In Theory: 1080p30 vs 720p60 - could next-gen let us choose?

Digital Foundry on why trading pixels for frame-rate isn't quite as straightforward as it seems.

It's an intriguing thought. With so many next-gen console titles targeting 1080p at 30 frames per second, why not offer gamers the option of playing at 720p60 instead? After all, the ability to trade pixels for frames has long been part and parcel of the PC gaming experience - and both Xbox One and PlayStation 4 are based on x86 CPU cores and Radeon GCN graphics architecture.

The idea of resolution vs frame-rate is based on one simple idea: reducing GPU fill-rate - the amount of pixels drawn - frees up enough power to process frames faster, resulting in smoother gameplay, usually with more precise, lower-latency controls. As everyone knows, resolution reductions have been a key tool for developers to get Xbox One games running at similar levels to their PS4 equivalents, so clearly, what works on PC can work on console too.

However, the relationship between pixels and frames is not quite as simple as many people think. Pixel fill-rate is by no means the only limiting factor to frame-rate - bottlenecks occur at many different points in any given game engine, inside or outside the GPU. Perhaps most importantly, it's also important to stress that there is no linear relationship between pixel-count and frame-rate - resolution is just one element in the mix. Put simply, there are no guarantees that a game targeting 1080p30 could also run at 720p60. Indeed, even if the fill-rate issue is addressed by lowering resolution, there's a good chance that you'll hit another processing bottleneck before you reach the 60fps ideal.

A phenomenal amount of processing goes into every frame rendered by your console. For example, certain elements of the process - such as geometry calculations - are fixed regardless of resolution, while some frame-rate hitches may not be related to fill-rate at all, but perhaps due to vertex shading load or hold-ups within the GPU command processor. Moving outside of the graphics core, the situation becomes even less clear. It may well be the case that available CPU time is too limited to create the smoother frame-rate you're looking for.

"Battlefield 4 on next-gen console is a good example of how reducing resolution increases frame-rate - but we suspect that this was just the beginning of the optimisation effort."

Consider the comments made on hardware balance from one of the Secret Developers last year. The way games generally work is that the CPU simulates the scene, while the GPU renders it. Setting a 30fps target means that both CPU and GPU have 33ms to complete their tasks - something of a luxury compared to the 16ms for a 60fps game.

Dropping down from 1080p to 720p may well help to free up the graphics side of the equation, but there is absolutely no guarantee that the CPU will be done simulating the next frame in time. This creates a stall, meaning that in a worst-case scenario, instead of a smoother frame-rate all you have really achieved is less utilisation of the GPU and a less attractive, lower-res image. We actually saw this in action on the original Digital Foundry PC, which over time proved more adept at handling 1080p30 than it was at achieving a locked 720p60 - as seen most prominently when we gave it whirl on Spec Ops: The Line. We'd wager that a simple, unoptimised switch from 1080p30 to 720p60 on next-gen console would produce similar, variable results in many cases.

This is actually a real issue for the next-gen consoles, as the six CPU cores available to developers aren't exactly powerhouses. AMD's Jaguar architecture was designed with low-end laptops and tablets in mind - it's just that the ratio between power consumption and silicon die-space vs performance made it a good fit for the next-gen consoles. The typical CPU that finds its way into a gaming PC is much more capable in raw processing terms, so it's understandable why the trade between pixels vs frames works more frequently there - there's a lot of untapped resource CPU-side.

To illustrate, let's re-run a few shots from the performance gallery we featured in our Core i7 4770K review, where we compared the Haswell chip against its Ivy Bridge predecessor by running games set to ultra levels at 720p on a GeForce GTX 780, with performance-sapping anti-aliasing turned off.

"One reason that the PC fares so well in gaining frame-rate from dropping resolution comes from the surfeit of power found in a modern gaming CPU, eliminating a potential major bottleneck."

With the GPU side of the equation less likely to cause a potential bottleneck and with the game simulation completely unlocked, you get some idea of just how much latent CPU power there is on a well-specced PC, with Battlefield 3, Tomb Raider and BioShock Infinite able to run at frame-rates up to and over 200fps. In this sense, comparing the effect of a resolution reduction on PC with a potential result on console may not be a fair representation of the boost you'd actually get - CPU time is a much more precious commodity on PlayStation 4 and Xbox One.

Console game development is all about the expert marshalling of resources, getting more out of relatively modest hardware via the developer's complete control of the experience, so if user control of fill-rate isn't a particularly good idea, what if the tech staff are put in charge instead? Guerrilla Games' Killzone Shadow Fall is an excellent example of this.

In the single-player mode, the game runs at full 1080p with an unlocked frame-rate (though a 30fps cap has been introduced as an option in a recent patch), but it's a different story altogether with multiplayer. Here Guerrilla Games has opted for a 960x1080 framebuffer, in pursuit of a 60fps refresh. Across a range of clips, we see the game handing in a 50fps average on multiplayer. It makes a palpable difference, but it's probably not the sort of boost you might expect from halving fill-rate.

"Killzone Shadow Fall's multiplayer runs at 960x1080 with a high quality temporal upscale. Fill-rate is reduced, but we're still not at 60fps."

Now, there are some mitigating factors here. Shadow Fall uses a horizontal interlace, with every other column of pixels generated using a temporal upscale - in effect, information from previously rendered frames is used to plug the gaps. The fact that few have actually noticed that any upscale at all is in place speaks to its quality, and we can almost certainly assume that this effect is not cheap from a computational perspective. However, at the same time it also confirms that a massive reduction in fill-rate isn't a guaranteed dead cert for hitting 60fps. Indeed, Shadow Fall multiplayer has a noticeably variable frame-rate - even though the fill-rate gain and the temporal upscale are likely to give back and take away fixed amounts of GPU time. Whatever is stopping Killzone from reaching 60fps isn't down to pixel fill-rate, and based on what we learned from our trip to Amsterdam last year, we're pretty confident it's not the CPU in this case either.

At the end of the day, developers want gamers to have the very best experience, and setting out with a fixed vision for how the game plays makes optimisation, QA and a whole host of other behind-the-scenes development tasks a lot easier. Optimising for one fixed target just makes more sense, especially for multiplayer games, where everyone is on the same, level playing field. Indeed, if a radically transformative, game-improving mode could be implemented easily, we're fairly sure we would have seen it. Curiously, across the last generation, we have seen a small number of console games with performance tweakables, but in the majority of cases the standard settings have produced the best results.

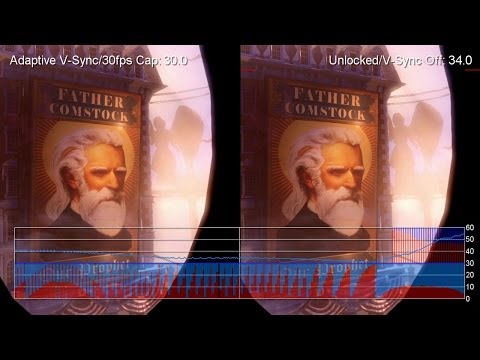

For example, the BioShock games have allowed the player to unlock frame-rate. This boosts controller response significantly, but introduces ever-present screen-tear that dominates the presentation, while frame-rates are so variable that the consistency lost in the experience is palpable. Elsewhere, we've seen v-sync selectables on the Saints Row games and Alan Wake's American Nightmare. In theory, it's a nice feature to include, but in practice getting v-sync right at sub-30fps is really difficult to pull off. On a general level, our thinking is that if 60fps is more important to you than it is to the developer, it's perhaps time to think of switching platform.

"Previous performance-related graphics options have been limited on console, with the standard presets usually offering the better experience."

The beauty of PC gaming is that you can configure both hardware and software to match your expectations for gaming performance. In many cases, this works out beautifully - as long as you have enough horsepower to blast your way past the limitations of the game engine. However, where this isn't the case, optimising the graphics set-up for your specific system can be an enormously frustrating experience, and we'd venture to suggest that it's well overdue a rethink.

Consider Crysis 3. The first two levels of the game put wildly different demands on your system; time spent optimising the experience via careful settings management in one area of one stage can amount to a total waste of time when you discover that GPU load can increase enormously just around the corner, or moving from one level to the next. Graphics options screens are also somewhat impenetrable in that we are given no actual indication of the GPU load any given selectable incurs and how much we lose or gain visually by adjusting the setting. Additionally, we never know where the bottlenecks may actually be in any given scene.

On top of that, there are often cases where - to the best of our knowledge - lacklustre PC optimisation simply can't be tweaked away. Take the PC versions of Assassin's Creed 4 or Call of Duty: Ghosts. We should reasonably assume that our current games system - a Core i7 overclocked to 4.3GHz working in concert with a Radeon R9 290X - should be able to run those games at a locked 1080p60. But it's not happening, despite a lot of time sunk into options tweakery.

"Introducing PC graphics settings to console isn't a great idea in our view. Indeed, we think that calibrating games for smooth PC gameplay needs a serious rethink."

Why? We don't know - we're given no information on what the bottlenecks are. What we could really use here instead of a bunch of context-free graphics options is a short series of calibration 'playrooms' based on the most CPU and GPU intensive areas of the game, where settings combinations can be tested in real time. An 'auto' calibration option that runs through these scenes would be really useful, along with frame-rate limiters - just like Killzone Shadow Fall's - for a more consistent experience. Similarly - in-game support for adaptive v-sync (mysteriously only available on Nvidia GPUs, and then only buried in the control panel) would also be welcome.

Bearing in mind our own preference for 60fps gaming, we understand the frustration some gamers may have about next-gen console titles operating at half the ideal frame-rate - but with the specs of the new hardware now a known quantity, it's understandable why developers are continuing down the 30fps route, and it's not all about the pixels. Equally, while the maths behind a prospective 720p60 vs 1080p30 selectable seem pretty clear cut, the reality is that dropping resolution only takes you so far in hitting the 60fps target.

In the PC space, a vast array of options are available for players to define the experience to their own expectations, but this is as much about investing significant sums on hardware as it is about careful settings management and even then, the results can disappoint. We're currently working on our "next-generation" Digital Foundry PC, and we're aiming to bring you our results next week. But one thing is clear from our preliminary testing: matching next-gen console quality is neither difficult nor particularly expensive. But in several key cases, achieving a truly transformative, significantly superior 1080p60 experience isn't as straightforward you may think it is...