In Theory: The Sony Gaikai Deal and What It Means for PlayStation

Digital Foundry's take on the marriage between console and the cloud.

Let's not get completely carried away by what today's news represents, because Sony's decision to acquire Gaikai does not mean the end of console gaming as we know it. PlayStation 4 is still going to be unveiled at next year's E3 and it will almost certainly be in our homes by the end of 2013. Whether we're talking console or cloud, the message is obvious enough though: Sony isn't putting all of its eggs in one basket.

What the deal represents is acceptance from a major console platform holder that gaming is fast approaching its own Netflix or iPod moment - the point where convenience and accessibility to content becomes more important than the inevitable hit to fidelity demanded by the underlying technology. We're not there yet, of course, but as Digital Foundry has discussed several times in the past, it's now a matter of when - not if - we will reach the point where the hit to quality ceases to become an issue for the majority of gamers.

While the overall level of the experience isn't there yet, even the first-gen cloud products offer some tantalising advantages which Sony would be keen to offers its customers:

- Playback hardware: virtually any device with an h.264 decoder chip can run Gaikai, encompassing tablets, smartphones, and Smart TVs. Even current-gen consoles could run cloud games. We've seen World of Warcraft streaming on an Xbox 360 via Gaikai and it looked great.

- No need for hardware upgrades: h.264 video compression is here to stay for many years to come, so you'll keep the same decoding devices and Sony will upgrade the Gaikai servers to accommodate the requirements of new games.

- No more updates, no more patching: this will be music to the ears of PS3 owners in particular. Lengthy firmware upgrades, patches - all of this is a thing of the past.

- Instant access: demos and games would not require lengthy downloads or installs.

"In a world where Instagram sells for $1bn, Sony's $380m acquisition of Gaikai looks like an astute piece of business that could potentially revolutionise its PlayStation business."

So when will cloud gaming be ready for showtime as a complete console replacement? The quality of the experience comes down to two specific factors: image integrity and control response. The former is going to require significant increases in bandwidth, because the current 5mbps level needs to rise to 10-15mbps to really solve the artifacting issues that are present in the first-gen cloud systems as they stand right now. But in a world where top-end UK internet connections have leapt from 2mbps to 100mbps in less than a decade, this is only a matter of time.

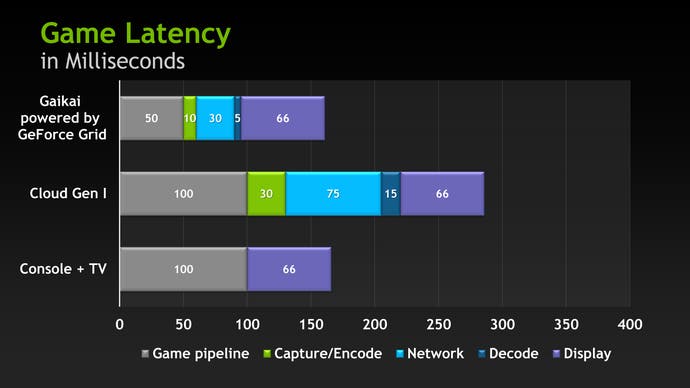

Response will also be improved by better infrastructure, but Gaikai deserves some plaudits for aggressively pursuing new server-side technology that shaves off precious milliseconds in the capture/encode/transmission process in the meantime. Even in its current form, Gaikai at its best attains isolated moments of performance magic that defy belief: this video shows Bulletstorm on the streaming service matching the input latency of the local Xbox 360 version, with Gaikai running on a basic ADSL connection around 40 miles away from the server. This measurement isn't consistent, there's a 'jumpiness' to the experience you don't get on the 360, and of all the games we've tested only Bulletstorm seems to be this responsive, but the fact we are seeing anything like this at all is a phenomenal achievement.

At $380m, it could be argued that Sony has secured something of a bargain. Gaikai not only has class-leading image quality for a cloud service, but it also has impressive coverage in both North America and especially Europe, with more localised infrastructure ensuring it commands a significant lead over arch rival OnLive in terms of the all-important latency issue.

Gaikai is also noteworthy in that it has created partnerships with key technology providers that should see its quality of service increase significantly going forward. The tie-up with NVIDIA for its GeForce GRID technology is an interesting case in point - image encoding occurs on the GPU, cutting down capture and encoding times significantly, and there are hints in the documentation that decoding time has also been improved too somehow. In the world of cloud technology, every millisecond saved is an enormously important achievement.

Cloud Meets Console: The First Steps

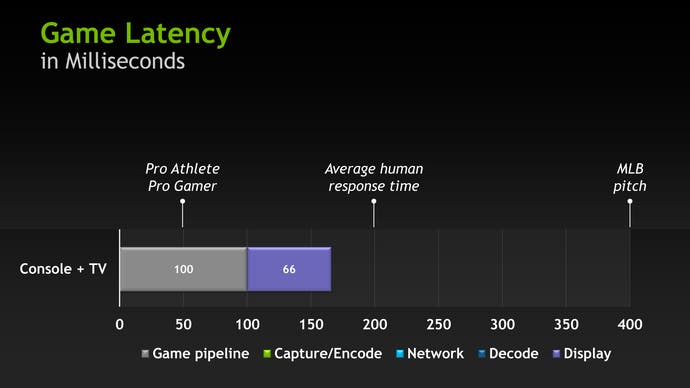

All of Gaikai's image quality and latency optimisation efforts have been built around PC technology, which in the short term may cause issues for Sony, because cloud servers aim to provide tolerable controller response by running games at twice the frame-rate of a typical console title. Local latency on a 30FPS game (defined by the time taken between button press and the resulting action on-screen) is around 100ms at best, typically dropping to 50-66ms when run at 60FPS. Gaikai and OnLive aim to use that latency "saving" to offset the cost of encoding, transmitting and decoding video. The result is streaming gameplay with ballpark console response levels - in theory, at least.

There's nothing to stop Sony simply installing a big bunch of PlayStation 3s in each datacentre, but the result would be highly sub-optimal as there would be no 60FPS vs. 30FPS latency off-setting at all - all the 'cloud stuff' would simply be added to the existing lag. Sony's Remote Play isn't particularly effective for this exact reason, and that's running on a local connection.

"Gaikai hasn't just sat back and waited for internet infrastructure improvements - its work with NVIDIA on GeForce GRID shows a determination to lower lag in all areas of the pipeline."

That being the case, it would be far better for Sony to make use of the infrastructure that's already there. The obvious first step would be to run a range of back-catalogue PlayStation titles on PC under emulation. Sony already runs PS1 and PSP titles completely under software on PS3 and Vita, while the firm is making big strides in running PS2 titles on PS3 through pure emulation. Gaikai datacentres would provide a lot more horsepower, and in theory we could perhaps see the same 60FPS vs. 30FPS latency offset in action. We discussed this in-depth a while back. While it's unlikely we'll actually see it, these games could also be rendered in HD resolutions too, just as current open-source PC emulators do.

Running PS3 titles in the cloud would be far trickier - for Sony's own games at least. Third-party publishers could simply deploy their existing PC versions of multi-platform titles on the Gaikai servers, but quite what the platform holder would do with its first-party titles - designed from the ground up for the PlayStation 3's unique hardware - is a difficult issue to address. Emulating the RSX GPU wouldn't be too challenging - at heart it is very similar to an NVIDIA GeForce 7950GT - but software emulation for the Cell Broadband Engine on current-gen PCs would be a huge technical achievement.

PlayStation 4 and the Cloud

The implications of this deal for next-generation PlayStation gaming are also challenging. Gaikai's datacentres are built around Intel CPUs and NVIDIA graphics cores, a situation that is not likely to change bearing in mind how closely the company is associated with these partners. PS4, on the other hand, is hotly rumoured to be using AMD parts for both CPU and GPU, perhaps even integrated into a single processor.

This leaves Sony with two different routes to bring PS4 games to the cloud: first, by creating its own datacentre-specific version of the hardware, or alternatively by generating two different versions of each game. The first approach may make more sense for Sony's first-party studios - they can continue to target the strengths of the fixed architecture and rely upon beefed-up datacentre PS4 hardware to provide the 60Hz upgrade they need to bridge the latency gap. The second approach may prove more favourable, however: third-party publishers already create PC versions of their games and adapting them to the Gaikai datacentre standard would be a reasonably low-effort procedure.

"Sony can't just place PS3s in the Gaikai datacentres - the lag would make for borderline unplayable gameplay in any kind of action game. Back-compat via PC emulation is the best route for catalogue titles."

Embracing the cloud as a cross-platform format does have some limitations, however - upstream bandwidth on home internet connections is typically very low so the inputs sent client-side would be limited. It's difficult to imagine that camera-based games will be able to stream their data up to the servers, for example (something Microsoft must be pondering bearing in mind its Kinect 2 plans). For Sony, this may require some thought about how it would handle any prospective motion control peripheral.

Not only that, but there's also the fact that native 60FPS games thrive on precision response - Street Fighter or Call of Duty, for example - simply won't play as well via the cloud, no matter how much infrastructure improves. Multiplayer games could also feature additional latency between players, and won't match the work netcode engineers have done with cutting-edge P2P experiences - like Uncharted 3's multiplayer mode, for example.

On the flipside, the nature of the platform does have some inherent advantages over and above the obvious fact that you wouldn't need to buy an expensive console, nor update firmwares/patch games. Cloud servers can locally host hundreds of gigabytes worth of data, and assuming SSD-style hardware, it could access that vast reserve of storage immediately, opening up a wealth of potential for bespoke online-only games. Secondly, cloud servers will almost certainly enjoy highly significant spec advantages over any home console - so the base visuals being encoded could potentially benefit from the likes of extended draw distances, higher-resolution textures etc.

What We Can Expect - And When

With the ink still drying on the documents, it's unlikely that we will see any major changes to Sony's existing console or PlayStation Network service offerings at any time in the immediate future, though current Gaikai demo streaming could be implemented pretty painlessly. Completing the acquisition won't happen overnight either, and coming up with the ways and means in which PlayStation software and datacentre servers can work together is also going to take time. Sony is also going to have to figure out how to handle Gaikai's existing licensees - it's hard to imagine that the company will have much of an interest in handling the cloud streaming services of HDTV rivals Samsung and LG. Suffice to say, it's early days and it's almost certain that the only reason we actually know about this acquisition at all is because of shareholder and regulatory obligations.

But Sony and Gaikai have time on their hands. In the UK at least, fibre-optic infrastructure rollout is proceeding apace and this represents the fundamental building block that could turn a cool piece of tech into a viable, PlayStation-quality experience. At the same time, we're almost certainly around 16 months away from the launch of Sony's next-gen console - time will be tight here but hopefully the R&D people will be able to work out how cloud and PS4 can work together in that time period. (Members of Sony's Advanced Technology Group and Sony Santa Monica were seemingly caught by surprise by the announcement this morning, if their tweets are taken at face value.)

"OnLive is being mooted as a Microsoft acquisition target but with valuations as high as $1.8bn, the Sony's Gaikai tie-up looks like even more of a bargain."

There's also a phenomenal opportunity for fundamental change here. In an era where many are beginning to doubt the sustainability of the £40/$60 boxed retail model, a shift to cloud gameplay could see the introduction of new pricing models: monthly subscriptions, game rentals, even "pay per minute" - Gaikai's current billing strategy for partners using its demo programme. Sony has been very progressive with its PlayStation Plus offering, but it's difficult to make the most of its current subscription offers when they are accompanied by multi-gigabyte downloads, lengthy installs and sometimes even patching. In these respects, Gaikai could change everything.

In the meantime, all eyes shift to Microsoft and how it might possibly respond. OnLive was targeted as a potential acquisition target in the recent "Xbox 720" leak, but despite being first out of the blocks, the service came up short in key, quantifiable aspects in a direct Face-Off with Gaikai. At the same time, with some analysts valuing Steve Perlman's outfit at an eye-watering $1.8bn, the Gaikai deal looks like the bargain of the century by comparison.