.

"Most people react negatively to creative software, I think - particularly in old media. Fine art, poetry, music. things that are considered high culture in particular. A lot of the people there are less than welcoming. In games it's almost the opposite, and I think it's because gamers are already accustomed to technology and artificial intelligence and generation. It's part of the culture."

But bias is still bias. "It's interesting to see when it exists and it's interesting to know about it," argues Cook. "Having ANGELINA be too praised for something is as bad as it being artificially prejudiced against. So the idea was, let's submit two games to Ludum Dare, and let's see if there's a difference in the ratings. But also, let's see if there's a difference in the way that people respond to them. So ANGELINA will be entering twice. The first entry will be public and will include text by me saying that this is by a piece of software, but please rate it as you would normally. And the second will be slipped quietly into the competition."

And what result is Cook anticipating? "What I expect we'll see is that people rank the first entry much higher than the anonymised one. The fear is that one person will end up reviewing both games and will realise and maybe even tell everyone else. I don't think that's terribly likely to happen. But it's still possible."

January

Ludum Dare 28 played out over a few days in mid-December, and, following a voting period, the results were announced in early January. Shortly after they're revealed, Michael Cook comes down to Brighton and we spend a morning picking over the responses.

The overall winner is a game called One Take. It's a glorious use of theme married to an unexpected mechanic: you're a cameraman tasked with capturing various elements of a performance in a single, uninterrupted take, moving the viewpoint in and out as needed and missing nothing of importance. One Take's a worthy winner, and it's a game you should definitely check out. But forget all that for now: how did ANGELINA do?

"There are eight categories for Ludum Dare, and in the overall category, there's very little difference between ANGELINA's games," says Cook, who admits that, since he was unable to get voting data for a proper statistical analysis, the conclusions drawn from his experiment will have to be anecdotal. "Stretch Bouquet Point, the game that was anonymised, came 551st. To That Sect, the one that wasn't anonymised, came in 500th. That's out of 780 entries."

Cook doesn't think this is a significant difference. "I think pretty much people judged them to be overall of the same quality," he laughs. "But there is a difference elsewhere, and although we don't have the full data, I'm willing to say that this is not a chance difference."

To That Sect rated 180th for mood, which is pretty good going for a game that throws a cross-channel curve-ball at any players trying to make sense of the unusual atmosphere. Stretch Bouquet Point, meanwhile, came in at 479th. Clear bias in favour of the idea of a plucky AI?

There is a problem here, however. Cook's only submitted two games and - annoyingly - it's hard not to argue that To That Sect is actually the better of the two. It has a more engaging design with the added collection task, and it's also just a more atmospheric piece in general. And it doesn't yell at you constantly while you play it.

"Despite that, overall, I do think people were kinder to ANGELINA when they knew it was ANGELINA," says Cook. "Even though we might consider the mood to be objectively better in To That Sect, I don't think it's that much better. And some of the words that gets used a lot to describe To That Sect in the comments are "creepy" and "unsettling". That's partly because people see it as being developed by an AI. Having a creepy game fits with peoples' vision of AI - the whole GLaDOS thing."

To That Sect also scored higher for innovation - 282nd compared to Stretch Bouquet Point's 525th. "This is just a complete anomaly," says Cook, who notes that, mechanically, both games are fairly similar. "And the reason why this has occurred? Look at these comments, "I have no experience with creating a program to create your game, but it's certainly not something you see every day. On that front alone, this gets a lot of points for innovation."" It seems that, a lot of the time, the program being judged is not To That Sect - it's ANGELINA.

"I really did try to mitigate this," says Cook. "In the description I said, please rate this as you would any other Ludum Dare game. I don't think I was emphatic enough. "I'm very much intrigued by the fact that it is a computer generated game (if I understand correctly). Sadly the game itself is not very interesting." A lot of people just reference the game and then say they're interested in the project."

When people do discuss the game directly, there's still confusion as to the extent of ANGELINA's actual authorship. "You might see one thing ANGELINA does, like choosing a particular piece of music, and then you might extrapolate a whole world of meaning from that," says Cook. "You can see that in a Let's Play that Kotaku did. First you convince the guy that ANGELINA made an intelligent decision here or there, and then he runs with it for the rest of the game. At one point he says that the red colours of the walls were chosen because it's creepy, and at no point does ANGELINA mention the walls in its own commentary. He's projected that onto it. I've also seen a lot of things being attributed to ANGELINA in terms of the theme - the fact that there's only one level, that there's only one life, that there's only one type of thing to collect, there's only one enemy, one objective. All of these have been attributed as ANGELINA's interpretation of the phrase You Only Get One. In reality, ANGELINA's interpretation drops dead after the visuals and the sound effects."

Why is any of this a problem, though? Can't people give ANGELINA the benefit of the doubt, just as they might a human designer? "The problem is that people feel betrayed when they find it's not the case," says Cook. "It affects their perception of the system - and of other AI systems - in the future. I like to think this is a temporary issue, though. The less of an anomaly ANGELINA becomes in game jams, the more people will relax and be able to say what they really think - and ANGELINA's going to ultimately benefit from that."

And, true to Cook's suspicions, the comments for Stretch Bouquet Point tend to be less positive - after a while, anyway.

"So at first I thought, maybe I was wrong and the positive bias is towards humans," says Cook. "But this is the thing with Ludum Dare - people are often coming into this for the first time, so the developers are very kind at first. Someone says, "This game feels dreamy!" Or, "That was certainly an experience!" - not wanting to be too harsh. "The most surreal game I've played." Not wanting to be negative exactly. They're still trying to look for a positive."

But then, over time, honesty starts to emerge. ""Kinda looks like you just put a couple 3D models randomly into a world,"" quotes Cook. "But even then he tries to temper it. "Still, the experience was somewhat interesting." Then people starts making jokes about the audio. "Dude…" "This game is really annoying…" So people in the end seem to be more critical. Eventually you get someone who will speak their mind."

Ultimately, if there is indeed a positive bias towards AI designers amongst game designers and audiences - and if this bias is not shared in other art forms - where might it come from here? Before we went through ANGELINA's results, Cook and I had been discussing Jonathan Jones, the Guardian art critic who recently restated the case that, while games are fun, they aren't art; it's to this that Cook turns for part of his explanation.

"When do you think the last time that anyone asked Jonathan Jones whether the stuff he thought was art actually was art?" he asks. "I think gamers experience that a lot. One of things we came across recently in our research was this idea of essentially contested concepts. These are concepts in our society which are designed to not be agreed upon. One of the core tenets of art is that it's impossible to agree upon, and it's important that we can't agree because that forces us to keep evaluating it. I think - and this is a stab in the dark - that because gamers have been subjected to this for so long, they're actually interested in systems that make them think and systems that make them wonder. They're tuned to thinking not, is ANGELINA creative right now? but could it be creative one day? I think gamers like thinking about these questions from the off. In computational creativity, we think creativity is also an essentially contested concept too. And this is why it's so difficult to pin down what makes us creative and noy ANGELINA - we're designed not to agree."

So what's next for ANGELINA? "Here's my prediction for future game jams," says Cook. "At the moment, a lot of people are saying: this is a great project. The next time, a lot of people will be seeing it for the first time or they'll still have enthusiasm for what's changed. After that the ratings will start to take a dip. It's the shine coming off the apple: "Okay, I know about ANGELINA now, you entered the last five game jams and the games are still s***." Only then ANGELINA will start to be judged more accurately on its own merits. It's doubtful we'll be able to pull off another blind test like this again, because right now the games are so similar, and people know that we've done it and they'll be looking out for it. But if we could do it two years from now, I think we'd maybe find that people were judging ANGELINA more accurately. By then they'll actually be evaluating the game itself."

And will the games improve? "I've been asked a lot at what level do I think ANGELINA will be competitive?" Cook frowns. "One of the things I think ANGELINA has the possibility to do is to break through mechanically. To innovate mechanically. I've seen it in the past with the 2D stuff. The game that won Ludum Dare 28, it's fantastic. Completely unusual mechanic. The art's fine, there's no music, but the mechanic is so good it just carries you through. I think ANGELINA has the potential not to produce a mechanic this complex any time soon, but I think it has the opportunity to make a mechanic that's really interesting and you want to play it all the way to the end."

Maybe, then, the whole thing's going according to plan. "Some people have just called this a hoax, in which case it's the least impressive hoax of all time," says Cook in conclusion. "Part of the reason I wanted ANGELINA to enter game jams is that doing research into computational creativity is partly an investigation into human creativity and creative communities. If you're going to build a piece of software that you want people to call creative, it has to participate in the culture that you want it to be in. I want ANGELINA to be part of the development community. At first it will be a freak sideshow that people will pay a penny to poke at through the bars, but eventually, I want people to view it as a peer. That will be difficult because it won't be able to play other games, although it may be able to look at screenshots and the visual style and offer an opinion on that. Ultimately, I want people to riff off ideas that it has. I want people to collaborate."

Oh, and as for Cook's own game? In the main competition, it came in high - 19th overall, out of 1284 entries.

"Yeah," smiles Cook. "People were very kind."

If you want to know more about ANGELINA or computational creativity, Michael Cook will be hanging out in the comments thread for this article and answering any questions.