Déraciné review - VR busywork elevated by the master of atmosphere

The return of the screw.

When I was a kid, libraries were often Victorian things. Alongside books, they sometimes had funny little exhibits: stuffed owls and old bones and things under bell jars, everything lining the lonely parqueted expanses of paneled corridors and generally in need of a dust. One library I knew in Thanet - the Isle of the Dead! - had a mechanical doll's house, one wall removed so the skeletal framework of rooms was exposed. Here was mum and dad in the parlour. Here was grandma in the bedroom and baby in her crib. There was a coin slot and a brass switch that triggered a whole bunch of unseen mechanical rumblings and then, when it wasn't broken, mum and dad would nod their heads over their papers, grandma would sit up in bed and the baby would kick its legs. Maybe there was a dog, too. There's almost always a dog involved.

The exciting thing was not what these automata did. It was the moment they started to do it - the sudden stirring of the silent and still and fixed and rigid into arthritic, juddering life. A few movements but no more. Mum and dad could nod their heads, but only nod them so far. They were trapped inside the smallest of moments. No wonder really that I have not thought of this family in years. But now Déraciné is here, and I thought about them constantly while playing.

Déraciné is filled with dioramas that come to life, only to perform the tiniest of actions: a bow, the opening of eyes, the lifting of a cap to reveal a bright key underneath. Pull on the PSVR helmet and find yourself two Move controllers, one for each hand. Enter the silent grounds of this old school where a handful of Victorian children live under the blank gaze of a master. This world is very physical, because, once you're wearing the headset, the place looms around you: ornithology prints, rucks in the carpet, stacks of books and dusty windows. Often, when wandering about, hopping, so as to avoid motion sickness, from one glowing spot to the next, and using face buttons to change directions, you will come upon one of the children, or a golden ghost of them suggesting a past moment, not long since elapsed. They will be very still, fixed and rigid, and then you will investigate and find the little glowing orb that triggers a memory. Maybe they will move a little: a lean, a gasp. They will speak a few words and, from one instance to the next, a story will emerge. Over the course of the four or five hours it takes to play through Déraciné, you will come to know all these children, their quirks, their individual fears and strengths. You will help to prod them through a narrative that's filled with unusual turns and surprising boundaries between what is possible and impossible, what is in and out of the fictional ruleset. But these children remain automata in the most atmospheric way: unconvincing 3D models, weird hair and teeth, dead eyes, something wrong in the weightless posing of the limbs. Déraciné did not cost too much money to make, perhaps. Perhaps that's it. But it has also minted a lovely kind of creepiness from its staginess and what I initially perceived as its shortcomings.

It's unsurprising really, given that this is the work of Hidetaka Miyazaki and a handful of other directors at From Software, in collaboration with Sony's Japan Studio. Manage your own expectations: if you're expecting the rigour of Souls' combat or the intricate, anfractuous spaces of its citadels and sub-basements, you're going to be disappointed. This is a point-and-click adventure game about schoolchildren. People die, but nobody picks up a sword or a combination walking cane and flail, and there are few moments where you realise - jeepers! - that seemingly distant points are actually connected by the ladder you just kicked down or the door you unlocked. Instead, there is a Soulsish sense of density to the lore around you. Every object you pick up comes with a note you can read to learn more about it, poetic and perhaps elliptical. Every relationship between characters seems to have promising gaps in it, mysterious absences that you have yet to fill in.

And then there's you. You don't play one of the children or even a master. Instead, you play a faerie - the ambiguous, perhaps dangerous kind from Susanna Clarke, rather than the twee sort who balance cheerily on the head of a hatpin - who haunts the school and possesses a limited agency to meddle with the things that go on there. The Move controllers are your hands, and your hands, here, seem to hint at things about you that you may have to keep in check. These hands are spectral and golden, but also slightly grasping, fingers naturally pulled inwards until they settle in a resting clutch. These hands have rings on their fingers that allow for powers that should not be spoiled, and alongside user interface duties like allowing you to store and access your inventory and read those notes about the objects you collect, they can conjure a magical fob watch that offers gentle guidance and allows you to leave each scene once its quiet business is concluded. A wonderful bit of VR theatre this: jobs all done? Well, produce the watch and then grasp it between both hands. And we're out.

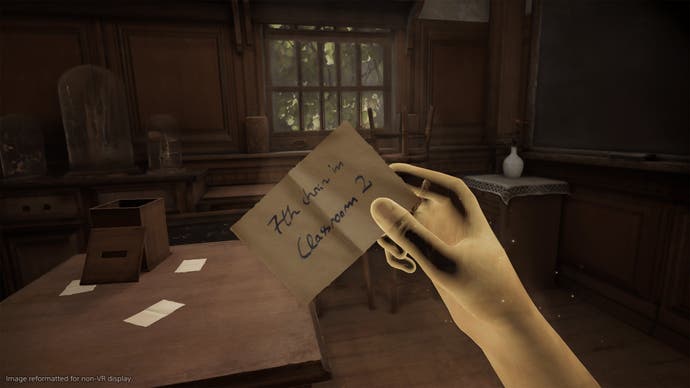

The game itself, as it plays across one moment to the next, is almost emphatically, almost audaciously unspecial. If you want to put someone off playing Déraciné, in fact, tell them what you get up to in it. Each chapter sees you solving some kind of conundrum for the children - grabbing herbs from each of them to put in a soup, say, or allowing them to access a part of the school that seems otherwise out of reach. There are some irritating instances of adventure game anti-logic in play here: a sleeping child in one section requires a very specific item to rouse them, and it's far less obvious than a handful of other things that would theoretically also do the trick. But there's also something quietly fascinating about the whole thing. The children know you're there, but they can't see you or interact with you directly. They seem to stare just past you while talking to you, and your actions are always greeted with great surprise. It really is a game about haunting people as much as helping them.

As the plot moves forwards - and backwards; in its timeline, at least, Déraciné has some of the Souls' games geographical complexities - you venture farther into the school house and the landscape around it. The presentation is always fairly basic, but VR works that VR magic and delivers a sense of scale befitting of a game in which you can be staring at a mountain range one moment and crouched in the snow inspecting the laces on a character's boots the next. Miyazaki's flair for Victorian creepiness helps elevate the rudimentary puzzles, too. These generally involve collecting items and moving them around the place, giving a flower to the right person or slotting the right key in the right lock. But when you step back and think about what you're doing, it's often arrestingly strange and sinister. At one point you have to stop one of the children from going outside at night and hurting themselves. A noble aim, perhaps, but the means at your disposal are rather troubling.

If Bloodborne puts you in mind of Dunsany at times, there's certainly a little of that here - and there are tantalising suggestions of crossovers, too. But there's also something of Henry James - a human darkness, glimpsed at a fusty distance through elegant veils. I finished Déraciné and didn't think of the slightly plodding adventure game I had just cludged my way through over the course of an afternoon. I thought of the place I had been to and the people I had met. I thought of those glowing hands, forever caught mid-grasp.