PlayStation Now's PS4 game performance analysed

The technology works - but where's the vision and content that makes it relevant?

There was a time when the idea of streaming games over the internet was the hottest, most disruptive technology in the business. Why buy a console or PC when you can stream gameplay over the internet? Why upgrade your hardware when servers across the internet can be upgraded instead, with no cost to the user? Why put up with extended loading and installation times when you could have near instant access to a massive library of games right at your fingertips? PlayStation Now does all of these things and it now supports PS4 games, so why isn't there more buzz surrounding it?

John Carmack has talked about early, broken VR implementations 'poisoning the well' for the more refined future technologies to come and there's a strong argument that OnLive did the same for streaming gameplay back in the day. At its absolute best, it showed the potential of the concept, but it's fair to say that the majority of the experience was blighted by terrible latency issues and dire image quality. Nvidia's GeForce Now has mostly addressed the technology challenges but hasn't attracted mainstream take-up, and our concern is that the same thing will happen with PlayStation Now - despite the service having much to commend it.

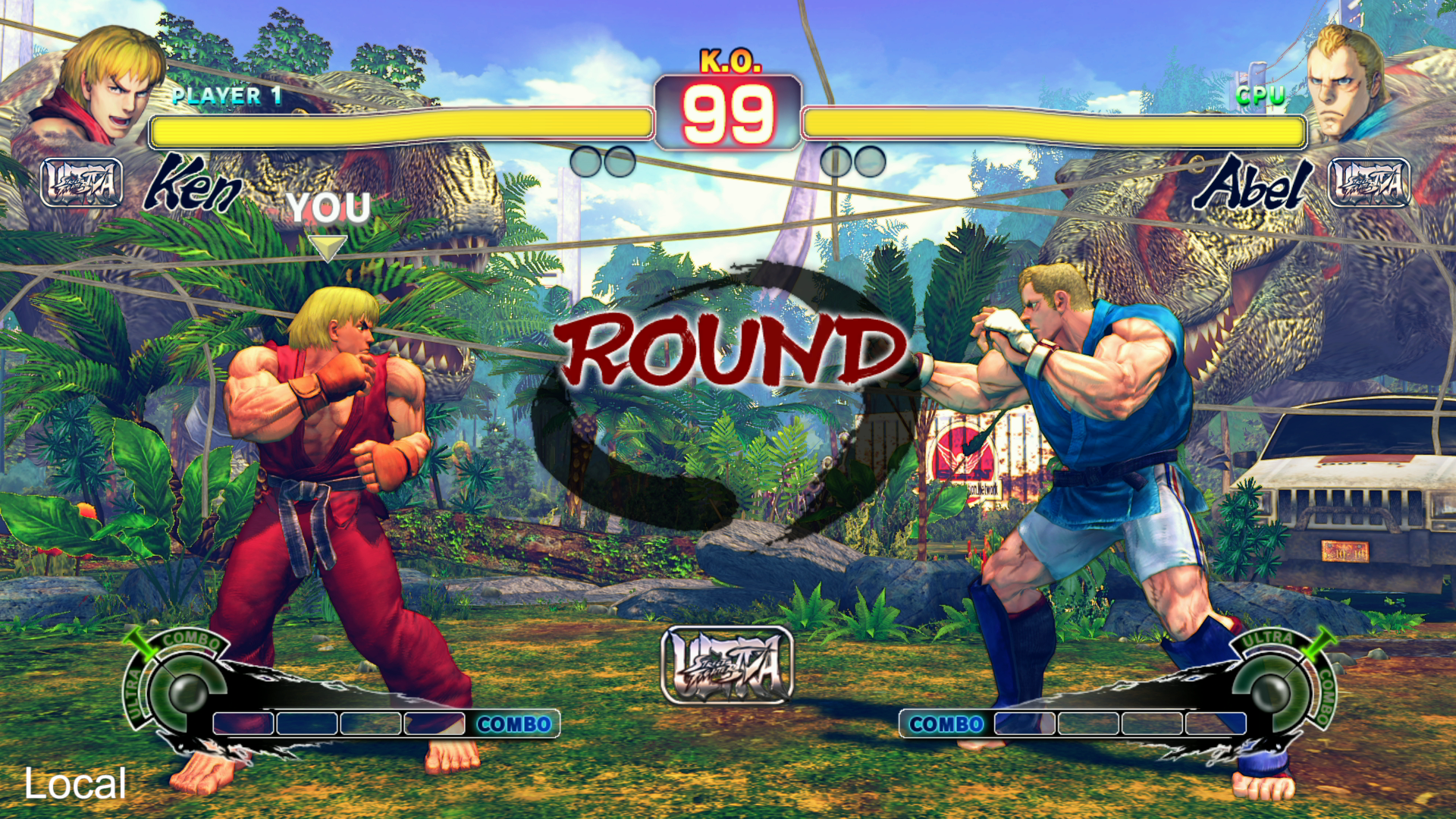

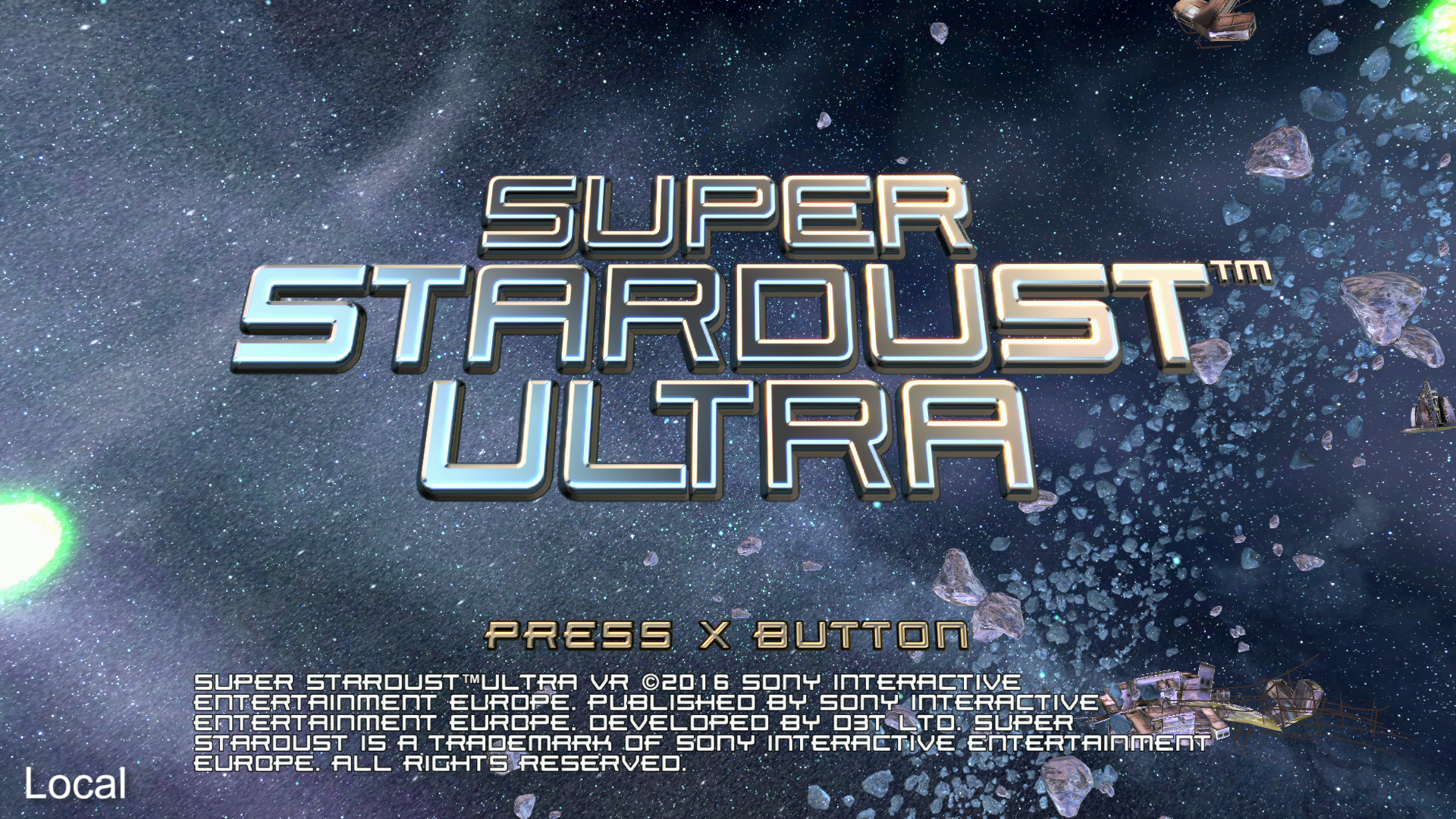

So here's the thing - historically, Digital Foundry hasn't been kind to streaming gameplay services, but it's also worth stressing that we have given credit where it's due. GeForce Now requires a hefty internet connection to operate at its best in its full 1080p60 glory, but it works. Just like PlayStation Now, there is additional lag but it's actually quite fascinating how much tolerance there is for extra lag in the gameplay experience when the raw metrics look poor. But the bottom line is that we spent a good amount of time last weekend playing titles like Ultra Street Fighter 4, Super Stardust Ultra, Resogun and Virtua Fighter 5 on PlayStation Now and found them to be enjoyable experiences. Crucially, even 30fps games like Killzone Shadowfall still hold up.

If you're interested in continued analysis of input lag in gaming, we highly recommend following Nigel Woodall on Twitter. He's crafted a remarkable capture-based device for measuring latency that requires no high-speed camera and he's supplied us with a version of his kit. We're going to be putting this device to a lot more use in the future, but for now, you can see some preliminary figures below, where we have benchmarked games running on PlayStation Now via both LAN and WiFi, then stacked them up against the same titles running locally on a standard PS4.

We used a standard 20mbps ADSL line for these figures and the general rule of thumb is that PlayStation Now adds four extra frames of latency to the core experience. That's 66ms or thereabouts where the image is compressed, transmitted over the internet, decompressed and displayed on your screen. The measurements are averages across several samples, so you can see that there is an extra layer of instability when gaming via WiFi that pushes the average higher. Games that run at 60 frames per second fare best - cumulative lag is lower, so it feels more responsive. End-to-end latency is effectively on par with a 30fps game, as you can see by comparing the Super Stardust Ultra PS Now figure to the local Killzone Shadowfall number.

Obviously it's not 100 per cent ideal, but in our tests with input lag on cloud systems, it's inconsistency that is most 'felt' during gameplay. PlayStation Now's extra four frames is relatively solid, and you simply adjust to the extra latency. If you don't have the original titles on hand as a reference point, pinpointing the extent of the lag is actually quite difficult.

However, even with this in mind, there is a kind of 'ceiling' where the effect is does become intrusive. Anything beyond the WiFi figures for Killzone and Heavy Rain and things start to feel somewhat Kinect-like. Another aspect worth factoring in is that our results do not include additional latency from your LCD display - game mode and a hard-wired LAN cable connection are recommended for the best experience.

In a sense, the latency figures proved surprising because both Tom Morgan and myself put some time into PlayStation Now and genuinely believed that the actual input latency would be lower than the final tallied figures we accrued from Nigel Woodall's equipment. For the games we played, it just worked. Image quality is more of an issue though. For its original purpose of streaming PlayStation 3 titles, it tends to hold up well - 720p video is transmitted from the servers and checking our router's admin panel, a good 12mbps of bandwidth is used to transmit the 60fps stream. PS3 titles are generally a little less busy visually, plus they tend to render at 720p or below, so it's a good match overall.

| Latency | Killzone Shadowfall (30fps lock) | Killzone Shadowfall (unlocked) | Ultra Street Fighter 4 | Super Stardust Ultra | Heavy Rain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local | 110ms | 108ms | 58ms | 38ms | 110ms |

| Ethernet | 174ms | 170ms | 126ms | 118ms | 172ms |

| WiFi | 185ms | 180ms | 128ms | 120ms | 188ms |

However, the specs don't alter when streaming PlayStation 4 games, meaning that the standard 1080p framebuffer gets a 720p downscale before encoding, then it's blown up to the display output set on the client. The result for PS4 titles is undoubtedly softer owing to the resolution downscale, but image quality is affected in other ways too - Killzone Shadowfall's soft volumetric lights cause clear issues for the encoder, causing some obvious macroblocking. Super Stardust Ultra's combination of constant fast motion and fine detail is even more of an issue - resulting in some ugly artefacting. It's still playable - but it just looks poor. The issue is exacerbated if you have the base PS4 connected to a 4K screen: an original 1080p image is downscaled, encoded, decoded, then upscaled to 1080p before the display itself upscales again to 4K. It's not pretty, but by and large, you accept a certain loss of fidelity with cloud systems.

So having established that PlayStation Now is essentially viable, what about the scale and scope of the service itself? PlayStation 4 support is limited to a fairly wide selection of indie titles plus a range of games that harken back to the console's early years. However, the PlayStation 3 side of things is far more robust with hundreds of titles available - and Sony first party in particular is highly represented (though there are some curious omissions - key titles like Gran Turismo and Resistance, for example). Take on the seven-day free trial and it's very satisfying to roll back the years and enjoy a deep slice of classic last-gen gameplay. There's plenty to dig into and immediately sample, but the telling lack of EA, Activision and Ubisoft offerings is clearly felt. Regardless, that level of instant access to so much gaming is undeniably compelling.

Dipping into the PlayStation 4 catalogue, the hit to the visual experience is palpable but the foundations are clearly there - and a world with no downloads, installation or patches takes us back to the original 'plug and play' console concept. There's genuine potential here for a more mainstream gaming service and for the core gamer, an upgraded PlayStation Now service could have much to offer. The issue with picture quality can be resolved with brute force, of course, as we've seen with GeForce Now, but the real question is the extent to which the cloud-based streaming technology can be integrated with the needs of the user.

What's clear is that the number one issue impacting take-up of the service is the pricing. By and large, Sony is offering access to a bunch of old games for £13 per month. It has created a serviceable 'Netflix for games' set-up then decided to charge a massive amount more money than any streaming service would dare to charge for its colossal library of film and TV content. A standard HD Netflix subscription costs £7.49 - about a third less than a PS Now sub - and let's not forget that the price-point is justified with its own range of premium, exclusive content. Sony has its own crown jewels of course, but automatically hobbles PlayStation Now by not offering users anything that isn't already several years old. The unfortunate reality is that games age faster than movies and TV, making the idea of charging £13 per month to access them difficult to swallow.

But the raw potential here is undeniable - it just needs more relevant, more impactful integration with the PlayStation user. However about a set number of hours bundled into a PlayStation Plus subscription? At the very least, a sampling mechanic for dedicated PS4 users would get more eyeballs on the catalogue. Secondly, how about adding cloud access to any PS4 title you own digitally?

The concept of fully playable access to your games wherever you are clearly has some value - and there is some evidence that Sony is planning for something along these lines. For example, it is indeed possible to port over save game progress from PlayStation Now to your local console - we were able to play Killzone Shadowfall via the cloud, then transfer our save to cloud storage and retrieve it locally on a standard PS4. It's a bit of a faff for now, but the foundations are there for Now to integrate with standard, local gaming.

Clearly, Sony has invested substantially into PlayStation Now and despite the sometimes wobbly image quality and extra lag, there's something here that works. Consistency in response - even if it's four frames behind local systems - seems to work in maintaining playability. Improved image quality for PS4 titles is a must, but even here, the system is still serviceable enough on most titles. But fundamentally, Sony has a history of experimenting with cutting-edge technologies then falling short in delivering quality content - PS Vita, PlayStation Move and even PSVR lack the support of Sony's top development teams. There's potential in Now, but it needs a genuinely exciting vision to make it truly deliver - a 'greatest hits' catalogue of old games at £13 per month isn't going to cut it.