Cave's Story

Bullet hell in downtown Tokyo.

The company's arcade roots run deep, though, and that's a leap of logic Ichimura isn't prepared to make. "I wouldn't say that it's the 'real' version, or the more authentic version," he says. "We think of it in terms of making two separate versions.

"The arcade is a specific environment in which the customers who play our games don't necessarily have a lot of time to play, so we want to give them the most enjoyment they can have in a short amount of time.

"With the 360 versions, you can play at home, so you can have a much more slow experience, taking the game in over time. We change how we make the games for that home setting - that includes things like co-op modes to play with friends."

The company is still committed to putting the arcade platforms first when it creates new titles. According to Ichimura, parallel development for arcade and console isn't part of the plan. "We've always focused on the arcade first and released on the 360 later," he says firmly. "The arcade will come first for the foreseeable future."

Having broached the topic of creating new titles I'm keen to know how Cave goes about making a new game. The company's offerings feature an extremely broad range of art styles, with the more recent ones even switching between 2D and 3D.

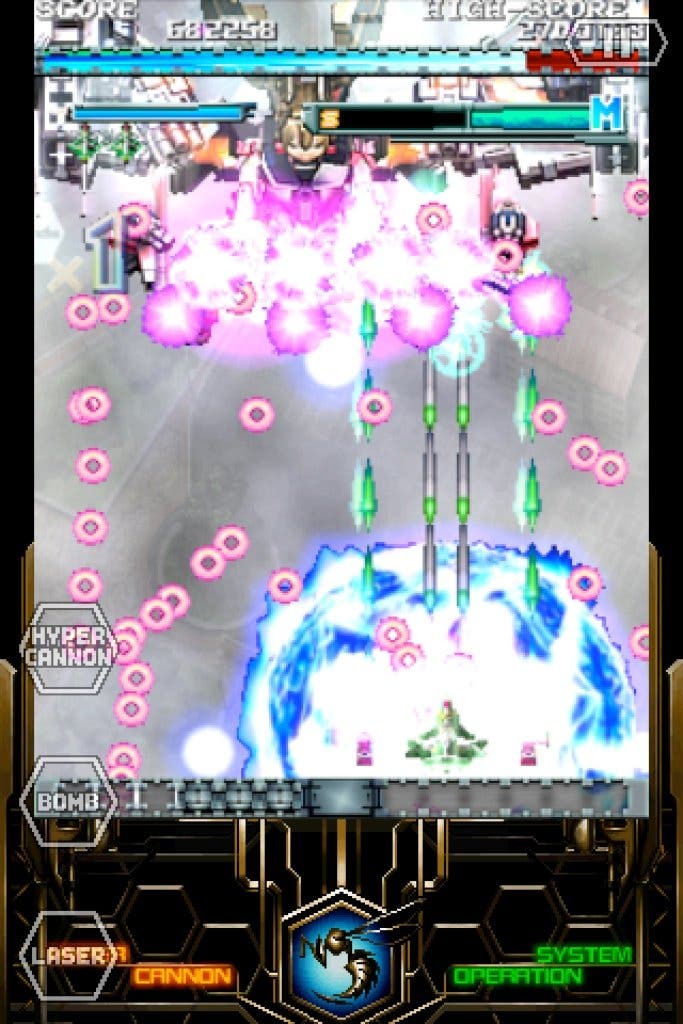

The bullet patterns themselves can be elaborate works of art, swirls and fans of glowing projectiles ranged across the screen like a complex, unfolding orchid, albeit an orchid made out of death and explosions.

It's here, Ichimura tells me, that the games begin - with the art style and the setting. The first thing that's decided on is whether the new title will be 2D or 3D. Then the setting is determined, and an artist goes off to create the masses of illustrations and artwork required for the game.

Only after that do Cave's programmers and designers start talking about the game systems themselves and determining exactly what kind of title they're going to make.

It's an odd way of working, perhaps, but it's been effective for the company for many years. It's tied in with a system of thinking about game design which permeates right into the company's design philosophy, as I discover when I question Ichimura about the bullet patterns in the games.

"The first step [in creating a new bullet pattern] is making the visual of the pattern itself and putting that out there," he says.

"We imagine and experience how the player will react to it, and of course we play it ourselves. If at that point we think that we've actually seen this kind of pattern somewhere before, we stop right there and re-do it.

"If we play it and dodging is a lot of fun, if it's an interesting pattern, we put it to one side and then make multiple patterns to combine into the final bullet pattern in the game."

It seems a little strange that Ichimura is talking about the programmers doing so much of what I'd consider to be design work, and it suddenly strikes me - as it probably should have ten minutes earlier - that he's talking about a really small team.

"Oh, it's basically about seven people," he confirms. "Four designers and three programmers, and to be honest, sometimes I even think that's too many. On top of that, there's a freelance illustrator woking on each project, usually just one person. So I guess that's eight people."

Eight people. And this process takes how long? "Eight or nine months," says Ichimura. "The most time-consuming part is adjusting the game balance at the end."