Dota 2 review

Definitely MOBA.

It's the summer of 2010. Typing to a backdrop of Chatroulette and Chilean Miners, it becomes clear that none of us in the Rock, Paper, Shotgun staff chatroom, where I worked at the time, know how to react to the news that Valve, a company famous for giving gamers what they want before they know they want it, is making the sequel to Defense of the Ancients.

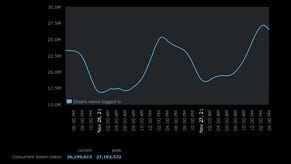

Today, Valve's characteristic accuracy is intact. Dota 2's beta is the most popular game on Steam, boasting a peak of 329,977 simultaneous players. This falls far short of League of Legends, Dota 2's biggest competitor, which was able to boast five million concurrent players earlier in the year, but this month the real race starts. Valve is rolling out access to Dota 2 in successive waves, and while Dota 2 is arriving late, it's doing so with an inarguably more generous free-to-play business model, which only charges for cosmetic upgrades.

Yet for the growing shadow that Dota 2 casts, it remains intimidating, or even bizarre to all of us looking in. Which isn't unfair. Dota 2 is bizarre. It's a game where a cockney porcupine can work together with a god of destruction and a ghost to try to temporarily kill a particularly high-level tree.

But Dota 2 represents something far larger than the sum of its endless, mismatched parts. Let me put this as simply as possible:

While everyone was trying to make a Multiplayer Online Battle Arena game - a MOBA - Valve went off and purchased a sport.

You're probably aware of the basics of the MOBA genre at the very least. Two teams of players fight in one large arena, with several lanes connecting their two bases. The game you play is to fight alongside the droves of NPC troops that your base produces, levelling up your hero, knocking down sequential defensive enemy towers, until finally your team smashes their way into the other team's fortress-like base in a dramatic end to the match.

"The second-to-second gameplay is, secretly, as pure and beautiful as the game is convoluted."

Next, the thing to know about Dota 2 is its comedic scale. It currently offers 102 unique, playable heroes from the original Dota's roster of 112, and with matches frequently lasting 35 minutes (though occasionally stretching past an hour), you're looking at more time than you ever spent in Skyrim just to try them all. Every hero has different stats and four unique skills, but can also be equipped with any one of almost 130 items.

Developing a familiarity with all of these different components might take 200 hours. To know how to combine them instinctively, you're looking at 400 hours.

Which isn't quite the mortifying challenge it sounds like. Yes, by the end of your first six months of Dota 2 you'll have skimmed an amount of knowledge from the surface of the game comparable to six months at university, but you'll have had fun doing it. This isn't Dwarf Fortress. While you'll want to know everything, it's possible to play knowing nothing, and if you're playing with friends - the biggest factor in successfully trying Dota 2 - you'll have a great time learning. If you're interested, the diary I previously wrote for Eurogamer is the story of five friends learning Dota 2 together. There's magic in those early days.

These extremes are what everyone knows about Dota 2 - how it involves this many hours, this many items, how its millions of players are capable of intense cruelty when you don't know something they take for granted. But it's a huge shame this is the main takeaway, because the second-to-second gameplay is, secretly, as pure and beautiful as the game is convoluted. It's an incredibly tense, precise and uniquely emotional game of positioning that draws easy comparisons to fencing or dancing.

At the simplest level, you're trying to glom as much experience and gold from the battlefield and inflict as much damage as possible, without ever overextending yourself. You want to be one step ahead of anyone in your lane, charging them just before they choose to retreat, or falling back the instant they realise the terrain favours them.

On a larger scale, you're silently coordinating with your entire team at all times. By far the easiest way to get a kill is to pounce on outnumbered opponents, which means your team has to lock into a pack mentality. This can be as simple as making sure to attack and run away together, or as complex as goading an enemy hero into your territory by being low on health and doing a half-assed job of retreating, coaxing them deeper, deeper, as your friend circles round behind them.

This is the beautiful game, the supreme form of the MOBA which everyone else working in the genre is trying to capture like lightning in a bottle. Slipped in among all of Dota 2's thousand lessons about which pairings of heroes make a heartbreakingly tough lane, or where to place Observer Wards (and when they should be Sentry Wards, and whether that's even your job) is a more tender, emotional core than I've ever seen in a multiplayer game. You might have played 500 hours of Dota 2, but you might still suck because you can't resist a kill when it's in front of you. Because you get sloppy when you start losing, or winning. Because you can't predict your friends.

This is where comparisons between Dota 2 and organised sport come from. It withstands discussions of tactics, depth and teamwork better than anything I've ever played. The purpose of the game's library of heroes, items and skills isn't simply giddy maximalism. It's what Dota 2 offers as a substitute for physical fitness; instead of a growing mastery your real-life body, Dota 2 offers a growing mastery of a range of powers, combinations and even abbreviations so absurd that a common feature when my friends and I first started Dota 2 was having to stop and reflect on the absolute nonsense we were saying. To stop and catch yourself moving the pub's salt and pepper shakers and squeezy tomato to illustrate tri-laning to your friends.

Once you're in, Dota 2 is so entertaining, and subverts so much of the perceived wisdom of game design as to be troubling. No commercial studio could have made a game this demanding, with matches this long, that fused genres like this, or included such counterintuitive tactics as killing your own soldiers. So what does it say about our industry that it's the most popular game on Steam?

The original Dota mod was a fascinating curio. Viewed from this angle, of course Valve had to own it. The only strange part remains, with every publisher under the sun now trying to scratch together their own MOBA, how everyone let them get away with it.

Whatever - the series is undoubtedly better off with Valve as the curator of the brand. This is a gorgeous update, with every hero a colourful character, with a thoughtful, powerful, continually evolving UI, and a business model so nice, so kind, so smiling and unselfish as to be properly insidious. Following the Team Fortress 2 model, Dota 2 is entirely free. Better yet, after completing a match people will randomly win loot from the game's bulging catalogue of cosmetic weapons, clothes and hats for specific heroes.

The moment you're OK with the idea of spending money, the second Dota 2's won you over and your eyes begin traveling towards your debit card, you're spoiled for choice as to what to buy first. A £1.59 key for one of your locked chests, the Dota 2 equivalent of scratchcards? Full sets of clothing for your favourite hero? New announcers, from the narrator of Bastion to Half-Life's own Dr. Kleiner? New skins for your wards, couriers, even your HUD?

Most of this stuff is made by the community via the Steam Workshop service, meaning a cut of your pay goes straight to the artist, as well as making Dota 2 seem that much more organic and alive.

A more recent example of Valve's mystic knack for letting community and commerce spill over is in The International 2013, Dota 2's most prestigious tournament, which takes place next month. Currently advertised front and centre in the game's menu is a £5.99 Interactive Compendium, a bundle offering in-engine access to the matches, live items drops while you're watching, an opportunity to predict winners, one-of-a-kind taunt items, animations and more, with all purchases of The Compendium adding to a Kickstarter-like bar increasing the cash prize of the tournament and unlocking further uses for the Compendium.

Valve has shown slightly less interest in the Herculean task of making Dota 2 remotely accessible, but progress is being made. Dota 2's scalable bots have always been genuinely entertaining to fight against (if not with), and they were recently bolstered by a suite of tutorials that Valve is growing into a larger New Player Experience. The game's robust matchmaking was, just a few weeks ago, joined by a new system for banning that Valve say caused a "35% drop in negative communication interactions". I think that means fewer players are being pricks.

Overall, Dota 2 is a monumental piece of craftsmanship. Valve has managed to transport Dota's house-of-cards design into a new engine, infuse it with life and colour, and attach a business model that people don't simply accept, but enjoy. This is a grand update.

But it's still an update rather than a sequel, which means Dota 2's biggest flaw - a dirty stretch of genes it has passed on to almost all other MOBAs - is very much present. Losing a match of Dota 2 is often irredeemably, structurally unpleasant.

MOBAs lock players into a panicked race to level up their characters fastest. This brings about a tension which powers the entire game. It's why a kill is a beautiful or stomach-wrenching thing, depending on which side of the ambush you're on. But it also means that when another team is better than you, the game begins handing them advantages. Which is exactly as much fun as it sounds like.

Games are still trying to absorb the success of Dark Souls at the minute, which taught us that having something to lose isn't an intrinsically bad thing. But this is a whole other level. The comparison would only work if dying in Dark Souls transported you to a purgatory where five beefy dudes proceeded to bounce you off the walls for 25 minutes.

Not that this is something any MOBA community on earth would change. It's part of the culture. Who could ever willingly pave over those stories of legendary comebacks? But I've played enough Dota 2 to have had my share of bad evenings, where you and your friends go online and just lose. Nights full of possibility compacted into dismal scoreboards and exhausted Skype conversations. In these lost lunch-hours and unlucky weekends, closing the Dota 2 client can feel less like you're playing a game and more like you've just gotten your fix.

"There's never been a better time to get involved than right now, with the New Player Experience and influx of fresh blood.

All of which makes Dota 2 an absurd video game to try to recommend. Being the largest and most immediately open MOBA, with Valve showcasing its talent for rewarding and fostering a community, it demands and offers more than literally any game I can think of. It's almost more comparable to basketball than most commercial games. Something utterly opaque bearing no endgame, but that could happily fill every waking second of your life.

Instead, I'll just say that if any of what I've described has sparked your interest, you owe it to yourself to set the client downloading and take a look. The business model of Dota 2 makes it the best MOBA option out there, and there's never been a better time to get involved than right now, with the New Player Experience and influx of fresh blood.

Just remember to spend your starting cash, and make sure someone buys the courier. Oh, and when Riki starts showing up in your games, just get some Sentry Wards down and don't run away. Also, you always want a Bottle when in mid-lane, and runes spawn at 0:00 and again every two minutes. Practice last-hitting before you go online. And if you're jungling, memorise where the low-level Creeps are.

Actually, you know what? Forget all that. Just have fun.