Retrospective: Command & Conquer - The Tiberian Saga

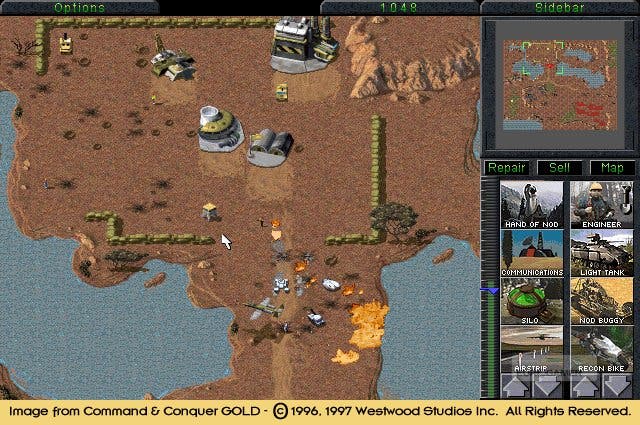

The land of Nod.

"I remember the day I picked up the newspaper after the War on Terror got underway, and saw the Global Defence Initiative labelled in the news," says Louis Castle, co-founder of Westwood Studios, the developer that created Command & Conquer. He laughs, leaning back on his chair in the EA LA meeting room where a handful of series vets have converged to look back over the landmark RTS series. "That was in 2003. So, it only took the real world eight years to get there."

As for Castle's team, they'd founded their own GDI back in 1995, but, despite the rousing name and the militaristic fetishes of the series - the colourful explosions, heroic tank rushes, and glinting piles of heavy armour - the story at the heart of Command & Conquer has always been uniquely ambiguous, rejecting easier answers about right and wrong, and using its opposing factions - the GDI and the Brotherhood of Nod - to explore conflicting perspectives on a single issue.

In the words of the current 'lore master' and campaign and story lead, Sam Bass: "It's about philosophical differences acted out through military action." So, with the Tiberian story arc coming to an end in the upcoming fourth instalment, previewed on Eurogamer tomorrow, it's time to take a trip back through the world of C&C: time for a refresher course on the story itself, and time to steal a quick glance at the ways the game has shaped RTS development in general.

Command & Conquer: Tiberian Dawn (1995)

"With Tiberian Dawn, one of the greatest innovations wasn't just that it was real time, but that we were going to dedicate a lot of time and energy to story," suggests Castle. "That's what separates the best RTSs: the complexity and the depth. Without the context of what you're doing, games can lack that connectivity. They can lack that epic nature."

By 1995, Westwood had already experimented with narrative elements in its last game, Dune II, the title that helped establish the RTS genre in the first place, and which broke up its action with tiny story vignettes. Tiberian Dawn may have used a modified version of Dune II's interface, but it would prove far more ambitious when it came to the plot. "With Tiberian Dawn, we had CD-ROMs, and we suddenly had all this data," laughs Castle. "What were we going to do with it? We decided we were going to do full-screen movies."

Enter full-motion video, the campy, charmingly primitive live-action film clips that broke up campaign missions and would quickly help define the series. The unintentional effect may have been humorous, but the story the FMVs helped relate was entirely serious, revolving around the geopolitical aftershocks of a meteor impact in the Tiber river in 1995, which introduces the Earth to an extra-terrestrial crystal, named Tiberium. "The hinge of the C&C universe is the sudden appearance of this strange mineral," says Castle. "It's a crystal that leeches all the great minerals and metals from the area around it, and brings it up into this crystal where it can be easily harvested. Once this starts appearing around the world, scientists realise they can break it down: it becomes an instant source of wealth and energy. Some scientists say it's a wonderful thing, and others are very concerned."

And how. With governments seeking to control the use of Tiberium, a charismatic underground leader named Kane soon emerges from the fringes, creating the cultish Brotherhood of Nod. They may sound like a consortium of those city trader types who like to dress up in romper suits and sleep in cots, but they're actually a kind of militarised pressure group. "Kane urges people everywhere to cultivate Tiberium themselves," continues Castle. "He wants to make the world an even playing field - he wants equality, and takes the side of the individual. Of course, he's labelled a terrorist leader by the western world for leading people against their governments."

In response to Kane, the authorities create the Global Defence Initiative. "Being in the west, we see these as the heroic force that's going to defend us against Kane's terrorists. But it's really important to remember that, since the beginning, Kane doesn't see himself as a terrorist, but as a liberator," says Castle. "And the GDI don't see themselves as a heavy-handed militaristic government, but as defender. That sets up a really great stage for epic conflict. Kane: heavily funded through shadow groups, but with unique tactics, very separate and broken down into groups. GDI: very organised, a very top-down structure, but slower."