Does bad archaeology make for the best games?

X never marks the spot.

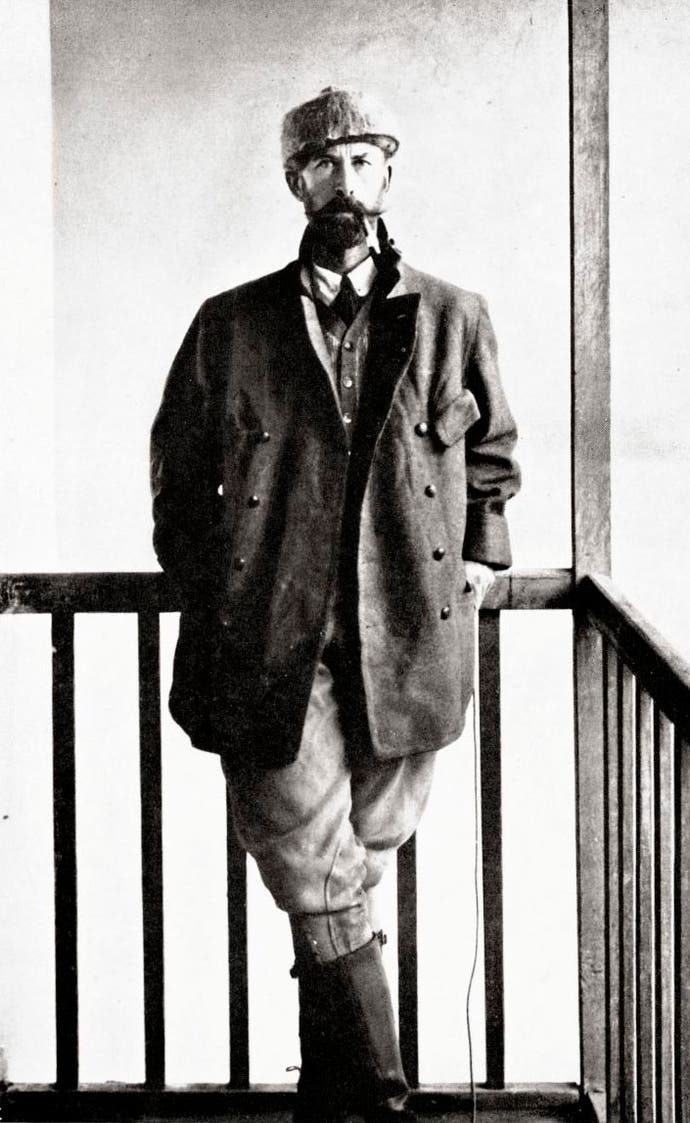

In 1925 the British explorer Percy Fawcett and his expedition team set off from the Brazilian city of Cuiabá in search of the Lost City of Z, which Fawcett was sure lay hidden in the depths of the Amazon rainforest. It was the culmination of years of obsession for Fawcett, who had come to believe in the existence of an advanced lost civilisation based on sketchy travellers' tales and a mysterious idol given to him some years earlier by the pulp author H. Rider Haggard and said to be from the region.

Abandoned cities had been found in jungles before, of course. It was still not that long since 19th-century expeditions had mapped the Maya city of Tikal in Guatemala (though knowledge of that, like many 'lost cities' had never been entirely lost to the indigenous population). But Fawcett's quest for Z was no conventional archaeological enterprise. Fawcett had long been a devotee of spiritualism and the esoteric, and his obsession with Z was deeply intertwined with his beliefs about human history. He had determined the origins of Rider Haggard's idol by showing it to a psychic, who had performed a reading and told him that it had been saved by a priest from a temple in a land that was sinking beneath the waves. In Fawcett's mind Z wasn't just an indigenous city that had been swallowed by the jungle and had fallen out of memory, it was a relic connected to Atlantean civilisation, the key to a deeper understanding of the esoteric mysteries that preoccupied him.

There's only one way this story could end, of course. Fawcett's expedition set off into the jungle and were never seen or heard from again. Numerous follow-up expeditions have found no trace of them or their lost city.

Fawcett's doomed expedition reads like something out of Lovecraft or Machen. It sounds like an Indiana Jones film. It sounds like a game plot. In fact, Fawcett was probably one of the inspirations behind Conan Doyle's The Lost World and its hidden Amazonian plateau full of dinosaurs. Combine that with Fawcett's American contemporary Hiram Bingham III, discoverer of Machu Picchu and the lost Peruvian city of Vilcabamba and you have all the key elements of the first Tomb Raider. You could slot Lara or Nathan Drake or any of gaming's archaeologist heroes into Fawcett's story and the only thing you'd have to change is the utter failure at the end.

Fawcett isn't unique here: almost all popular stories about archaeology are built on the model of people like him. Not archaeologists but pseudo-archaeologists; not rigorous academics but two-fisted, buccaneering adventurers with at least one foot in the occult and a maverick disdain for scientific process and conventional wisdom.

I've been an archaeologist for fifteen years now. I've never found a lost city; the closest I've ever come to occult artefacts were exhibitions of objects from the Society for Psychical Research's archives held in Cambridge University Library, and of John Dee's magical paraphernalia at the British Library. The only Nazis I tend to encounter are on Twitter. As far as I can tell, other archaeologists' experiences are broadly similar. I did work with an archaeologist called Lara on my first dig, but she went unarmed and literally didn't kill anything at all the whole time I knew her.

OK, fair enough. Real archaeologists are nothing like Indiana Jones. Tomb Raider and Uncharted aren't an accurate depiction of good academic practice. I'll wait a moment while you get over your shock. But these kind of stories have an effect. Recent surveys have shown that more than 50 per cent of Americans believe in lost precursor civilisations, despite a total lack of supporting evidence (I've written about precursor civilisations before). With fringe theories, both fictional and ostensibly non-fictional (in the case of shows like Ancient Aliens or the books of Erich von Däniken and his successors) being the dominant way archaeology is represented, their outlandish claims are gradually normalised. People without specialist training and access to the data become less able to tell where the boundaries lie between fact and fiction. I can attest to this personally: I remember at school arguing with a classmate who had watched a Graham Hancock documentary the night before and refused to believe that its spurious claims of a lost ancient precursor civilisation being responsible for the existence of pyramids in disparate parts of the world could be anything other than true, because otherwise why would Channel 4 have broadcast it?

But isn't this just a matter of storytelling, no different from all the science fiction adventures that play fast and loose with the laws of physics to tell a good yarn? If you're watching Star Wars and complaining because there's sound in space or because the ships move like planes then surely you're missing the point? There's an element of truth in this - these are good stories. I didn't need to spend so long on the Fawcett at the beginning of this article, but I did because he's interesting. Like many archaeologists I watch and love Indiana Jones, I've played and enjoyed Tomb Raider and Uncharted, and so on. And yet there is a difference. A couple of them, actually.

Firstly, there is science fiction out there with a broadly realistic approach to science, if that's what you're after. 'Hard science fiction' is a thing, even in mainstream media: The Expanse has received a great deal of praise for its relatively grounded approach to science and how it uses it to open up new storytelling possibilities. Star Wars or Doctor Who aren't the only flavour of science fiction on the menu. This is much less the case with history and archaeology, especially in video games. You can pick up a historical novel, often rich in well-researched period detail, but how many historical games are there without any element of the supernatural? Among major franchises the closest I can think of is Assassin's Creed, where the esoteric elements briefly punctuate otherwise fairly grounded narratives, rather than being pervasive. The lack of fantasy elements in an RPG was sufficiently unusual that Kingdom Come: Deliverance made them one of its key selling points. There are a great many strategy games, of course, but they often lack pre-defined narratives; often (but not always) their historical settings are little more than window-dressing for otherwise fairly standard wargaming mechanics. Probably because of its origins in things like Dungeons and Dragons and computer science, science fiction and fantasy are gaming's equivalent of a side order of fries. They come with everything, by default.

But it's not just that alternative (or rather, non-alternative) views of archaeology and the past are thin on the ground; it's that archaeology and history matter to people in ways that physics or other sciences don't. Sure, we all rely on gravity in a thousand little ways every day, but very few of us build our identities around it. History, on the other hand, is intimately bound up with questions of who we are and where we came from. It belongs to people. When you play fast and loose with history, it matters for the modern communities whose identities and claims to legitimacy are bound up in that history.

It might seem harmless to claim that aliens or Atlanteans built this monument or that lost city, but in doing so, you're taking those achievements away from the people who actually accomplished them. Often those people are the ancestors of modern indigenous communities which have suffered colonialist oppression and marginalisation. And this brings us to pseudoarchaeology's troubling relationship with race.

When Fawcett searched for an advanced lost city in the Amazon, he believed it had to be connected with Atlantis and populated by whites because he couldn't conceive that the indigenous population would be capable of the kinds of wonders he imagined. Likewise, he believed the Toltecs of Mexico must be 'delicately featured, of a light copper colour, blue-eyed, probably with auburn hair... To the degenerate autochthones the Toltecs were superior beings.' Erich von Däniken, elder statesman of the ancient aliens hypothesis, has wondered in one of his books, 'Was the black race a failure and did the extraterrestrials change the genetic code by gene surgery and then programme a white or yellow race?' More recently, the fringe theory known as the Solutrean hypothesis, which suggests that America was originally settled by Europeans before the arrival of Native American populations, has been seized upon by white supremacists in an attempt to delegitimise indigenous populations and their right to the land. Many pseudoarchaeological theories are rooted in ideas of superior and inferior races and the implicit or explicit assumption that non-white societies couldn't have accomplished great things without help.

Pseudoarchaeology makes for good stories. I'm not trying to deny that. As a dedicated fan of sci-fi and fantasy, I can't help feeling that everything benefits from a little sprinkling of the unreal, whether that be a trip to the shops or an epic video game. But we also have to be careful that these aren't the only stories we are telling, to think through their implications and be mindful of who we might be casting in our lot with. Aiming for 'historical authenticity' (whatever that is) doesn't automatically free us of these potential problems, as the recent controversy over Kingdom Come: Deliverance has shown, but now that gaming is enjoyed by people well beyond its traditional roots in a male-dominated geek culture founded on fantasy, science fiction and wargaming, it's probably time we broadened our palates and stopped having fries with everything.

Further Reading

David S. Anderson 2017 - ''Obsession and Longing: How the Lost City of Z was created to be forever lost'. ArqueoWeb 18, 130-144. (He's also a good follow on Twitter if you want more of this sort of thing).