In Theory: Nintendo's next-gen hardware - and the strategy behind it

Digital Foundry on the tech that best matches the Big N's revamped approach to console R&D.

Around 18 months ago, during an informal chat with an extremely well-placed individual in the hardware manufacturing business, an interesting nugget of information dropped into the conversation - Nintendo was already accepting pitches from third parties on the hardware make-up of its successor for Wii U. Two names were mentioned: AMD and Imagination Technologies, creators of the PowerVR mobile graphics tech. With the lack of backing sources, that little aside never made it to print, but as Nintendo strives to bounce back from the Wii U sales disappointment, eyes inevitably turn towards future platforms.

Is it too early to be talking about new Nintendo hardware? Perhaps - but the fact is that the firm itself has been very open about the general direction it is taking going forward, to the point where it has restructured its entire R&D around a new strategy, designed to address its issues in getting software to market, with fundamental implications for the technological make-up of its next-gen hardware. Handheld and traditional console are now overseen by a single, integrated department, run by Nintendo veteran, Genyo Takeda. The company is openly questioning the future of its business: whether to continue with both handheld and console, to combine them into a single product, or to perhaps expand the range still further. Whatever solution is chosen, integration is key.

"Previously, our handheld video game devices and home video game consoles had to be developed separately as the technological requirements of each system, whether it was battery-powered or connected to a power supply, differed greatly, leading to completely different architectures and, hence, divergent methods of software development," Satoru Iwata said during a corporate management Q+A back in March 2014.

"However, because of vast technological advances, it became possible to achieve a fair degree of architectural integration. We discussed this point, and we ultimately concluded that it was the right time to integrate the two teams. For example, currently it requires a huge amount of effort to port Wii software to Nintendo 3DS because not only their resolutions but also the methods of software development are entirely different. The same thing happens when we try to port Nintendo 3DS software to Wii U."

The difficulty of the process hasn't stopped Nintendo trying though, with some excellent results. For example, in our recent analysis of Super Smash Bros., we found two games that had as many commonalities as differences, while at the nuts and bolts level, titles like Mario Kart 7 on 3DS and its Wii U successor are fundamentally very similar games, based on a shared development ethos. Assuming Nintendo retains both a handheld and home console in future, we don't expect to see the firm releasing the exact same games on both systems; rather we expect to see titles similar to its existing efforts, tailored and refined for each audience - just with a common architectural underpinning that makes behind-the-scenes development that much faster.

"If the transition of software from platform to platform can be made simpler, this will help solve the problem of game shortages in the launch periods of new platforms," Iwata underlined.

It's an astute observation. Nintendo produces a unique style of game that Sony, Microsoft and the third parties can't - and usually don't even try to - match. N64 and GameCube demonstrated that Nintendo doesn't need to win the console war in order to be hugely profitable, it simply has to do what it does best - preferably with the killer software arriving at launch. The company is in a tough position at the moment, but it's not down to Nintendo losing its touch in terms of the quality of its games. Rather, it's been a question of logistics: with resources spread across two very different technological platforms, Nintendo's output has been held back, with launch periods for both Wii U and 3DS proving particularly troublesome. Neither was supported with a Super Mario 64-style game-changer, with the must-have software taking too long to arrive. The new integration strategy seeks to address this.

Historically Nintendo has been rather insular - behind the times, even - but Iwata and his team are now taking cues from competition in the wider world. In iOS and Android, Nintendo sees platforms that allow games to migrate across to many different types of gaming hardware.

"Currently, we can only provide two form factors because if we had three or four different architectures, we would face serious shortages of software on every platform," Iwata explained. "To cite a specific case, Apple is able to release smart devices with various form factors one after another because there is one way of programming adopted by all platforms. Apple has a common platform called iOS. Another example is Android. Though there are various models, Android does not face software shortages because there is one common way of programming on the Android platform that works with various models. The point is, Nintendo platforms should be like those two examples."

In short, Nintendo's new hardware should be adaptable, flexible and capable of running the same core code and basic assets across a range of hardware. While Android and iOS represent the kind of framework Nintendo aspires to, they do not offer the kind of granular 'to the metal' access to the hardware a console-maker requires. They are designed to work across multiple generations of different architectures, but the end result is often unfocused performance. Nintendo has a golden opportunity to partner with a single vendor that offers the same core technology and feature-set across a wide gamut of power levels, accommodating handheld, console or any other device the firm wants to develop.

The timing for Nintendo's more integrated next-gen strategy couldn't have been better. Recent trends in gaming technology are based very much on the kind scalability Nintendo will be interested in. Take Nvidia, for example. It developed the Maxwell tech found in Tegra X1 as a mobile architecture first and foremost, then scaled it up to top-of-the-line PC graphics cards. The potential of this kind of scalability for Nintendo is immense, though its published ideas on what form its architecture should take don't quite seem to make sense when the alternatives are so much more enticing.

"While we are only going to be able to start this with the next system, it will become important for us to accurately take advantage of what we have done with the Wii U architecture," Iwata said. "It of course does not mean that we are going to use exactly the same architecture as Wii U, but we are going to create a system that can absorb the Wii U architecture adequately. When this happens, home consoles and handheld devices will no longer be completely different, and they will become like brothers in a family of systems."

Here's where things get a little tricky. Creating a scalable platform isn't a vast undertaking in partnership with the right hardware vendor - but basing it on the Wii U is fundamentally a bad idea. The hardware make-up of Nintendo's last console is based on two key components - ancient PowerPC cores from IBM (the presence of which appears to have been dictated mostly by Wii back-compatability), along with DirectX 10-era graphics technology from AMD. While the Wii U was a power-efficient design, its PowerPC CPU architecture would be immensely difficult to scale down to mobile, while AMD left the kind of graphics tech utilised by the Wii U behind many, many years ago.

The many-core CPU approach, combined with AMD Radeon technology can be replicated - but only in the broadest terms. Iwata himself recognises the "vast technological improvements" made between the launch of 3DS and Wii U, but that incredible progress has pushed on to new levels since then, and it would be counter-productive to attempt to base new consoles on an existing, out-dated design.

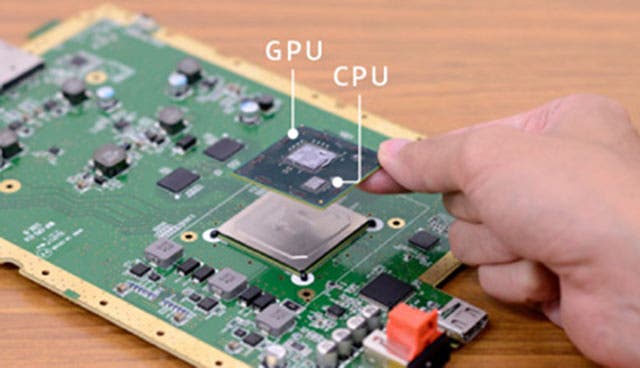

Wii U certainly has some interesting elements to its technical make-up - it's just that more modern technologies do the same job more efficiently and more cheaply. Nintendo incorporated both CPU and GPU into a multi-chip package, allowing for speedier interconnects and greater power efficiency. However, while an interesting solution, it lacks the elegance, integration and especially the cost benefits of the integrated SoC (system on chip), where all components sit on the same piece of silicon. Wii U also used out-dated production technologies - a 45nm process for its CPU, and 55nm for the GPU. Xbox One and PS4 both launched 12 months later with completely integrated processors at 28nm, the same kind of technology that would have been available to Nintendo if it had embraced a more modern design. For back-compat purposes, Nintendo may wish to hold onto the Wii U architecture, but on the flipside, the lack of commercial success for the latest Nintendo console means that there is less pressure for the firm to continue to support this feature.

Looking for other elements of the Wii U architecture that could potentially carry over to the next-gen machines is even more difficult, especially when the development tools are considered. In this area, Nintendo definitely needs to modernise. "The development environment for Wii U was horrible, clunky, outdated and very slow," a high-profile developer who worked on the system told us. "Nobody in their right mind would want to keep that moving forward. Even their asymmetrical setup of cores was strange and difficult to adapt to initially, with the CPUs being very weak and the GPU being quite powerful (for the time)."

What Nintendo is looking for in its next-gen hardware is a cheap, efficient architecture with in-built scalability, able to run comfortably in both handheld and console forms. We've mentioned Nvidia's enviable scalability, but there are plenty of other potential partners to choose from, kicking off with the two names mentioned in passing to us so long ago - Imagination Technologies and AMD. In the former, we see a UK company with some of the most advanced mobile GPU parts on the market - its eight-core PowerVR contribution to the iPad Air providing last-gen console-beating power in a tablet form factor. Its latest 6-series 'Rogue' architecture is a proven force on mobile, and based on the firm's whitepapers, the GPU should scale up to provide enough power to produce a generational leap beyond the Wii U.

Despite a lack of impact in the mobile market, AMD also has much to offer Nintendo in terms of scalable solutions. It already has Xbox One and PS4 design wins under its belt, and downscaled versions of the same technology are available for mobile form factors, via its fascinating, if woefully underutilised 'Mullins' processor. There's a huge power delta between its PS4 processor and the mobile-orientated Mullins, but Nintendo has already proven that it's capable of scaling games between handheld and console - and it has done so, albeit with difficulty, using two radically different architectures. The key here is easier integration and faster development.

Assuming that Nintendo's next hardware launch takes the form of a 3DS replacement, Nvidia is also in with a good shout at becoming the Mario maker's partner of choice. It's a proven SoC designer, capable of delivering stellar results on both mobile and larger form factors. There is some history there, though - 3DS was originally based on Nvidia Tegra hardware, prototype devkits where in circulation, but the deal went south for reasons unknown.

Timescale-wise, it's difficult to picture any new Nintendo hardware (be it console or handheld) arriving before 2016 - more likely 2017 - but what's important to keep in mind is that despite arriving midway through the console generation (as defined by Sony and Microsoft at least), the company is unlikely to utilise the absolute best technology available at that point. Nintendo views its hardware decisions in a very different way to almost every other games technology vendor. To use Genyo Takeda's parlance, a Nintendo machine is defined by a combination of technology and entertainment, not raw specs.

"Nintendo tries not to emphasise the raw technical specifications of our hardware," he explained. "We have focused on how we can use technology to amplify the value of our entertainment offerings, and in this sense, technology for us is something that stays in the background... It is not just the computational power of a computer that is important, but it is the way in which technology can connect with entertainment in ways that are easy for consumers to understand."

Historically, that has translated into weaker than expected processing hardware, married up with a state-of-the-art 'twist' - a 'magnifying factor' as Nintendo calls it, be it the ultra-low latency GamePad video streaming tech, the 3DS' auto-stereoscopic screen, or the Wii's innovative controller. The BOM (bill of materials, or raw cost) is also a key concern for Nintendo - an often-overlooked element of the Wii's success was the fact that it was significantly cheaper than the Xbox 360 and PS3 at launch. Nintendo's next-gen hardware doesn't need to be the absolute state of the art, but it will arrive when its competition will be cutting prices, and needs to be price-competitive out of the gate, whether it's challenging Xbox One and PS4, or the sheer ubiquity of smartphones and tablets on the handheld side. Hopefully the spectacular own-goal of the 3DS launch price-point will dissuade the firm from squeezing a price-premium from its early adopting core audience.

The question of just how powerful the hardware needs to be depends to a certain extent on Nintendo's approach to third-party support. Part of the problem with Wii U was the fact that it was attempting to do something new and different, while at the same time making a play for multi-platform developers - few of whom ended up putting a lot of effort into using the GamePad effectively, and who found it hard to translate Xbox 360 and PS3 titles across to a platform with a very different hardware balance. Meanwhile, Nintendo itself continues to produce unique, visually brilliant games irrespective of the spec. Third party software has never dominated Nintendo's bestseller charts - even during the Wii's period of market dominance - something Iwata himself acknowledges:

"Many people say that when a platform loses its momentum, it tends to receive little third-party support," he said. "But I think it is not a matter of the number of titles but the real problem lies in the availability of popular software that is selling explosively."

In short, it's a case of quality over quantity, with tacit acceptance that it will be Nintendo (and 'second party' partners) that once again provides the must-have titles that define the console experience. Getting the release schedule right is, as Nintendo has accepted, more a matter of logistics - integrating development to spread across its platforms, allowing for more titles from the existing teams. There's also the question of initial momentum. The Nintendo N64 hardware might have been delayed, but the wait was worthwhile - launching with Super Mario 64 and Pilotwings 64 (and Star Wars: Shadow of the Empire in Europe) saw Nintendo hit the ground running in a way that GameCube and Wii U couldn't achieve.

Nintendo's approach to game-making is straightforward enough - in theory, at least. It aims to create titles that, in its own words, "put smiles on people's faces", believing that it requires a combination of its unique approach to software with bespoke hardware designed to 'amplify' the experience. Both work in concert, meaning that Nintendo continues to shy away from developing games for other systems. It's impossible to predict what the amplifying factor will be for the firm's next hardware - perhaps the tighter integration between its devices will open up possibilities on its own - but what's clear is that Nintendo's new strategy can only mean good things for its talented designers, artists and engineers - and there's no shortage of potential hardware partners that can deliver the technology to match the integrated vision.