Broadband Consoles - A Pipe Dream?

Article - everyone is expecting the next-generation of consoles to rely on the Internet, but have they really thought this through?

This week's MCV trade magazine includes an interview with David Gosen, Managing Director of Nintendo Europe, who takes time out of his busy schedule ramping up for the release of an unprecedented two major consoles in one year to discuss matters with the general public. The interview includes an amusing exchange between Gosen and rival SCEE number Chris Deering, who fishes for information on just where Nintendo are trying to pitch the consoles. Gosen's last word is that "yes Chris, consumers will be buying both."

Who's looking foolish?

Elsewhere in the interview, Gosen hammers home his thoughts on the way Sony and Microsoft are trying to market their products, and slams the multimedia device market, saying that Game Cube is a gaming device first and foremost, and that to do anything else in this market at the moment is suicidal. Gosen also slams his competitors' attempts to integrate gaming with mobile phones, saying that low-level ideas like the recent Pokemon Crystal mobile modem for serving statistics from Nintendo's servers can work, but that multiplayer gaming is not prepared for. He also makes an interesting point about broadband. Both Sony and Microsoft are using key market phraseology like "the centre of the home entertainment network" and "broadband-ready" to get people excited, and even Sega's new deal with Pace is to produce a "home gateway". The whole industry seems to be swooping on new standards such as DVD and the Internet, whilst ignoring what made it special in the first places; the games, or so he says.

Breaking eggs

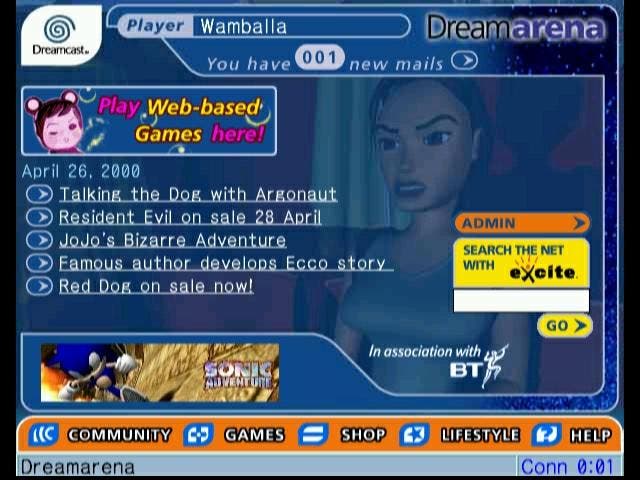

We agree with Gosen. When Dreamcast was first launched, the argument was that in time its Internet capability would win the market for it. This was an utter failure. Broadband didn't happen for the people Sega needed it to, and despite the Sony, Sega and Microsoft business plans to the contrary, it still hasn't. Uptake of ADSL in this country is limited to some 50,000 people so far, whereas in the USA, the system is plagued by problems with dodgy providers. Then there's the cost, in both territories. As for cable connections - for the most part, the companies that provide those have their own plans for the service with regard to gaming. Even Sony's plans to introduce broadband in Japan are meeting with problems. All of the companies hinging on this technology want to "pipe DVDs and television directly into your home" amongst other things, but they seem to have grossly underestimated the amount of bandwidth required for such tasks. Even the relatively simple process of streaming a movie using proprietary technology so that customers can pause a program mid-transmission and watch the rest of it saved to their hard-disks is going too far. DVDs running at full pelt usually use about 8Mbps, and many have said that Sony's fibre optic system in Japan, which is set to operate at around 3Mbps will be good only for low-movement scenes. Then there's the claim of a teletext style Internet interface amongst other things.

The Reality

Streaming a DVD at the speeds most DSL and cable customers are connected at; 512Kbps, is madness. It's also an incredible naïve assumption on everyone's part that a userbase of customers exists, that will be both willing to shell out for an expensive multi-Megabit Internet connection, and a top-of-the-range next-generation games console. Perhaps the most important fact that both companies have also forgotten is that even if they do manage to wholesale broadband Internet access capable of supporting this technology at a reasonable price to the average Joe, the average Joe will quickly become the average Joe, Josephine, Jill, Jack, John, Jake and all of their friends. This leads to propagation of one of the other big broadband buzzwords: contention. Contention, as we have explained before on these very pages, is the process whereby comparatively small Internet connections can be shared by users on the basis that not everyone uses all of their bandwidth all of the time. For instance, say your local exchange has a 2.5Mbps connection to BT. If BT sell five 512Kbps ADSL products to consumers on that exchange, each takes up 512Kbps, or 0.5Mbps and that means nobody is ever affecting anyone else's transfer speeds. Hence 1:1 contention. The idea though, is that since nobody uses all of their bandwidth all of the time, BT could actually install 125 ADSL products on that 2.5Mbps connection, because most of the time people would be able to use what they needed. 125 people sharing 2.5Mbps would be 50:1 contention, which is what most ADSL customers agree to be subjected to if needs be.

Flooring the concepts

Of course, for the most part this doesn't happen, mainly because uptake is slow, and also because as time passes by the local exchange is upgraded to help deal with capacity. The problem is, there are many associated costs along the way, for everyone involved, and once those exchanges are packed wall to wall with users, contention can manifest itself quite noticeably. Contention in itself works as a concept, because of people's habits for using the Internet. Some people use the Internet once in a while to check email, others use it all through the night, others early in the afternoon, some before school. Et cetera, it wouldn't be hard to believe that 50:1 contention could be unnoticeable under the right circumstances. However, when you take into account the broadband Internet model for console gaming, you hit a rather large obstacle: prime time. Consoles are generally played when people have the time, so theoretically any company that simply uses console Internet connections as a catalyst for linking up data online with data off will be fine. However, when little Joe arrives home from school and immediately hooks up with five of his best friends online, the fact that the Dad next door is downloading files from work and that the teenager two doors down is using Napster will have powerful effects on Joe's game. As for prime time movies and television shows beamed to the console via the wonder of broadband? Forget it; all it would take would be a couple of people on the same street doing similar things and it would fall apart.

Conclusions

The escape route? At the moment, using third party telecoms technology, there probably isn't one. The one feasible possibility is that companies allow for prime time requirements and download data locally in one go before it is requested, so in essence the various families living on Joe's street are watching data requested not three times simultaneously, but once on behalf of all of them. Is this possible? It's difficult to say. The process pretty much cuts out BT. BT won't like that. Will the recent tests Easynet have been conducting with an unbundled loop DSL connection in Battersea play an integral part? Once again, it's hard to predict. One thing is fairly clear though - at the moment each developer, be it Microsoft, Sony or Sega with their home gateway, are building products based on speculation and the promise that broadband will be ready. If you'll excuse the pun, the chances are the broadband console revolution will prove to be a pipe dream, leaving Nintendo in a very strong position, and as David Gosen points out, that's why the games are so damned important.