Chemo and questing in a Super Mario odyssey like no other

Forest of allusion.

Mario often feels like poetry in motion, a cheery pinball in plumber's dungarees forever boinging around brightly-coloured environments. In 1990's Super Mario World, he is specifically on a mission of mercy, criss-crossing Dinosaur Land to save Yoshi's pals from Bowser's malicious forces. In the three decades since its release, strategy guides and walkthroughs have pored over every pixel to unlock Super Mario World's secrets. But no-one has ever written anything about it quite like If All The World And Love Were Young, the debut collection by young Stephen Sexton. This slim volume takes Yoshi's House as the unlikely embarkation point for a dizzying journey into memory, imagination and gut-punch grief.

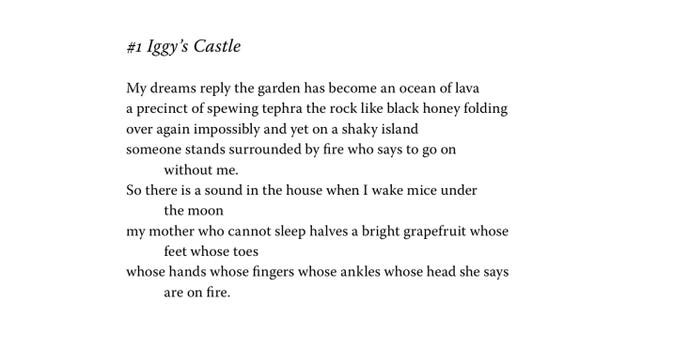

When Sexton was a nine-year-old growing up in Belfast in the mid-1990s, his mother was diagnosed with cancer, triggering a cycle of treatment, convalescence and recurrence that understandably upended the family's usual domestic routines. Like many kids his age, Sexton was playing a lot of Super Nintendo at the time. In an introductory note, he pinpoints the catalyst for If All The World And Love Were Young as a literal snapshot from that era, a photograph Sexton's mother had taken of him hunkered in front of the family's boxy vintage telly, a "cross-legged meditant" engrossed in his console. Who could blame him for looking for escape when everything suddenly seemed so uncertain?

Sexton's 120-page poem cycle is an act of remembrance and expansion that flows from that one image, mapping the precarious period of his mother's illness to advancing through the stages of his favourite game. It's a juxtaposition that has a kernel of absurdity at its heart - fretful meditations on death, delivered in Chocolate Island chunks - but Sexton plays it totally straight. There is nothing as facile as equating ghosts from his past to the spirits floating around the Donut Ghost House or his avatar handily diving into a pipe to flee from reality. Thankfully, there is also no shoutout to Doctor Mario. Instead, his mother's diagnosis is identified in unsettling detail as "cells which split and glitch", requiring exposure to "poison" to try and halt its advance.

Those irresistibly attracted by the sight of a golden Mario coin on a sky-blue Penguin cover will be able to parse most of the Nintendo allusions. Those who aren't so familiar with Super Mario World - perhaps steered towards Sexton's debut by the glowing recommendation of Irish literary sensation Sally Rooney - may lack some of the contextual knowledge but will likely still enjoy the anthropological descriptions of the pixellated overworld, all fire-breathing flora and horned fauna. There is also the appealing notion of readers who have never held a joypad seeking out YouTube playthroughs to see what exactly the deal is with all these wackily-named levels headlining such heartbreaking, impressionistic stanzas.

Before commencing his quest, Sexton preps his audience with an unexpected note on the Super Nintendo's tech specs: "Put simply, 16-bit refers to how much memory the system can process at one time." It is a hint at another structural conceit, one where each line consists of 16 syllables. Within these constraints, Sexton crafts a vivid portrait of Dinosaur Land and the wilder landscapes around his childhood home while also invoking archeological lodestone Ötzi the Iceman, the Dionysian poet Arion and Breughel's portrait of Icarus. The nine-year-old kid and the adult poet blur on the page, creating a compact but mind-expanding doubled portrait of the past.

With the release of Super Mario Maker 2 earlier this year, Nintendo fans have been expressing themselves by creating crashy, splashy and often silly Mario levels. Sexton's sustained and often devastating feat of personal cartography is even more impressive, a Super Mario odyssey like no other.