Debugging the hero narrative in The Magic Circle

'Pure, unadulterated skullduggery.'

The Magic Circle, now available in Steam Early Access, delights in two things: messing with the typical hero narrative and playing inside baseball. Starting a new game feels a lot like dropping round a friend's house an hour before you said you would: the place is a mess, they're not especially happy to see you, but they're trying their hardest to be courteous all the same.

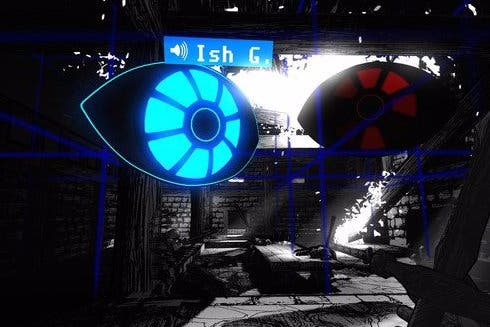

The same flustered 'oh crikey there you are' attitude seizes Ish and Maze, the game's fictional creative directors, as they try to ease you into the stereotypical fantasy game they've built for you to test. Their opening cutscene, still very much in the storyboard phase, grinds to a halt as they bicker over the necessity of a skip button. Moments later, you awake in a world of placeholder art and washed out colours. As you take up the sword to begin your quest, Ish and Maze resurface - as giant floating eyeballs - to have a full-blown argument over whether combat ought to be cut from the game entirely. So it is that, mere seconds after being armed for a fight, your only weapon is deleted from your hand with a sigh and an apology.

It's an arresting thing to experience as a player: ordinarily, we're used to worlds unfolding at our touch, purpose-built to serve us. As soon as you arrive in The Magic Circle, however, it becomes apparent they not only don't have a finished world, but its creators simply don't know what you do with you. Maze, focusing on the user experience, gamely tries to protect your right to agency within the world. The Molyneux-esque Ish, meanwhile, refuses to let anything - even the player - compromise his creative vision. Development on the game, you come to understand, has been in a state of deadlock for a long time now because nobody can agree on what they want to make. The traditional hero narrative is shattered; your presence, far from being the spark that brings the world to life, becomes an irrelevance instead.

The tension driving The Magic Circle offers an interesting peek at the stresses of game development. As the creative wonts of the developers run up against the necessity to entertain the player at all times and, potentially, at all costs, you get a real sense someone is speaking to you over and above the exaggerated characters supposedly in charge of the game. At points, it strays close to being heavy handed: as I watched Ish rant about the player as the "lonely mute who can't even lower his killing hand", I felt like a small child watching their parents argue. Something was wrong, I was powerless to help and yet somehow I felt like it was all my fault. It left me wondering how much the developers at Question used The Magic Circle to get something - or a whole host of somethings - off their collective chests.

Your onward journey through The Magic Circle calls up ghosts of the role you were once canonically destined to play. Violins, reminiscent of the screeching strings of Bioshock's soundtrack, are counted in with a soft whisper, only to die off a few seconds later when someone makes a mistake or notices this isn't the right part of the score. It soon becomes clear you're no longer a hero, you're a trespasser in a broken game. But how, then, are you supposed to make headway? It's simple. You break the game further.

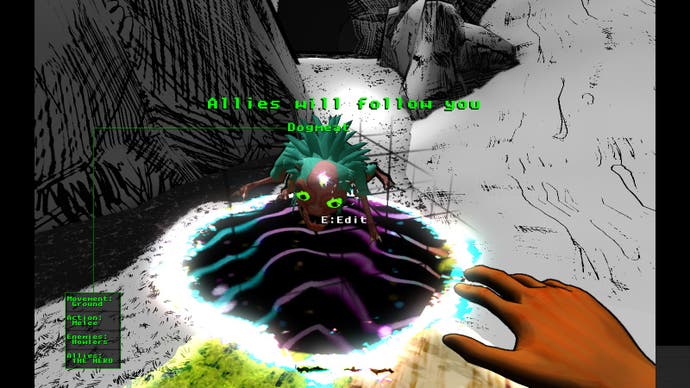

The Magic Circle's signature mechanic allows you to cast a circular trap that immobilises enemies, allowing you to edit their behaviours. Typing that sentence, I honestly only just realised that's probably why the game is called The Magic Circle and now I feel stupid. Anyway, you can pick apart the component elements of each creature - their loyalties, attack type, special ability and movement pattern - and recombine them to suit your needs. At one point, for example, I found myself stuck on one side of an impassable river of lava. Previously I got past this same puzzle by granting fire resistance to one of the game's larger creatures and riding it across like some kind of meat raft, only this time the river was too deep to allow the same tactic. After a frustrating few minutes, I remembered I could edit my creatures to give them an ability called 'teleport to other'. Throwing a newly modified cyber rat across the ravine, I jumped into the teleportation beam of the creature next to me and - hey presto - popped out on the other side, next to the rat.

Dipping in and out of the options menu for each creature is pretty intuitive, but it's the sheer variety on offer that makes it satisfying. Turning the game's systems against themselves, cheesing soon becomes your sword, meta-gaming your shield. Little by little, as you cobble fantastical new creatures together out of the failed dream of Ish and Maze, a new hero narrative is built up. You still have the chance to be the saviour of The Magic Circle, only you're no longer questing to defeat some canonical big bad. Instead, the world you inhabit becomes both your greatest enemy and your Princess In Another Castle at the same time. It's tremendously empowering as every advance you make in-game is down to pure, unadulterated skullduggery. Pitting The Magic Circle against itself, I felt a bit like Han Solo. The game cried 'you're not supposed to be able to do that here' and I, smirking, shot back 'I know.'