Distant Worlds: Universe review

Go flight.

The universe is big. Really, really big. Unfathomably big. So big that our brains cannot understand the numbers involved. Back in 2006, I remember being really excited about Spore and Mass Effect. Both were games that promised they'd really give us a sense of scale; tiny people, tiny beings, competing on a mind-bogglingly large stage. They failed, of course - and for the longest time I felt that I'd never see something that would really make me feel utterly insignificant. And then I played Distant Worlds.

Distant Worlds is both defined and limited by its bigness. On the one hand, its sheer size gives it a radical and unique feel; on the other, it struggles with scale in the same way we do, and can't effectively handle its own dizzying complexity.

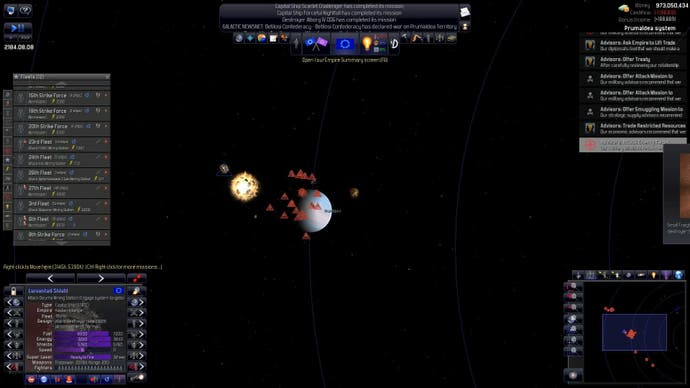

Distant Worlds puts you at the helm of a civilization. After choosing an era of galactic history, you'll guide your race, helping them develop warp drives and then move out into the stars. And there are a lot of stars. An average map will have a few hundred, each with its own set of planets and most planets with their own set of moons. Each of those can carry bases, colonies and mining centres. Even so, you can build many of those same structures near massive nebulae, or near other cosmic phenomena. Even a small map is mind-bogglingly dense. Seriously, here's a picture:

In just about every solar system lurks some ancient ruin or long-lost secret. I recall encountering countless structures that each seemed to point somewhere else. With small, procedurally generated details, Distant Worlds establishes both a temporal and a spatial sense of scale. Knowing that other star-faring civilizations came before you and that more will surely come after imparts a disturbing, morbid spin on the whole experience.

Much like other "4X" strategy games, Distant Worlds pushes you to explore, expand, exploit and exterminate the races and civilizations around you... kind of. Unlike even Civilization, a game often praised for its variety of non-military, non-action win conditions, Distant Worlds has a system that encourages growth of the private economy and far-reaching control. Each race also has its own specific victory condition. These are intended to reflect the intrinsic sensibilities of your populace, such as a predisposition for research or being the player with the fewest breaches of trade treaties.

Running around murdering everyone is still an option, of course. The game's default goal is having a third of the private economy, a third of the galactic population and a third of all colonies; technically, killing everyone that's not with you can achieve that, but it's not an explicit goal, just an implicit means to attaining another goal. And that's indicative of most of the game.

Really dense, complex strategy titles have a tendency to have very clear goals. Ostensibly there may be many ways to achieve those goals, but they tend to require a lot of micromanagement to push an empire smoothly in one direction or another. Distant Worlds isn't so discrete, though. It's not a monolith so much as an amorphous blob of code - for better and for worse.

For example: you're supposed to foster a general level of prosperity, but that also only applies to the private sector of the economy - something over which you have no direct control. As a leader, you can build starbases, maintain defensive structures and order the construction of mines and escort trade ships, but you can't do much beyond that to influence economic success. Building up the private economy is one step removed from the tools you actually have at your disposal, and this is another trait that feeds into the bigness of Distant Worlds.

Much like real-world economies, a few simple policy changes won't immediately fix a fundamental systemic problem. In Civilization, budget deficits can be solved with a few clicks, but in Distant Worlds it can be a lengthy affair. You'll likely need to increase tax revenue, which means building more starbases and mining facilities, but those also cost a decent chunk of resources to complete and maintain. Chances are that you'll be running low on some critical resource like lead or gold as well, and that you'll need to keep your empire limping along until you can find an untapped planet that has what you need. Too often, economic troubles are abstracted so far out from their root cause their true solution isn't imminently clear - in both games and in the real world. Distant Worlds does a phenomenal job of representing that.

Those layers of depth are hidden, initially at least, and with good reason. With such intricacy comes the necessity to learn... a lot. Typically I can pick up a new strategy game in just a few minutes; most have an underlying sensibility that guides their interface and their rule set. Distant Worlds isn't one of those games. I had to spend a few hours and a few practice games with some cheats turned on before I really started getting the hang of it.

That said, the game definitely tries to help players out. Besides a few basic tutorial missions, Distant Worlds keeps most of its layers automated until a player is confident enough to start taking that piece into their own hands. That's a great thing too, because there's a lot here. Beyond the ship and colony management, there's also construction, diplomacy, character management, tax rates, ship designs, smuggling missions and more. To new players it would be beyond overwhelming, and for many even the automation won't help enough.

When everything does finally get working and all of these little elements come together, play can be exceptionally rewarding. Perhaps my most memorable experience involved stumbling across an ancient capital ship that needed to be repaired. My advisors said they thought it might be powerful enough to destroy whole planets with one shot. So - while Star Wars was playing in the background, purely by coincidence - I set my construction ships to work, building the technological terror back up piece by piece.

It took a few dozen years' worth of in-game time, but eventually I had managed to revive the beast and soon began a reign of terror that continued for at least five hours. Quite unlike the original Death Star, my "planet destroyer" was capable of zipping around the galaxy at ludicrous speeds. No waiting to move past a planet here - I'd just aim and fire. It didn't take long for me to dominate galactic affairs. If any empire dared cancel a trade agreement, I'd warp in, destroy their home planet and be on my way.

This was amazing to me, mostly because the ship was an extra. An add-on. I could have missed it and still won. It didn't sit at the end of a tech tree, it wasn't a natural or reasonable monstrosity to have. I just got there first. That's far from my only story, too. As I've said, this is a game that is built for scale. No matter how thorough you are, there's probably someone who got somewhere first. There's probably someone that unlocked a secret that you'll never know.

There's a lot more that I could say about Distant Worlds. I want to talk how play expands in several distinct stages, each remarkably different from one another and ultimately pulling off the Spore concept far more effectively than Maxis itself did. I also want to talk about the curious lack of Marxism as a governing style, and the metaphorical weight of it all. But really, Distant Worlds will succeed or fail for you on one criteria alone: are you someone that has the time and patience to handle a game that is almost incomprehensible?

For fans of older 4X strategy titles, trying Distant Worlds will be a given, but for all of its amazing scale, the game largely doesn't help you manage it. The automation is great for new players, but when that's turned off you'll be faced with staggeringly large spreadsheets and a positively ridiculous amount of data. So much happens in the background that, even on a high-end machine, this graphically bland game chugs more often than you would expect. While Distant Worlds may be a paragon of its style, I can only recommend it to a select few: those with beefy computers and plenty of time to really dig into the meat of this stunningly elegant and impressively wide-ranging bit of software.