Chris Donlan on: Children's games

Or, how to play with Duplo.

Measured against most yardsticks, my 19-month-old baby doesn't really know very much. As I type this, for example, she is crouched in the kitchen, trying to start a conversation with the washing machine. Still, though - and trite as this sounds - every day, I learn a lot from her.

I appreciate that I would say this, but I think I've received the greatest education from watching her play. This is an area that, for some reason, I assumed that I had all figured out before she arrived in my life, and it's an area that it turns out I had a near perfect misunderstanding of. Everything I thought about how kids play turns out to be wrong, if my daughter is anything to go by. It's been amazing to get a truer sense of the way things really work.

My long-held belief, and I have no idea where I picked this up, was that play was much simpler for kids - and in a way a little more honest. Kids played with whatever they had to hand, and they needed no internal architecture to get them going. Rules were for adults, who had to be tricked, or at least bribed, into having fun. As were rituals, achievements, levelling up, the works. Kids, meanwhile, would have a laugh with anything they found lying around. John Ruskin used to play with keys when he was a kid - normal, everyday house keys. Simpler times. (Also worth noting: he grew up to be quite an odd man. Ruskin childhood rearing? Not an unqualified success.)

Anyway, this, um, theory of mine does not appear to be true. Based on the evidence I have gathered from a 19-month trip to Planet Baby (long may it continue) I would say that kids need rules when they play more than they need anything else. Not rules in the Draconian sense, of course, but they seem to need to know that play is going somewhere. From a very early age, my daughter has required some kind of structure to keep herself from getting bored. Building blocks were only fun once we had established basic aims, for example: I would construct things, and she would try to take them apart faster than I could build them. This keeps her busy for hours, but without that naturally-evolving competition, the blocks would be sat on the floor, doing little beyond waiting for me to step on them barefoot. (Stepping on Lego blocks, incidentally, even Duplo or off-brand Mega Bloks, is the true rite of passage modern adults have to undertake in order to emotionally attain the role once filled by their parents - who stepped on Lego blocks before them.)

It's been the same with video games, too. My daughter loves the handful that we've shown her, but she never loves them in quite the way that I will have anticipated. For example, have you played Toca Nature? If not, stop reading this crap and go and download it from the App Store immediately. Toca Nature is genuinely magical stuff: pure play, pure sandbox, pure invitation to mess around with mud and water and bits of bracken. That's if you're an adult. If you're a kid, it's a lot more complex.

The shorthand for Toca Nature - and it's brilliant shorthand - is From Dust without the end-game. Each time you load it up, you're presented with a balmy view over a stretch of 3D terrain. Maybe there will be a few trees. Maybe there will be a mountain, or a little river. This is your land, and you can do whatever you want to it. You can prod at it to create lakes or oceans. You can pull at it to create craggy Everests. You can use your finger as a hose for spraying numerous kinds of tree into the ground. Then you can spin the place around as much as you want, zoom in close, and do it all over again because - and this is my favourite thing about the game - there's no save button. No save! Every world is doomed to be lost the moment you close the app. The next time you open it up, you'll have to start all over again - which turns out to be absolutely ideal, of course.

For my daughter, though, this stuff is all dull. Instead, she's drawn into mechanics that I don't think I would even have noticed without her. Mechanics that impose a strange set of rules on Toca Nature's world. Each feature you place on the landscape brings with it a very specific kind of wildlife: deer may cluster around one kind of tree, for example, while rivers will soon feature beaver-type guys splashing about in the shallows. Beyond that, though, each landscape element also brings with it a resource - a berry, a nut or a mushroom, say - and these resources seem to be exclusively craved by a different creature. Bears don't like the food that comes with the trees that gives you bears, for example. They want something else. (Typical.)

In this way, Toca Nature seems to be teaching you about balance and moderation, and the hidden complexities of the wilderness. It's a lovely message, but one that is lost on my daughter, who simply wanted to learn the rules. Which fruit goes with which animal? Who eats the fish that you can send flopping around on land? Who eats the mushrooms? How does it all work? Open-ended play doesn't matter to her. Or rather, I suspect, she can't handle it just yet. What she craves are patterns to spot and rituals to test. She is starting to explore the world's capacity to create meaning.

The hilarious twist, of course, is that so am I. When I play Toca Nature, I tend to re-create the donut world from ToeJam & Earl, and each time I'm faced with the blank slate, I try to render that donut a little more accurately. If I dig deep, I realise that I still need an objective - even one I've imposed myself - in order to enjoy the fruits of a game that wrings its real joy from an absence of objectives.

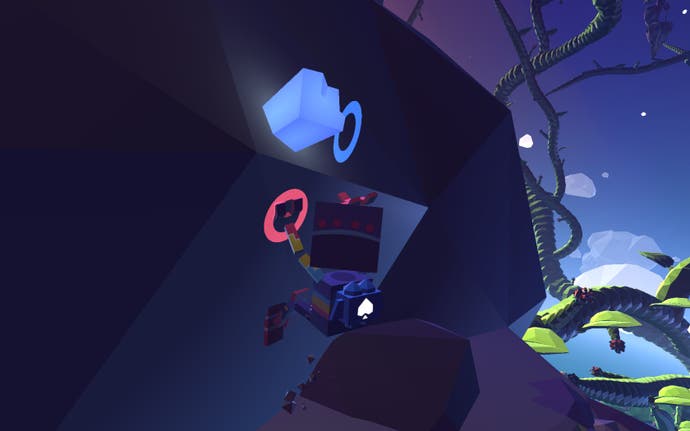

The same is true elsewhere. I've just headed back into Grow Home for a few more hours, and I've spent that time tracking down the last of the 100 crystals that are buried throughout the game's cheery, 3D landscape. I could spend an eternity telling you why I think Grow Home's collectables are the best since Crackdown - how they're fun to physically tug from the earth, how you can spin around on a leaf, listening out for the shimmering sound they make, how you can hunt for them at night, and how they're always stuck somewhere that's fun to get to. The most important detail, though, is that they give this beautiful game back to you after you've ostensibly finished it. They provide a strong enough goal for you to enjoy a game that imparts a real thrill simply as you scrabble over its glorious playground, sounding out every nook and cranny. Do I lose track of what I'm meant to be doing as I hunt for those crystals? All the time. Would I have returned to lose myself again if they weren't there? Probably not.

It seems fitting, really, that earlier this week I went to the British Museum to visit an academic working there who happens to be an expert in ancient board games. I'll hopefully be able to write the chat up properly for a feature over the next month or so, but I can at least mention here that he got very excited when telling me a theory of his revolving around the origins of language and games, and how they may both have evolved very quickly, out of an innate need for non-violent competition. "I'm me, you're you" may have been the foundational chunk of grammar from which all else springs, he explained, and games would have been there to reiterate that point: let's have a race, let's see who can flick these pebbles the furthest, let's see who can win this game. Maybe it all comes down to fizziness, to use the lovely term he employed: the brain sort of fizzes up with potential, and everything spews forth at once.

If he's right, watching my daughter muddle through her first games - probing for the rules, testing the boundaries - could be an insight of sorts into how games themselves began. And if he's not right, she still has the washing machine so it's not all bad.

Rich Stanton is away.