Crash Bandicoot is 3D gaming's underrated pioneer

Dogged.

Uplifting as it is to lose yourself within them, video game worlds are often most enthralling when you're aware of the tricks and contrivances that knit them together. Wolfenstein 3D's labyrinth is all the eerier when you know that it's a Pac-Man level masquerading as "true" polygonal 3D, its walls and columns projecting upward from sets of horizontal coordinates, like volcanic gas from a vent. And how about the Mode 7 landscapes of SNES role-playing games, glowing carpets spun and panned across to convey the impression of distant 3D geometry, or the bejewelled pop-up backdrops of the Sonic games? These realms would be nothing without their obvious, delightful artificiality - to wander through them is to revel both in the illusion itself and how it has been crafted.

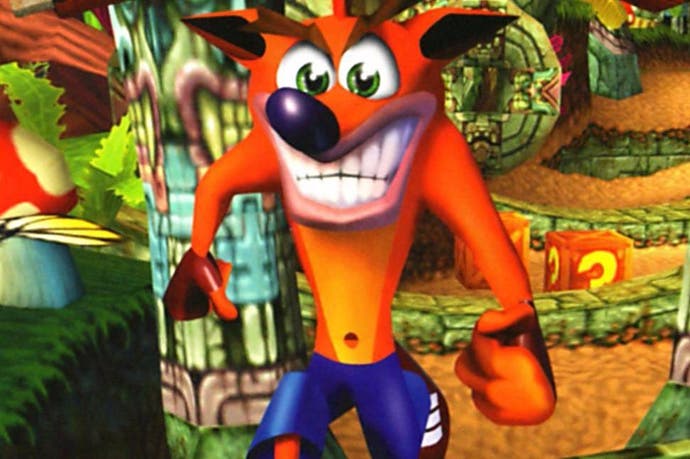

The same, I think, is true of Naughty Dog's reputation-making PS1 debut Crash Bandicoot, which amongst other things might be the least suspected nod to the work of cinematic pioneers Auguste and Louis Lumière in history. If you've seen anything filmed by the latter, it's probably the famous "L'Arrivée d'un Train en Gare de la Ciotat" from 1895 - a continuous shot of an approaching locomotive, taken from the front and slightly to one side in order to emphasise the sense of depth. According to urban legend, audiences at the time were so convinced by the illusion that they fled, shrieking, to the back of the theatre. Crash Bandicoot's intro sequence appears to riff on this, but whimsically transfers the shock and fear to Crash himself - it shows the character hurrying towards the screen only to skid to a halt, scream and duck as the title hurtles into view from "behind" the player. Whether intended or no, it's a fitting parallel for a game that - Bongo-bongo stereotypes and Jessica Rabbit clones notwithstanding - ranks among the first platformers to seriously grapple with the constraints and possibilities of 3D space.

When I first played Crash Bandicoot in 1996 its cartoon tropical island seemed a sprawling yet oddly inaccessible paradise, with acres of sun-blushed land stretching just out of reach. The rigidly on-rails camera felt like a cruel imposition, cheating me of the terrain I'd glimpse through the foliage. In fact, the island's bounty exists care of the camera's selective vision. The game's corridor environments were absolute behemoths by the standards of the age, encompassing millions of polygons - running them through the PlayStation 1's puny two megabytes of RAM was akin to persuading a gerbil to swallow the Empire State Building.

Naughty Dog's core team at the time - founders Andy Gavin and Jason Rubin plus programmer David Bagget, with Universal Studios vice-president (and later PS4 architect) Mark Cerny filling in as an informal "nth Dog" - achieved this partly by developing their own tools in tandem with the game, bypassing Sony's own restrictions in order to work as closely with the components as possible. Gavin went so far as to write his own programming language, while Bagget created bespoke compression software to reduce 128 megabyte levels to a relatively digestible 12. But it was also a question of creative erasure, or folding in cosmetic clutter in order to obscure a lack of substance. In order to keep the on-screen polygon count below 800, the maximum possible while running at a steady 30 frames a second, Naughty Dog was obliged to both script the camera's motion and delicately gut each level as it evolved, stripping out or hiding the geography to make room for props and enemies.

As detailed in a series of lengthy retrospectives on Gavin's blog, there are jungle ferns in Crash Bandicoot that are in fact just surface texture, their underlying polygons deleted to free up memory (but still visible through gaps in the texture). There are canyons that are choked with palms, jutting ruins and the like in order to save the game the trouble of rendering the scenery further afield. As with Wolfenstein 3D's ray-casting engine, everything on Crash's gleaming archipelago is to some degree just a product of perspective, coherent and solid from one angle only.

With the benefit of hindsight, what was once a gentle idyll seems downright unnerving: I'm reminded of the H.P. Lovecraft story "Through the gates of the silver key", in which a reclusive mystic is able to experience three-dimensional space from the outside, as a pitifully crude phantasm adrift in an unimaginable abyss. Strategies of this sort are hardly unusual today, but in the age of Jumping Flash and (ugh) Bubsy 3D the effects were rather miraculous, prompting accusations from other studios that Sony had granted Naughty Dog access to secret development resources. The same design economy underpins the game's fondness for crates. Their uses and abuses as explosive props, bounce pads, destructible platforms, checkpoints and treasure chests aside, these allowed the developer to populate stretches of terrain with interactive objects on the cheap - a cube is, after all, one of the simplest 3D polygonal objects to render.

Judged as a playset, Crash Bandicoot lacks the sheer imaginative and spatial reach of Super Mario 64, its greatest rival at launch. Where Miyamoto's creation is a cacophonous, burgeoning toybox, packed with one-off ideas and accordingly, a little rough around the edges, Crash is a lean, visually overpowering offering that combines the responsiveness of a 2D platformer with the ribald energy of a Loony Toons animation. Though a technological powerhouse, the game is designed to bridge eras rather than scuffing away all trace of what came before. But that doesn't make it any less entertaining, and if Mario 64 is more widely cited in platformer circles, Crash Bandicoot may have cast a longer shadow - both in helping to make PlayStation the world's best-selling console and in preparing the ground for Naughty Dog's later third-person shooters, which would apply broadly the same tunnel thinking to locales derived from 80s action cinema.

Crash and Nathan Drake seem a universe apart, but the former's enormous toothy grin is discernible beneath the latter's trademark smirk. For starters, Crash Bandicoot is one of the first 3D action games to solve what Rubin and Gavin termed the "Sonic's ass" problem - in less exciting language, the difficulty of making a character sympathetic when you spend the entire game staring at their backside. The studio tackled this in part by starting many levels off with Crash facing the camera, and taking every opportunity to spin him towards you - for example, by rotating a floating leaf as you travel along a stream. Leave Crash idle and he'll glance behind him suspiciously, in echo of Sonic's legendary foot-tapping animation. Naughty Dog also included side-on sections and a couple of more hair-raising levels featuring a massive rolling boulder, in which the player flees toward the screen. Perhaps most significant of all was Rubin's decision to eschew the simple skeletal animations used by many contemporaries, in favour of a more sophisticated vertex-based system that allowed for a wider (and goofier) array of gestures and expressions.

This style of game - bounteous because carefully directed, dealing in simple challenges backed up by effusive personality, a welter of technical tricks and a weakness for exotic caricature - would become Naughty Dog's stock in trade during the PS3 era, following the open world antics of Jak & Daxter. All of which is reason enough to sample the impending ground-up PS4 remaster, which includes series highlight Cortex Strikes Back (the court here acknowledges Eurogamer guide writer Chris Tapsell's fanatical love of Crash Team Racing). But it's also worth firing the original up again to investigate what you may have overlooked first time around, the elaborate fudgings and sleights of hand that make early 3D simulations of this sort so arrestingly weird.