Project xCloud: can Microsoft make a streaming platform that works?

The DF take on the new Xbox announcement.

It's no coincidence that less than one week after Google announced Project Stream, Microsoft has broken cover with more details on its own streaming platform, dubbed Project xCloud. The core idea behind both platforms is the same - and very familiar to longer term readers of this site. Rather than buy a console and play games on it, titles are hosted on the cloud instead. The user has a basic client device that beams input commands over the internet, with video and audio streamed back. The concept is simple - Netflix for games - but the application is somewhat more challenging. Prior attempts at getting this to work have fallen flat but Microsoft, Google - and other unannounced players - reckon that the time is right for the technology to work.

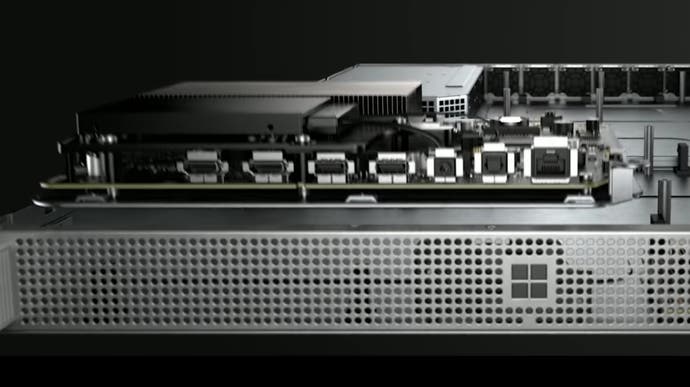

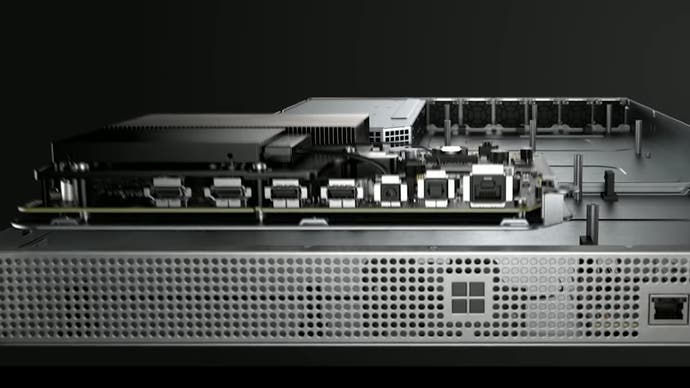

Microsoft's announcement trailer shows key first party Xbox franchises - Forza, Gears of War and Halo - running on tablets and smartphones. These are low-power devices incapable of running games of this complexity but what they do have in common is the inclusion of hardware-accelerated video decoding - and along with internet access, that's all that's needed for this concept to work. All the game code is hosted on servers within the datacentre, and the Microsoft reveal video tells us that the platform holder has built bespoke hardware for xCloud, based on a stripped down, rebuilt version of the Xbox One S console.

On the face of it, it might not sound as if there's too much new going on here. After all, PlayStation Now is built on the same principle of stock console hardware refactored into blade servers, hosted in datacentres. However, Microsoft is making specific claims in its video which could represent a fundamental improvement over the Sony offering in terms of image quality - and especially latency.

Based on our measurements comparing the same PS4 titles played locally and via the cloud via a standard ADSL broadband connection, PlayStation Now adds around 60ms of additional lag to the experience running on local hardware. And if your client device is hooked up via WiFi instead of Ethernet, you can add a further 10ms on top of that. It's playable, but it's not a great experience - and then we have the quality of the visuals to factor in as well. PS Now is an improvement over the platform that started it all - OnLive - but realistically, it's not good enough.

Fundamentally then, the challenges are clear - this 60-70ms lag has to be cut down to something far less noticeable. Breaking it down, that 60ms includes compressing the image, transmitting it over the internet, through your router to the client device and then decompressing and display the image on-screen. Ideally, to really pass for a local experience for most players, 15-30ms should be the target and it'll be fascinating to see just how close Microsoft gets.

So how can xCloud improve on existing streaming technology? Firstly, the implication seems to be that Microsoft has respun the Xbox One S silicon to facilitate lower latency access to the framebuffer. This allows Microsoft to grab the latest video data as quickly as possible before beaming it out over the internet. Systems like Nvidia GeForce Now and Blade's Shadow already do this. Microsoft's video also talks about new video encoding and decoding techniques, but fundamentally these will be based on standard formats - h.264 and HEVC being the most likely - in order to retain compatibility with phones, tablets and indeed smart TVs (hardware over which Microsoft has no control). There are latency savings to be made by scraping the framebuffer sooner, and video encoding speed is far faster than it was in the OnLive days. In theory at least, these two aspects of the process should be much faster than they were.

Beyond the servers themselves, Microsoft is banking on the sheer vastness of its infrastructure to reduce latency further. With its Azure set-up covering 54 regions and 140 countries, the Xbox cloud is indeed 'uniquely positioned', as Phil Spencer puts it. In terms of shaving off the milliseconds and ensuring a good experience for the majority of users, the amount of datacentres and where they are located is key - reducing the proximity between server and user is likely to be Microsoft's 'secret weapon' here. Only Amazon and Google can really compare in terms of the sheer amount of datacentre hardware it has out there.

After all of that, assuming that the latency issue is indeed resolved - or at the very least mitigated to a great extent - the next challenge is image quality. Flashback to the OnLive days and the fledgling service's 720p60 focus with a mere 5mbps of bandwidth proved to be a key aspect of its undoing as fast motion and colourful imagery would reduce the action to a mush of macroblocks. Again, technology has progressed here on several fronts. First of all, compression quality has improved and the arrival of HEVC encoding (and decoding on pretty much every modern phone and tablet) offers anything up to a 100 per cent improvement in efficiency compared to h.264. It'll be interesting to see the route Microsoft chooses to take here on mobile devices, where the smaller screens make sub-1080p encoding resolutions more viable.

In the home, the general increase in available bandwidth since the OnLive days obviously helps a great deal too - to the point where Google's initial Project Stream demo requires 25mbps of bandwidth (similar to Nvidia's GeForce Now). However, Microsoft is aiming for a broader audience and says that the current xCloud demo operates at 10mbps, opening the door to more home users and both 4G and 5G mobile devices.

Assuming that the technological hurdles are overcome, it's all about what the platform itself offers and when it will be delivered. Microsoft has surprised me here in showing a fully working prototype system so soon after its announcement at E3. Rather than wait to debut its streaming system alongside the next-gen Xbox, Microsoft is aiming to deliver a fully established platform to developers and publishers - the same platform they've been creating games on for the last five years and one that even has full compatibility with hundreds of Xbox 360 games. And in turn, Microsoft's GamePass subscription service takes on a new dimension, offering instant access to a wealth of titles, without the fuss of multi-gig patches or annoying system software updates.

It also gives Microsoft a big advantage over its competitors at Google - content. Our understanding is that the Google system, codenamed Yeti, is a new platform built from the ground up, based on Linux and using the Vulkan graphics API. As a new platform, it's designed with the future in mind, with specs that are comparable to those projected for the next-gen consoles - but that also means that it's going to take time to build a library of games. By focusing on its existing hardware, Microsoft can seamlessly add streaming to the Xbox One platform - and in theory all titles could be playable on mobile devices day and date with the standard console launches.

Drawbacks? The video demonstrates the issues found in transplanting across games designed for what is - relatively speaking - a very complex input interface. An Xbox One controller with a clamp for your mobile device looks unwieldy, while the idea of bespoke touchscreen interfaces may work well for, say, an RPG, but won't cut the mustard for a fast-paced shooter. There is also the question of accessibility: Microsoft talks about Android phone compatibility in its video, likely because Apple won't allow another game platform to be hosted within its ecosystem (Steam Link remains unavailable on iOS).

The irony is that poor WiFi reception apart, the Switch is actually the perfect platform for hosting streamed Xbox games, combining portability with a decent input system. And in turn, that makes me return to another of Phil Spencer's E3 pronouncements - the plans for more than one next-gen Xbox system. This is just the beginning of Microsoft's streaming enterprise and I still fully expect next-gen titles to run on the system too when the time comes. But even before that, a bespoke mobile device with a Switch-like form factor built for streaming Xbox titles suddenly makes a lot of sense...