Dragon Quest 8: Journey of the Cursed King retrospective

Once upon a Slime.

Fairy tales, like so much fiction, are all about leaving the village. Figuratively, of course, as the young man or woman departs the familiar confines of childhood and strikes out into the wilds of puberty, with its rioting hormones and hair-sproutings. But literally too, with many an acne'd protagonist peeling back the village gate in order to make their way in the terrible world, so full of life, love and painful lessons. The Japanese RPG is no different in this regard. Wake up from a start screen in a wispy hamlet or pastoral town and you can be sure you'll be kicked into the wildernesses before the hour's gone. This is how the digital hero's journey goes.

As such, by the time of Dragon Quest 8's release in 2005, we were experts at leaving villages. You got a village that needs leaving? Just leave it to us. Better yet: leave it with us, especially if you're at all handy with a broadsword or know a gutsy magical spell or two. Because if leaving all those villages has taught us one thing, it's that the first thing you'll face on the other side of the gate is a whole lot of fighty trouble. That's the other thing fairy tales are all about: the loss of innocence at the hand of experience (and experience points), the struggling traversal from zero to hero, the fistfights with swamp rats.

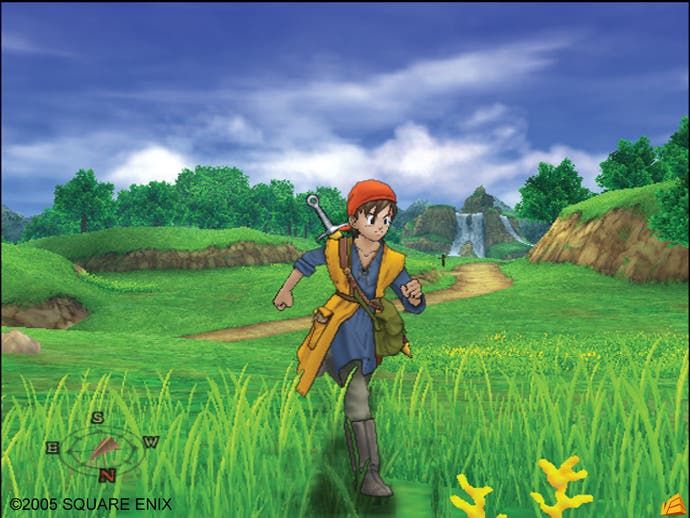

Even so, leaving Dragon Quest 8's opening village (the sun-baiting town of Farebury, to be precise) was quite unlike any departure yet experienced. Before Level 5's game, stepping out of the village into the wide world was more usually a case of stepping out of the village into a world map, an abstraction that allowed players to cross miles of terrain in a few short hops across a piece of on-screen parchment before diving into the next location. In Dragon Quest 8 there was no abstraction: you leave the town gates and step into a world fully formed and fully revealed.

Pick out the grey crinkle of stonework on the side of some mountain in the distance and, with some blistering effort and the odd fighty interruption, you could trek there, cross-country. Finally, the world-map divide that your suspension of disbelief could never quite bridge was gone, and the video game fairy-tale took a long step towards Tolkien-esque literalism, where every trip is rendered in explicit detail. In prose or on film this kind of descriptive thoroughness can prove stodgy, slowing the story and overwhelming the reader or viewer. But in video game, the opportunity to investigate each thicket and knock on every house door creates immersion, not just a sense of geography but, importantly, of your place within the geography.

This is doubly important in a story boasting a mute protagonist, who can neither comment on the surroundings nor provide insight or context for all that you're seeing. In ex-manga columnist Yuji Horii's epic the bandana-topped protagonist says nothing, his name and (unless you manage to access the extended ending) identity a silent secret. The world has to do much of the talking.

Not that Dragon Quest 8 is a game lacking in other voices. Every Japanese video game to leave its country must be made twice over. There's the original work, executed by the developer and led by the creative vision-holder. Then there's the work of the localization team, whose job it is to translate the text and, if they're attentive and skilled, preserve the humour and transport the cultural references from one nation to the next.

Dragon Quest 8 marked a new era for Japanese RPGs, which had for decades suffered from unsympathetic, impoverished translations. Here, instead of the usual batch of American-drawl Z-list game voice actors we were presented with a vibrant range of European idiolects: the cockney Yangus, the prune-y, upper class King Trode and a great many others. The performances have the sort of eager exuberance typical of local theatre rep. but set against the competition of the time, they feel like Shakespeare. Not only this, but the script is carefully transported into English with care to retain the fine notes of comedy and tragedy while the synthesised soundtrack of the Japanese version was re-recorded with an orchestra, providing an unbroken chain of melody and intonation to back the exploration.

The result of this convergence of stimuli is a live-in fairy tale. This has always been the full extent of Dragon Quest's ambition, where its competitors have perhaps harboured loftier dreams. Horii is a light storyteller, never happier than when threading simple but affecting yarns. In the case of this game, he chooses a tightknit and likeable questing group to drive the story forward. The mute, unnamed protagonist, the stubbled East-ender Yangus, the buxom Jessica (whose 'Sex Appeal' skills can be developed to immobilise enemies in a tumescent stupor) and Angelo - stay together over the course of the adventure, forming the natural bond that comes through shared experience. They travel with their ultimate quest objects: King Trode and his beautiful daughter, Medea, both of whom have fallen foul of a wicked spell that has turned the former into a triple-chinned troll and the latter into a horse.

This Grimm-like premise placed Dragon Quest 8 on a different branch of the Japanese RPG tradition to other titles of the time, one largely eschewed by rival developers who had left stories of knights, princesses and evil spells in favour of more 'serious' plots and settings. For developer Level 5 it represented its type of own village departure, leaving the confines of the company's own game world, Dark Cloud, to embark on a new journey, taking other peoples' stories and interpreting them in their own high contrast, vivid style. In this way Dragon Quest 8 begat Ni no Kuni, the company's collaboration with the master Japanese fairy tale tellers, Studio Ghibli - and Level 5's hero's journey was complete.