Call of Duty: Warzone declassified - the Digital Foundry tech deep dive

Infinity Ward reveals how it delivered 150 players on the biggest COD map ever at 60fps.

When we look back at a console generation for its greatest hits, it's invariably the first-party titles that dominate - but sometimes multi-platform technologies emerge that are truly exceptional, and the fact they need to accommodate four very different consoles plus myriad PC hardware configurations only adds to the scale of the achievement. Today, Season Four of Call of Duty: Modern Warfare arrives - and I'd suggest that the IW8 engine from Infinity Ward is one of the most impressive accomplishments of the generation.

Modern Warfare 2019 is the most complete COD package of the modern era. We've reported before on the key technologies that make it stand apart - an engine that renders in both visible, invisible and thermal spectrums (!) while also supporting volumetrics on every light source. IW8 shifts to a physically-based materials system, bringing COD into line with the most advanced engines in the business, and offering a beautiful level of realism from every authored asset in the game. Geometry is also massively improved, delivering an unprecedented level of detail to the Call of Duty franchise. All of this is achieved in a title targeting 60 frames per second.

IW8 also revamps the background streaming system, using a hybrid tile-based approach, opening the door to bigger, more detailed worlds. It's the reason why the campaign is more detailed, but it's also how Infinity Ward delivered the vast Ground War mode of the launch code - but battle royale takes this to another level, as I discovered when visiting Infinity Ward's tech hub in Poland at the end of February. I spent the day with Principal Rendering Engineer Michal Drobot, who is also the studio head of the Polish arm of the developer.

To begin with, it's true to say that Treyarch presented the first COD battle royale, using its own engine to deliver 2018's Blackout - but aside from some initial tech sharing based on the Black Ops dev's super terrain technology, Warzone was built independently. And what's fascinating about it is that a whole slew of new techniques were deployed to make battle royale possible - but all of these systems integrate with the other game modes too. The optimisations that make Warzone possible feed back into every other mode, improving performance.

Infinity War's objectives for Warzone were ambitious. The aim was to create a battle royale map that had the same level of fidelity and detail as the core multiplayer maps - and that's precisely what's been delivered. The multiplayer maps are the battle royale map. When the locations are authored, they are done so within the overall canvas of the Warzone map. This makes Warzone the largest map in the history of the Call of Duty franchise. Its basic structure is derived from satellite data - it's shrunk down to a certain extent but its geography mirrors the landmarks of a real city, with the downtown section alone comprising of six districts. A Ground War map takes around four to five months to successfully execute and there are seven of them contained within the single Warzone map, along with other major multiplayer maps - and that's before we factor in the connective areas of the map between these major blocks.

There's also continuity too. If you've been playing Modern Warfare across its seasons, you'll note that there's been a consistent narrative emerging that spans across game modes - so the upshot of this is is that not only are the multiplayer maps contained within Warzone, if the content changes as we move between seasons, that should be reflected across all modes. I also like the way that the Infinity Ward taps into their own heritage - Modern Warfare 2019 is a reboot, but there are nods to the old continuity. The TV studio in Warzone is a remake of the map found in Call of Duty 4, the original Modern Warfare. The gulag essentially the same structure we saw in Modern Warfare 2 and its recent remaster.

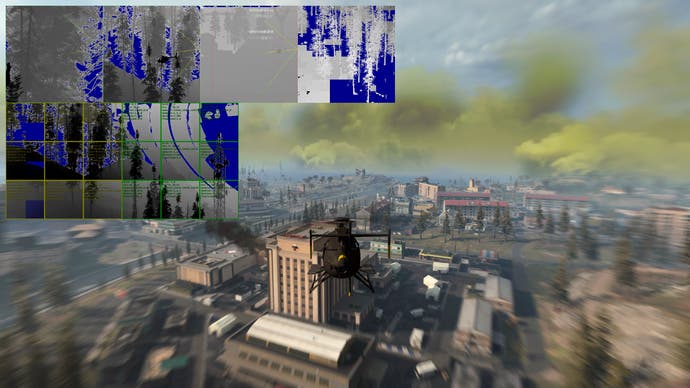

Making all of this possible is the process of technology evolution within the IW8 engine. The hybrid tile streaming system that Modern Warfare 2019 shipped with has radically evolved. The fundamental idea is still the same: tiles or chunks are loaded into RAM based on an algorithm that determines the priority of data most likely to be needed as you look around the terrain and move through it. In the video above, you'll see the debug tools Infinity Ward uses to visualise the streaming system. Environmental 'chunks' can be sub-divided into four smaller chunks, and they're three levels deep. Streaming begins with what Infinity Ward calls transients, the foundations if you like, and on top of that is loose loading for meshes and textures.

Accommodating Ground War and Warzone's needs for extreme visibility across big maps, the refined IW8 engine has a fascinating level of detail systems. LOD0 is, as you might expect, the full detail model authored by Infinity Ward's artists. Further out, you get LOD1 - meshes and textures are distilled down and simplified into a single block. I got the chance to see the various LODs at close-range in a way that they were never meant to be seen, and it's interesting how well LOD1 holds up. I also saw a LOD1 chunk in situ within the game, and again, I was hard-pressed to tell the difference at the range it was rendered at (which was closer to the player than I expected). The final level of detail is LOD2, which takes four LOD1 chunks and simplifies them again, collapsing them into a single chunk.

Also key to level of detail are the use of imposters. Elements like trees can be pretty difficult and costly to render and at range, you're potentially paying a heavy cost for rendering something that's really small and may only occupy a few pixels on-screen. Imposters are used fairly commonly now (Fortnite is a good example) and the idea is straightforward enough. When an object is far enough from the viewer, there's no need to render a 3D model at all. You can use a 2D billboard - a flat texture, a single triangle - instead. Typically, each object has 36 billboard variations, designed to represent the 3D model viewed from various angles. Trees are the obvious example for the use of imposters but other elements get the billboard treatment too - vehicles, for example.

Streaming, memory management and accurately predicting what data is going to be needed and when is essential in making the larger scale Call of Duty work. It satisfies the design objectives in allowing artists to equal core multiplayer map quality and to run the game at 60 frames per second. The entire approach also allows Call of Duty to do things in battle royale that is competitors are struggling to match. For example, Warfare has internal access to pretty much every building there is and not only that, these interiors were properly modelled too, in a world where some titles use procedural generation to fill empty spaces with what looks like random clutter.

The latest Call of Duty engine does use procedural generation, however, mostly for incidental detail on the terrain: foliage, rocks and other random items. In fact, pretty much anything that doesn't impact collision detection is procedurally generated and the nature of what you get depends on the surrounding biome. This is procedural generation and not random generation, so the same seed variable is used for all players on all systems. In practise what this means is that the nature of the environment is identical to all players on all systems, something we verified by capturing crossplay Warzone on PS4 Pro and Xbox One X, while spectating the same player. Procedural generation adds to processing time of course, but the bigger win comes from a reduction in the storage footprint: Infinity Ward reckons it saves around five to six gigabytes of data.

More instrumental to actual performance is the new shadow map caching system, which required a fundamental revamp, as shadow rendering is essentially incompatible with the chunk-based streaming system. Imagine the sun quite low in the sky, with light hitting a tall skyscraper. In theory, its shadow could cast across the entire map, way beyond the single chunk the building resides in. At the basic level, the new caching system brings in the most efficient shadow map based on the view frustum, with a level of detail system used.

Wavelet compression technology, used in video compression, is used to reduce the footprint of shadowmaps versus standard birmaps. In terms of what is actually streamed in and when, the new set-up is an efficient caching system with building blocks similar to those found in actual an actual physical CPU. Infinity Ward talks about building is own prefetcher and predictor - the same language used by Intel and AMD processor architects.

It's all very clever but what fundamental difference does it make? Going back to the launch of Modern Warfare 2019, the closest thing we had to battle royale was Ground War, and there the tech team discovered that for pretty much the first time in COD history, they were CPU-limited. The new shadow caching system wasn't devised solely for use by Warzone, it wasn't a battle royale-specific piece of tech, it's an optimisation in the truest sense of the word - taking something that already exists and making it better, meaning that it's rolled out to all areas of Modern Warfare 2019. CPU-bound limitations in Ground War are therefore eliminated. A revamped shadow caching system is also in place for other shadows - those which are not cast by the sun. Especially for indoor locations illuminated with spot light, this system also caches in shadows. There are 64 slots of prefiltered shadow maps here with eight shadow updates per frame. Again, similar to the main system, it's not something that runs on a per frame basis - and it doesn't really need to.

Back in the day, Call of Duty shipped with two physical executables - one for the campaign, the other for multiplayer with both presumably optimised accordingly. A core change in philosophy has seen this approach binned in favour of a unified codebase that brings together all technology into a single package - but ongoing optimisation means that all parts of the game cumulatively benefit. The Pine level, for example, launched on PlayStation 4 Pro not quite hitting its performance target. It still maintained 60 frames per second, but it had to lean into the dynamic resolution scaler to reduce pixel count and ensure full frame-rate.

Foliage rendering has significantly improved since launch, so there's an improvement in resolution. In fact although you won't feel it in terms of frame-rate in this specific case, render times generally are improved by 10 to 20 per cent. Similarly, optimisation across the board with each new title update has also seen progressive improvements to overall performance. On a content level, Infinity Ward has targeted the multiplayer maps as a priority for improved performance because that's the area of the game most players are accessing but the knock-on effect is that systems in campaign run faster too.

Speaking to Infinity Ward, I made a startling discovery. When you stand back and look at the four console platforms, there is a lot of commonality between them. All of them use the same core AMD Jaguar CPU technology and they all feature AMD's GCN graphics architecture. While this may be more straightforward than the Xbox 360/PlayStation 3 set-up of the last generation, the tech team estimate that around 30 per cent of their time is spent addressing multi-platform development issues. Interestingly, Infinity Ward ranks PS4 Pro as the most challenging of the four current-gen consoles that Call of Duty is available for.

Put simply, the expectation from the user base is for 4K video output, but Sony only gifts developers an extra 512MB of RAM to play with. Meanwhile, the boost on Xbox One X is four gigabytes in total - eight times as much. This opens the door to higher resolution, but also gives the streaming system much more room to stretch its legs. Theoretically, this should result in less pop-in and less aggressive LODs over longer distances - but head-to-head video doesn't provide much in the way of a noticeable advantage.

With consoles targeting 60 frames per second, Call of Duty has to cram the rendering for each frame into around 16ms, and this broken up into two distinct phases. First of all, the basics of the scene are calculated and lit - a process that takes around seven milliseconds. The next seven milliseconds is spent on basically everything else: volumetrics and post-processing, for example. Around 1.5 to 2.5 milliseconds is spent on temporal upsampling - integrating visual data from prior frames into the current one. The more detail rich a scene is, the heavier the cost in rendering terms. Asynchronous compute is used on all systems, including PC. It's more heavily optimised on consoles though, providing performance uplifts of around 20 to 30 per cent in the expensive scenes. Systems like volumetrics and particles can run asynchronously.

All of this technology comes together to make Warzone possible - and even factoring out IW8's application in campaign and core multiplayer, its deployment for battle royale alone sees a radical improvement in technology, visual fidelity and performance over other genre entries. Compare and contrast with the fortunes of PUBG that launched late in 2017 and it's fascinating to see how colossal the improvement is in every regard in less than 2.5 years. Back in May 2019, I first visited Infinity Ward to get a breakdown on the technological leap delivered by IW8, and it was clear that this engine was designed to straddle the generations and to allow Infinity Ward and other COD studios to transition more seamlessly to PS5 and Xbox Series X. What we didn't know was what hardware the developers would have access to.

While Infinity Ward itself wasn't sharing specifics, it's easy to see how the existing systems could transition across to next generation hardware. Extra graphics power means denser visuals, obviously, but the concept of the streaming systems we've discussed here backed up by a storage speed multiplier of 40x or 100x (depending on the console) opens the door to the kind of visual quality that exceeds the campaign being made possible in multiplayer. The streaming system also fits hand-in-glove with the fact that PlayStation 5 and Xbox Series X do not deliver what we would typically consider to be a generational leap in memory allocation. Modern Warfare 2019 also saw some tentative experimentation with ray tracing support, which may be invaluable research when dealing with the hardware RT functionality baked into the new consoles.

In the meantime, it's all about Season Four of Modern Warfare and the debut of a specific mode may put into practise a theoretical scenario I put forward to the developer: what if all of the battle royale players grouped together and one player stepped back to get all of the others into view - would the system be able to cope? According to the studio, they've witnessed legitimate scenarios where 50 to 100 players could be seen on-screen. Looking from one big city area to another via sniper scope, apparently up to 120 players could be observed. Season Four's new 50 vs 50 mode should really allow us to stress test the massively multiplayer aspect of this remarkable engine in a way that Ground War never could - and we'll be fascinated to see how it holds up.