Carrion review - an unforgettable monster chews its way out of a solid Metroidvania

The sweetest Thing.

Discussing the creature design in his gruesome 1982 adaptation of The Thing - a movie which, incidentally, opens with Kurt Russell losing his shit over a computer game - John Carpenter once observed that "I didn't want to end up with a guy in a suit". It's a pitfall many so-called "reverse-horror" games tumble into. You Are The Monster, goes the premise, but does that really mean anything beyond a squelchy skinjob, wrapped around the same old anthropocentric understanding of the world and what it means to act and thrive within it? Even the Alien, horror's apex killer, rarely seems that alien when you slip inside its head in Alien vs Predator, nimble and deadly yet reassuringly bipedal, a pack hunter with binocular vision and the usual appendages.

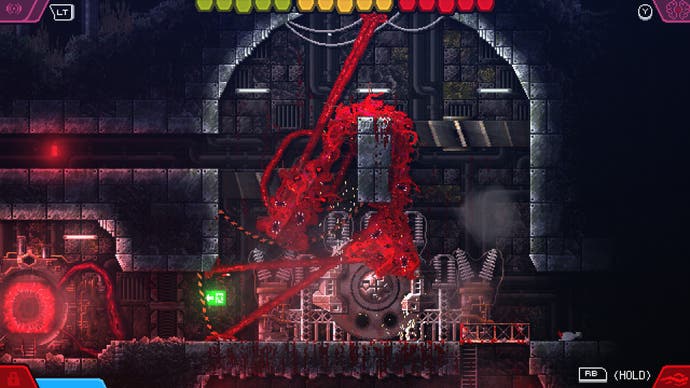

It's to Carrion's great credit, then, that the monster it turns you into is so aggressively inhuman, though I'm not sure the game's wider design quite delivers on its abhorrence. A 2D pixelart game from the aptly titled Phobia Studio, it begins with you exploding from a vacuum tube deep in the bowels of a mysterious laboratory. Screams fill the air as you ricochet around the room, a squirming knot of tentacles snapping wetly in all directions, grabbing onto surfaces and bodies at random. Any human you reel in is devoured in two writhing bites - unlike the Alien, the creature only has a jaw when it needs one - your body swelling and deforming as the victim's biomass becomes your own.

Unleashed upon an underground maze of ransacked temples, nuclear reactors, weapons factories and waste disposal sites, all of civilisation's sins packed into a single, winding ossuary, you must track down other vacuum tubes containing pieces of your flesh, gaining abilities with which to overcome hazards and obstacles in finest Metroidvania tradition. Along the way you'll infest evenly spaced wall fissures to create spawn points, slowly corrupting the architecture till you can burst through a central door into another region. This straightforward campaign framework is the game's big letdown - it gives this avalanche of inchoate flesh a disappointingly human spine. But as games built around ability-gating go, Carrion is solidly wrought, and the monster is revolting enough to keep you locked-on when the puzzles threaten to bore.

In Carpenter's movie, the creature effects consist partly of food: mayonnaise, creamed corn and microwaved bubble gum, washed down with a generous dollop of lube. Perhaps in homage to this, Carrion's creators liken their pet to "meatballs connected by some noodles", a stringy bundle of fanged orbs with canned sprite animations layered on top. The monster is subject to real-time physics - after feeding, I tend to drape it across the geometry like a python digesting a herd of antelope - but it feels unnervingly weightless. It has the surreal agility of a computer cursor, tugging itself through the catacombs at terrible speed, latching automatically onto foreground and background. It changes size to suit the space available, be it a multiple-floor warehouse or a sewer tunnel. It is unconcerned by things like stairs and ladders, though it's often inconvenienced by doors - many of the puzzles involve finding your way around to switches. In combat, its speed and shapelessness allow you to get the drop on soldiers armed with rifles, flamethrowers and portable energy shields, reaching down to grab them one by one or ramming into the group from an unguarded angle.

The monster isn't tough - it loses body mass rapidly when shot and is swiftly consumed by fire, obliging you to race back through the level to the nearest pool of water. This brittleness is an incentive to be cunning, holding up objects as shields or, later, possessing an unaware enemy with a stealthy tendril, but a lot of the time, you can make headway by erupting into view and thrashing around a bit. The trick is not to let them see you coming, with energy shields especially a real nuisance unless you can strike before they're triggered.

The unlockable abilities - some fuelled by sucking electricity from circuit boxes - never quite exceed the awfulness of the monster's base design, but all are amusing to mess around with. Bone lances let you tear the plugs from cisterns or perforate a roomful of grunts in a single, torrential assault. Short-lived armour allows you to pass by exploding harpoon traps unscathed. The additional intrigue here is that the monster must be a certain size to use each ability. You'll often need to scale yourself down to progress, depositing globs of matter in pools of amniotic fluid, so that you can engage your invisibility cloak to slip past a motion sensor. It's easy to regenerate yourself, however - if there are no fresh corpses available, you can squeeze into a spawn point to recover your girth.

Throw in some boss chambers featuring glass-canopied mechs with Gatling guns, and you've got a competent if simplistic Metroidvania. But the appeal of Carrion isn't the satisfaction of matching abilities to the enemy or situation. To be frank, it's the element of torture, the mingled sadism and sympathy you feel as you regard each clutch of human interlopers, wandering about with their weapons up, ears pricked for a ravenous hiss. They're not at home in this place. Oh sure, they have their creature comforts - toilets (with floor vents), soda machines and PCs running what look like other videogames. But the maze wasn't made for them, and they can't move around it like you can. Look at them go, toddling about on their stunted tendrils with their silly gadgets, unaware that just metres beneath their feet, a glorious Cambrian tide of teeth and polyps is slowly encircling the room. See how they plot and scheme, these clever little mammals, fidgety brains always scrambling for a way beyond the skin, into some new reality. Look at them run, shrieking and covering their eyes, as you show them what all that ambition leads to.

It's just a shame that the creature's malevolence is ultimately constrained and somewhat deadened by Carrion the game, though it does end on an engagingly ambiguous note. Later on, it feels like the organism is as much at war with the control scheme as the architecture, growing so vast that you struggle to work out which end is which while navigating fussier bits of geometry. Turning all that terrifying biomass into a means of solving lock-and-key puzzles feels like a betrayal, like revealing the monster for a guy in a suit. Misanthrope that I am, if I could add anything to the game it would be greater texture to its portrayal of human terror: something comparable to Batman: Arkham Asylum, with people growing unhinged as they are preyed upon by the digested and reanimated remnants of their colleagues and friends. Join us, morsels. We are the one flesh. We are everything, in the end.