Definitive Years in Gaming History: 1991

Jaz Rignall on 1991's historical significance.

In May 1972, the Magnavox Odyssey was launched in the US. The brainchild of visionary electronics engineer Ralph Baer, this inaugural home video game console heralded the digital entertainment era and kick-started the games industry in one fell swoop.

During its first forty years, the games business has seen incredible growth, driven by amazing technological advances and bursts of genius that have helped it evolve from a specialised, geeky curiosity into a mass-market, pop-culture entertainment phenomenon. The rate of this growth hasn't always been consistent, however. While it's true that the industry has constantly moved forward on a wave of new ideas and innovations, there have also been brief periods of extremely concentrated activity, usually precipitated by specific market conditions, in which the industry has taken significant steps forward in a relatively short space of time.

It's these "burst" periods in gaming history that inspired me to write this article, examining how those momentous and hugely important spells have helped shape the games industry we experience today. So to that end, we kick off with 1991, a year that in many respects represents a temporal watershed between the early days of the games industry and the true beginnings of the modern era.

System Wars Go Global

The console war wasn't just limited to the bitter battle between the Mega Drive and SNES. The nascent handheld market had also become its own theatre of system war - an epic four-way battle royale between Nintendo, Sega, Atari and NEC.

So what was happening a score and one years ago? Well, gaming was in the midst of a revolution. The unassuming grey shoebox that was the NES, which had utterly dominated the Japanese and US markets for years, and Sega's bungalow-shaped Master System, by far the most popular video game system in Europe, were both in decline. The machine in the ascendancy was Sega's magnificent Mega Drive, whose lovely rounded corners, circular design cues and fabulous 16-bit technology made the previous generation of consoles look positively sad and bronchial by comparison. The Mega Drive was launched in Japan in late 1988, in the States the following year and finally in Europe in November 1990. By 1991, the 16-bit wonder was carving out a hefty worldwide market share for itself that was gaining momentum every month.

Meanwhile, Nintendo seemed to be resting on its laurels. This was somewhat understandable considering the company was still enjoying unprecedented dominant market share in the US and Japan, and wanted to continue to milk the last vestiges of the 8-bit market for all it was worth. But as it did, Sega spooled out an ever-increasing head start that seemed to be reaching the point of unassailability.

But finally, in late 1990, Nintendo fired its opening salvo in the 16-bit wars with the launch of the Super Nintendo Entertainment System in Japan. The second salvo followed nine months later, when the pointlessly redesigned console hit US shores in August 1991 in all its hideous angular grey and lilac glory. As usual, third-world gamer territory Europe had to wait even longer for it. But while Nintendo dithered, enterprising importers brought thousands of modded Japanese machines into the country and sold them to impatient gamers at a premium, creating a frenzy of anticipation ahead of its official 1992 European launch.

When it finally did arrive, the SNES was every bit the match for the Mega Drive, and eventually caught up with and overtook Sega's system to become the most popular 16-bit console in the world - but not before precipitating a fiercely competitive and unprecedented software development "arms race" between Sega and Nintendo. Both companies invested enormous amounts of money creating "killer app" flagship games for their systems to attract new customers, and in doing so created a golden age of software development that pushed the boundaries of gaming to new heights - much to the delight of players worldwide.

The console war wasn't just limited to the bitter battle between the Mega Drive and SNES. The nascent handheld market had also become its own theatre of system war - an epic four-way battle royale between Nintendo, Sega, Atari and NEC. Within the space of eighteen months, three technically advanced, but power-hungry and prohibitively expensive colour hand-held systems had been launched against Nintendo's much cheaper black and white Game Boy: Atari's Lynx, retrospectively looking like a PSP forerunner, Sega's Game Gear, essentially a mini-Master System, and NEC's PC Engine-on-the-go, the TurboExpress.

By 1991 each of these systems had some great games available for it, but none had hit critical mass for success. Instead, it was the Game Boy that was kicking ass and taking names thanks to its monstrous popularity - and vast software library. And as it did, Nintendo was learning a lesson that it would leverage time and time again on subsequent hardware generations: that success is not always contingent on having the most technically advanced system - instead price, innovation, usability and great games would do the job.

Over in the home computer market it was less of a battle, and more a war of attrition in which neither side looked likely to win. At the height of the 8-bit market in the mid 80's, Atari and Commodore had launched the ST and Amiga respectively. Clearly next generation machines, the general consensus within the industry was that these 16-bit micros would replace the dominant C64 and ZX Spectrum systems once consumers tired of them and wanted to upgrade.

But as the 90's rolled around, despite having five years to take up the slack in a home micro market that was increasingly running out of puff, neither new machine had achieved mass market success. It seemed that the majority of 8-bit computer users were moving en masse to the new and exciting gaming consoles. Perhaps helped by the fact that the parents of said users had finally realised what their kids already knew: the original marketing promise of home micros being used for homework, recipes, finances and all that other stuff was a load of crap, and the vast majority of them were simply used as games machines. Faced with buying an Amiga or ST at a huge premium versus buying a nice cheap gaming console to keep little Johnny happy, the latter was an infinitely more palatable and affordable option.

Another Day at the Arcades

Away from the home, the arcade industry continued on - although if truth be told, by 1991 that importance was rapidly beginning to diminish. Its "golden age" having already come and gone, arcades around the world were reporting steep declines in revenue - but even so, this year would witness a few last, triumphant hurrahs for coin-ops! The biggest of which was the release of the most significant and influential coin-op of the decade: Street Fighter 2.

I remember playing it for the first time at an arcade trade show in London (and having to be pretty much forcibly removed from it), and then rushing back to the office, raving like some kind of lunatic with hyperbolic Tourettes syndrome about how seriously amazing it was. I hadn't been so excited about an arcade game in years. So many buttons. So many combos. So many characters. Such sweeeet gameplay. My mind was well and truly boggled.

The impact Street Fighter II had on the fighting game scene - and indeed gaming in general - was simply extraordinary: it evolved fighting games a quantum leap in one single step and founded a legacy that continues unbounded to this day. It also became a game that every gaming magazine of the period had to mention on its cover in some way or another to ensure it sold copies. Kind of like the way women's magazines use the words "orgasm" and "sex."

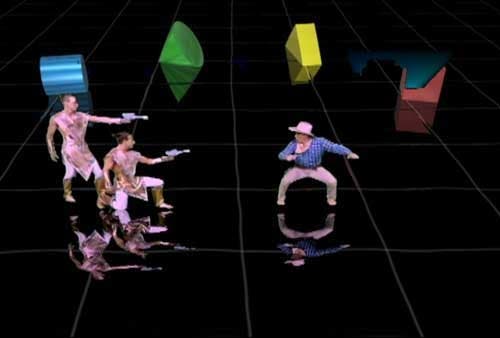

There were other, odder games. Time Traveler was a notable 1991 coin-op: a "holographic" arcade machine that used some brilliant visual trickery and a whole bunch of live action QT events to deliver an unprecedented gaming experience. Well, unprecedented in the fact that it looked really cool, with miniature live actors walking around the coin-op's play area like holo-projections from R2-D2. But unfortunately the gameplay totally sucked - it was just a crappy Dragon's Lair type game, but without the wit and charm. Still, throngs of people flocked to the arcades to see this wonderful new piece of gaming tech - and then swiftly grew bored of it after realising that it was in fact a phenomenally shiny, technologically polished "holographic" turd.

The other big game this year - and I mean big - was Sega's R-360. It's basically a bonkers version of G-Loc, a sequel to the Afterburner series that features a giant-sized, sit-in cabinet that can spin the player, tightly strapped into its seat, in pretty much every direction, including upside-down. It was quite the conversation piece, but, like Time Traveler, was really more of a novelty item than a truly great game.

Half the time it felt like it was just spinning you around just to mess with your head (and stomach), since it didn't seem to be accurately representing what the player's jet fighter was doing on the screen. But it was still a brilliant laugh, especially when your friend went on it after drinking too much and eating some greasy kebabs, and literally lost his lunch. Fortunately the entire machine was composed of rock hard plastic and metal tubing that could be easily and efficiently hosed down.

In retrospect, R-360 showcased the increasingly desperate lengths that the arcade industry had to go to keep declining crowds coming into arcades. Despite seeing some great successes in 1991 - both Street Fighter 2 and Time Traveler are on the Top Ten List of All-Time Grossing Arcade Machines - the reality was that faced with home gaming systems that were rapidly catching up with, and would soon equal, arcade technology, the sun was setting on the arcade industry. 1991 would be its final, golden year.

The SNES Shakes The States, Sonic Tries to Spoil the Party

In the US, the biggest month of the gaming year was August. That's when Nintendo finally rolled out its Super NES to the American audience, which came complete with quite probably the all-time greatest pack in game ever - Super Mario World.

What an awesome platformer that was. I reviewed the game later on that year for Mean Machines magazine, saying, "Super Mario World is the ultimate video game experience - the only bad news is that if you want to taste its excellence, you've got to go out and buy a Super NES." But despite there not being an official release of the machine in the UK, many people did just that, paying a premium price to enterprising importers who were shipping units in from Japan and converting them to run on British TVs via their SCART socket.

If you were one of the lucky ones to get an early SNES, there were a few launch games that were worth the money - the picks being F-Zero and Pilotwings, both of which showcased the SNES' Mode 7 brilliantly. UN Squadron, Gradius 3 and Super R-Type provided some decent quality shoot 'em up action if the other two games sold out (which they often did), and Sim City could be found at the bottom of the barrel if you were super-late to the Super Nintendo party.

By a strange coincidence - either that, or a well-calculated marketing ploy aimed squarely at heading off undecided gamers before they reached Super Nintendo Pass - a couple of months prior to the US SNES launch, Sega had come out swinging with its own answer to Mario: a certain blue hedgehog who went by the name of Sonic.

Created by AM8, which later became Sonic Team, Sonic the Hedgehog was a glorious, colourful, 16-bit defining character that burst onto the scene amidst huge hype. The game was absolutely terrific. While in retrospect it didn't quite have the finesse, attention to detail and craftsmanship of the very best Mario games, it nevertheless made up for its shortcomings with blisteringly fast graphics and some very fun gameplay.

R-360 was a brilliant laugh, especially when your friend went on it after drinking too much and eating some greasy kebabs, and literally lost his lunch. Fortunately the entire machine was composed of rock hard plastic and metal tubing that could be easily and efficiently hosed down.

Of course, both Mario and Sonic both became lightning rods for fanboy debate. Battle lines were drawn, and endless arguments raged in playgrounds up and down the country over which was the best. Once the dust finally settled, both characters would eventually kiss and make up and go on to star in several games together: an inconceivable idea in 1991, when Sega and Nintendo were locked in bitter war.

Another video game icon that hit big in 1991 was Link. The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past was released in Japan in November to huge critical acclaim. It wouldn't appear until the following year in the US and Europe, but since I played it in late '91, I'm including it here. Selling almost five million units, and seeing a second and third lease of life on Game Boy Advance and Virtual Console in '03 and '07 respectively, it's an absolute stone cold classic: one that deserves to be on every gamer's "play before you die" list.

A Link to the Past innovated in many areas: its outstanding landscape design and game structure, multi-level dungeons, weapon systems, solid storyline, superb puzzles and parallel world mechanic are all notable features that became franchise hallmarks - and influenced many other games in the action-RPG/adventure genre. Looking back at the Legend of Zelda now, its historical significance is clearly evident - its features and level of sophistication is far closer to what we'd expect from a game today than what had been seen in previous generations, essentially making it one of the earliest games of the modern era.

Motorbikes, Moogles and More

For motorcycle racing fans, 1991 was a vintage year. Road Rash made its debut on Mega Drive, kicking off a franchise that saw great early success before disappearing into obscurity for reasons best known to publisher Electronic Arts. I loved the series' combination of insane breakneck racing and violent vehicular combat, and would love to see a new version of the game.

But despite some apparent internal efforts to kick-start the franchise, unfortunately at this point it seems to have been left to rot in EA's front garden with its forks half-buried in the mud. The thing of real interest to me is that the Road Rash series still remains unchallenged as the most enjoyable and fun video gaming take on motorcycling some 21 years after its release, despite the advancements we've seen in virtually every genre of game. Is this because nobody can do any better? Or is there no market for it? Either way, methinks it would be perfect fodder for a Kickstarter project.

Another franchise was strongly established in 1991 with the release of Final Fantasy 4, renamed Final Fantasy 2 in the US to help avoid confusing American customers who'd only previously been exposed to the first NES Final Fantasy game. Regardless of the name - and indeed the fact that Nintendo removed chunks of the story to save space and eliminated seemingly innocuous religious references and graphics - this SNES RPG was an immense critical and commercial hit.

Of course, Europeans never got the chance to play the game, officially at least. Indeed, it wasn't until 1993 when a Final Fantasy game was finally released in Europe by Nintendo, and even then it was in the form of Mystic Quest Legend, a frankly dumbed-down version of the great RPG series. Utter bollocks, if truth be told. But that was the story of the '90s: Japanese console companies looked at their home market first, the American market second and the European market as an afterthought. Fortunately times have largely changed since then, but in 1991, the European release calendar was pitiful compared to the incredible volume of games released in Japan and the US.

But there was a silver lining to this red headed stepchild of a gaming territory cloud. The huge number of consoles being grey imported into the country, and the fact that some games sold better in Europe than they did in the US, finally caught the attention of the Japanese console manufacturers. At long last, they began to realise that the majority of European gamers had moved away from home micos, and that a whole new generation of gamers were emerging that wanted to play consoles. While it would still take years for the huge gap in territorial release dates to close, this was nevertheless a watershed: Europe was finally on the map as a legitimate gaming territory, and things would improve from this point onwards.

The Death Knell of European Hardware

While several European-built computers had been released to varying degrees of success during the 80's, by 1990, only Amiga had any kind of presence in the marketplace, and even that was beginning to fade. In a last ditch attempt to position the brand as a gaming concern to increasingly console-crazy consumers - a maneuver that was simultaneously tried by US-based Commodore - both companies released shiny, new consoles.

Well, they looked shiny and new, but really they weren't. The machines I'm talking about, in case you don't remember them and nobody would blame you if you didn't, are Amstrad's GX4000, and Commodore's C64GS. Both were cynical re-boxing exercises: the GX4000 was basically an 80's Amstrad CPC Plus computer with go-slightly-faster graphics stripes, and the C64GS was Commodore's almost decade-old C64 with a new case... and nothing else.

It wasn't until 1993 when a Final Fantasy game was finally released in Europe by Nintendo, and even then it was in the form of Mystic Quest Legend, a frankly dumbed-down version of the great RPG series. Utter bollocks.

The launch software range for each was pitifully poor - in most cases "new" releases were barely retouched versions of older games blown onto cartridges and sold at a higher price than their original cassette versions. And even more ridiculous, neither machine had the functionality and usefulness of their micro computer forebears. So why buy one when you could purchase a much, much cheaper original system that would work with the thousands of cassettes and disks released during the prior decade that were now available for pennies from friends or car boot sales? Why indeed? Fortunately, the public was not fooled.

Both consoles were dropped into retail with barely a ripple at the end of 1990 with the intention of capitalising on what would become a console-driven Christmas market...but neither made any headway at the peak buying season. As the year rolled over into 1991, both machines hit a sales wall and within weeks were being heavily discounted. Neither system would get an additional production run, and games in development were quickly canceled following abysmal retail reports.

Amstrad's machine, the lesser of the two evils, sold around 15,000 units - the vast majority of which were at almost giveaway prices. No sales figures for Commodore's effort seem to exist, which tells you how badly it sold, but rough estimates are in the region of 8,000. You can still find these machines on eBay, usually going for many times the price that they sold for, simply because they are such strange and rare gaming curios. But don't be tempted. Rhino turds are also rare, but you wouldn't necessarily want one.

With Commodore and Amstrad out of the race, the shift in the gaming market to Japanese-made consoles was complete. While the home micro market continued to soldier on, it was very much in the shadow of Sega and Nintendo. Of course, that would change somewhat with the rise of the PC, but 1991 was the year where the tipping point was finally reached between what had been a home micro-driven gaming market, and the shift to a new console-dominated business.

Of course, some might feel sad about that, but whatever your view, this change did precipitate some incredible advances in games and gaming. As we look back at this era from the present day, we can clearly see game genres, companies, franchises and even marketing techniques emerging during this time whose legacies continue to the present day. All that makes 1991 a year that almost perfectly divides the 40 year old industry into two, the watershed between the chaotic, pioneering experimental early days, and the more cyclical, predictable modern era.