Dishonored is a game that improves with every play

A dish worth honouring.

Having decided to replay Dishonored recently, I was faced with a dilemma. Not a big Walking Dead "choose which of these people you want to live" dilemma. More of a Bioshock-level dilemma. In my excitement over going back to Arkane's magical murder-sim, I had neglected to consider that I am a parent now. As such, I am as likely to find time to return to a game I have already played as I am to find El Dorado in one of my daughter's nappies.

Then I had a brainwave. While I have played Dishonored several times, my partner has never experienced the dubious delights of Dunwall. A joint holiday to plague-town has been on the cards for, well, about four years. So I figured, rather than trying to find a spare 20 hours to replay it on my office PC, I'd pick up a copy of the PS4 version and we'd play it together over a few evenings. It was a perfect solution.

Or so I thought.

Whenever a game offers me the opportunity to be nice, I'll always take it, no matter how interesting the alternative path is. I always play Paragon in Mass Effect, or a goody-two-shoes Jedi in Knights of the Old Republic. With Dishonored it's non-lethal stealth all the way, blinking my way past checkpoints and patrols, with a smattering of tranq-darts and choking if the situation demands it. I'm not sure why I do this. I love violent action games when said violent action is the only way forward. But when I'm given the option, I'll choose sneaky bastard over stabby bastard every time.

My partner, as it turns out, plays Dishonored like a tornado with a grudge. Her escape from Coldridge prison was less Shawshank Redemption and more Shank-shank Detention. On her first mission to assassinate High Overseer Campbell, she killed 57 people. I didn't know there were fifty-seven people on that entire mission. She used the Rat Swarm power with the same frequency that most players use Blink. She thinks Granny Rags is nice.

For someone who does their utmost to ghost through Dishonored, watching my partner wreak havoc through Dunwall was like watching someone enjoy a work of art by setting it on fire. There were moments when I unconsciously began climbing up the back of the sofa in horror, which to be honest only encouraged her further. When the game introduced hackable rocket-turrets in the second mission, the slaughter went from extreme to positively industrial.

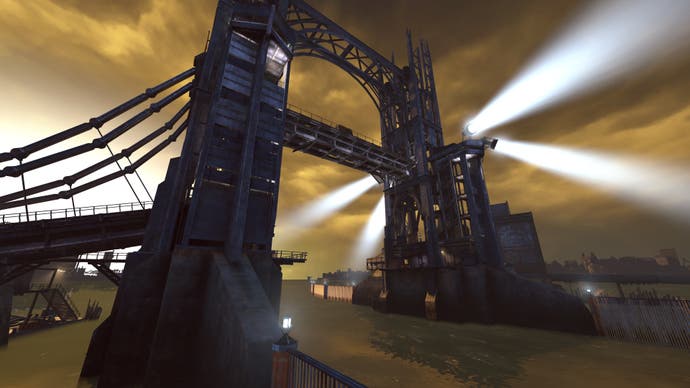

After a frenzied first couple of missions, however, something interesting began to happen. As we drifted beneath the sunset-soaked arches of Kaldwin's Bridge to kidnap natural philosopher Anton Sokolov, my partner began to explore the quieter side of Dishonored. She sneaked past guard-posts wherever possible, only bringing out the blades when an alarm sounded. She began exploring the environment the way she had previously explored Corvo's kill-animations, searching for ways past and around obstacles, instead of charging straight through them or obliterating them from a distance. Where I had always stuck to my stealthy ways, she embraced Dishonored in its totality.

I, meanwhile, was fascinated by how that initial onslaught had reshaped the playing field. Streets and houses I remembered as calm and orderly were now stricken with panic. Guards battled with weepers while terrified citizens danced in puddles of rat-teeth. As I watched, I recalled a long-running criticism of Dishonored that the chaos system punishes the player for experimenting with the game's tools. Frankly, I'm no longer sure that holds water.

If anything, the Chaos system makes a high-chaos playthrough more interesting. The world becomes livelier and more unpredictable as the systems wrestle control from the designers. The Lord Regent retreats to a safehouse on the roof of Dunwall Tower, making it far more challenging to reach him. The ending, while certainly darker, is in tune with the blood and death and sickness you've witnessed up to that point. In fact, the worst thing about High Chaos is, when transporting you to the final mission, Samuel the Boatman (aka the loveliest NPC in gaming) expresses his disappointment in your violent approach. "You seem to have gone out of your way to be brutal." Oh Sam! Don't let a mountain of corpses come between us. I can change!

Witnessing Dishonored through the lens of another person revealed so much else about the game too. For example, while my partner sliced her way through dozens of lowly guardsmen, she preferred many of the non-lethal options for dealing with the targets themselves. She merrily branded High Overseer Campbell a heretic. She wavered over sending the Pendleton brothers to their own slave-mines, before deciding they probably deserved it. She refused to pack Lady Boyle off to a lifetime of imprisonment with her creepy, obsessive "lover". We deliberated each of these decisions together, and it highlighted how superbly thought-out those dastardly nonlethal alternatives are. In a recent interview with PC Gamer, co-director Harvey Smith describes the Lady Boyle alternative as "regrettably dark". Personally, I think having a nonlethal option that has many players conclude death to be preferable is remarkable design.

Being away from the controls allowed me to absorb more of the world too. One of the biggest criticisms of Dishonored on release was that it's story was poorly told. While I'm inclined to agree that some of the characters, such as Emily, Admiral Havelock and the sneering, aloof Outsider, aren't sufficiently fleshed out, I think there was some confusion between poor storytelling and a straightforward plot.

Dishonored's story isn't so much about Corvo or Emily, or even the broader conspiracy to unseat the Lord Regent, as it is Dunwall itself. The tale of this city in decline is told not through the beats of the storyline, it's infused in the architecture around you. It's written on the signs and advertisements plastered across the crumbling brick walls. It's gleaned from snippets of conversations muttered by on-duty guards and prowling street-thugs. When you sneak your way through the deprivation of the slums to attend the party at Lady Boyle's manor, with its lavish banquet, extravagant décor and elegantly outfitted guests, words aren't needed to convey the rapacious inequality that the Lord Regent's rule sits precariously atop.

I even noticed entirely new things about the game, tiny details such as how whiskey bottles (carried by bottle-street thugs) explode when shot, or that Overseers will whistle to their dogs if they spot you. I've experienced the game three times now, and each playthrough reveals something different, systems and behaviours I've never witnessed before. In the Flooded District, my partner crept up on an assassin perched on a rooftop and choked him unconscious. It was neatly done, but she forgot to hoist him onto Corvo's shoulder. The assassin toppled forward over the roof edge, and landed with a wince-inducing crunch in the street below. Oops. As we recovered from laughing at this grisly slapstick moment, a swarm of rats appeared and set upon the corpse, just to compound the indignity of his demise.

When Dishonored launched four years ago, much of the conversation around it was dominated by comparisons, how it borrowed aesthetically from Half Life 2, how it embraced the immersive spirit of games like Thief and Deus Ex, how it saw Arkane hitting it big after showing such promise in Arx Fatalis and Dark Messiah. It was viewed as a wickedly clever merger of other games, and while it received a lot of deserved praise for that, I also think the individuality of Dishonored got a little lost. The focus was on the components of the machine rather than how seamlessly they fit together.

Returning to it recently, the only game I thought about was the one in front of me. I've mined out the guts of so many open worlds, exhausted the procedural algorithms of games like Minecraft and No Man's Sky. But my enjoyment of Dishonored, my appreciation of it, only increases each time I encounter it. The sandboxes may be smaller, but they're exquisitely constructed, and the mechanisms within so delicate and intricate, that what results is a game that is simultaneously timeless and ever-changing. It's a game that renews itself each time you play, not through some procedural algorithm, but through pure human craft. My partner is already traversing Dunwall again, attempting a non-lethal playthrough this time, and I don't find that at all surprising.