Dream a little bigger: the legacy of Mike Singleton

How an unassuming English teacher from Cheshire expanded the boundaries of gaming.

In their infancy, games were small. Mostly this was due to necessity. Early computers lacked the memory and processor power to store lots of information or handle multiple inputs, so the pioneering developers tended to stick with what worked: single screens and simple movements.

There were several who kicked at the fences, however, and forced their groaning hardware to accommodate ever larger ideas. Of those ingenious few, Mike Singleton stands out for the sheer scale of his ambition. Singleton died last week, succumbing to cancer at the age of 61. He leaves behind not just a catalogue of classic games, but a legacy of innovation and ambition that continues to inspire developers and gamers alike even today. If you've enjoyed an epic open world role-playing adventure in recent years, from Skyrim to Fallout, from Dragon Age to Fable, you've benefited from Singleton's prodigious imagination.

Back in the early 1980s, however, Singleton was an English teacher at Mill Lane High School, in Ellesmere Port, just north of Chester. Intrigued by the new microcomputers that were creeping into classrooms and homes, he began creating games in his spare time. Sending his efforts to Clive Sinclair, he was invited to create a game for the ZX-81.

Even on a machine with a scant 16k of memory and almost no capacity for graphics, Singleton was already thinking big. Rather than one game, he came up with 50, packaged together as the self-explanatory GamesPack1 compilation. Such generosity led to healthy sales, and Singleton was able to leave the classroom behind and become a full-time games designer.

Quickly graduating to the ZX Spectrum, Singleton turned out a series of arcade games for obscure publisher Postern. Though games like Shadowfax and Siege didn't exactly stretch the hardware, they did feature wizards riding majestic horses and brave souls defending a besieged keep from evil orcs, neatly hinting at one of Singleton's biggest influences: Tolkien's Lord of the Rings.

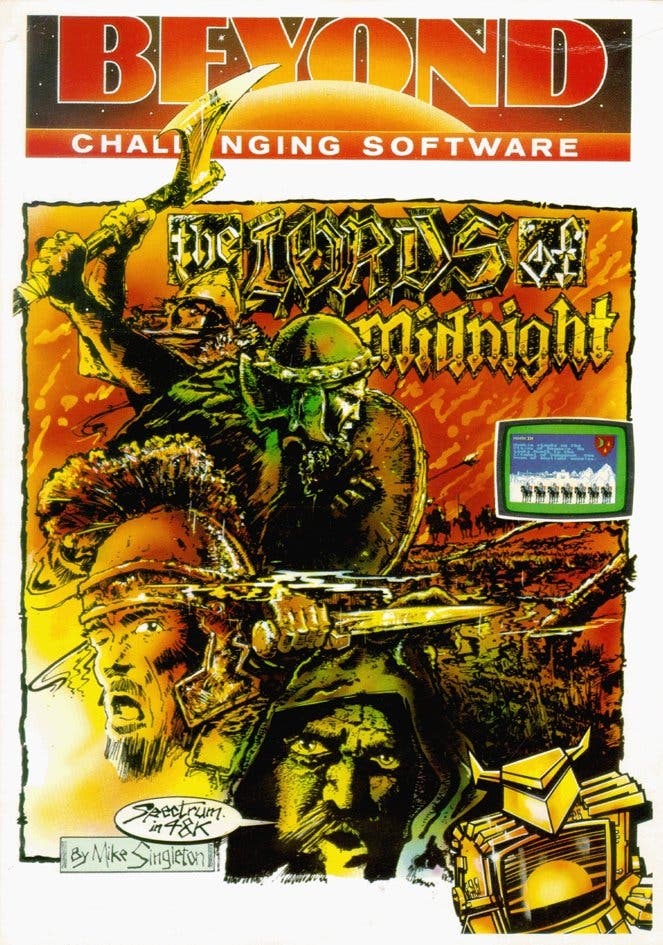

It was an influence that would take centre stage for his next game, and perhaps his first masterpiece. When Lords of Midnight debuted in 1984 the gaming canvas had been broadened from the single-screen days of old, but it was still far from expansive. At most, games boasted of having a hundred locations, which were often virtually indistinguishable screens. Lords of Midnight, in contrast, had 4000. Not only that, but it conjured up a rudimentary first-person game world where the player could stand in one spot and rotate around, viewing a panoramic - and consistent - landscape from eight directions. These weren't randomly generated lines made to look like mountains, but actual places that could be revisited and approached from different angles.

It wasn't just the size of the map that put other games in the shade. Lords of Midnight innovated in gameplay too, with multiple playable characters and a layered approach to victory. Starting with four lords and tasked with defeating the evil Doomdark, the player was free to roam the land, discovering enchanted weapons and items, recruiting new characters to their cause and taking part in a genre-bending saga that had the scope as well as the aesthetic of Tolkien's beloved novels.

In 1984 Lords of Midnight was an absolute revelation. Outside of space-faring classic Elite, nobody was making games on this scale, with this much freedom. Even the official text adventure based on The Hobbit condensed Middle-earth into a compact handful of screens. Contrasted with the flip-screen platformers and truncated adventures that were the 8-bit norm, Singleton's game looked like it had been beamed in from some exotic future where games unfurled in widescreen wonder.

Singleton continued to evolve the themes and ideas of Lords of Midnight in a sequel, Doomdark's Revenge. There were now 48,000 different views in the game, and 100 characters. Five rival factions could be battled or recruited. No wonder that Singleton's name was becoming a selling point in itself. "Another epic adventure from the marvellous imagination of Mike Singleton!" screamed the cassette inlay.

The late 80s were a turbulent time, however. In 1986, Beyond Software, the publisher of Lords of Midnight and Doomdark's Revenge, announced it had signed a deal with Paramount to create the first Star Trek game, and Singleton was asked to turn his talent for vast worlds and flexible gameplay to the adventures of Kirk and Spock. What sounded like a dream assignment became a protracted farce as the game's release date slipped further and further away. What happened behind the scenes has never been revealed, though the grapevine hummed with word that Paramount's inflexible approach to approvals kept it tied up while pixels were shaved from Spock's ears and other cosmetic tweaks were made and remade.

Development on Star Trek overlapped with that of Singleton's own Dark Sceptre, and as the months passed, the press began to express doubts that they would ever see the light of day. As these were now the only games in development at Beyond, rumours began to spread that the company was on the verge of collapse. Star Trek eventually limped out on Atari ST, to reasonably positive reviews, but it's clear where Singleton's passion lay.

Released in 1987, Dark Sceptre was more strategy game than adventure, with an impressive array of orders you could give to your varied troops. You could bribe or challenge. Insult or bewitch. Charm, harass, persuade or threaten. You could even order them to avoid certain characters, or to simply roam the map autonomously.

Where Lords of Midnight and Doomdark's Revenge unfolded through thousands of static screens, Dark Sceptre put the player in the thick of the action, as gigantic sprites, half a screen high, stalked through the side-scrolling gameworld to fulfil your commands. It's still one of the most visually impressive Spectrum games, and one that backs up its visual allure with serious depth.

Dark Sceptre arrived at the peak of the 8-bit computer era, but the industry was changing. As one of the few truly marketable names in game design, Singleton was in demand from increasingly corporate publishers.

Melbourne House, the publisher which had put out The Hobbit text adventure, hired Singleton to work on War in Middle-earth, an officially licensed strategy game based on Tolkien's work. It should have been the perfect match of creator and content, yet the game fell short of expectations. It wasn't so much that Singleton wasn't up to the task, more that his credibility stemmed from games that surprised and enchanted by unfolding in unpredictable ways. Tethered to the unchangeable prose of Tolkien's novels, War in Middle-earth struggled to offer the same replay value. Clearly, Singleton and licensed properties were not a good match.

As the 8-bit era clumsily passed the baton to the 16-bit computers, the prospect of even wider technological boundaries to push against seemed to invigorate Singleton. His 1989 opus, Midwinter, still stands as one of the all-time great works of game design, as astonishing for Amiga gamers as Lords of Midnight was for Speccy owners.

Although dark fantasy had given way to snow-blasted espionage, Midwinter revisited many of themes from Lords of Midnight and Doomdark's Revenge. It was open-ended, with a single gameplay goal built around the defeat of an overpowering foe and complete freedom to approach that goal in any way you saw fit. The concept of recruiting additional characters also recurred.

Far from suggesting a one-track creative mind, what Singleton did over his career was the exact opposite of what most developers end up doing. Normally, a developer hits on a popular gameplay mechanic and then finds as many ways to reuse it as possible. Singleton worked the other way around. He had big, bold concepts - freedom of choice, character interaction - and then kept coming up with new mechanics to explore those ideas.

Midwinter, and its sequel Flames of Freedom, sadly proved to be the last big hits that Mike Singleton would produce. He went on to develop sci-fi strategy game Starlord in 1993, and worked on a game adaptation of Wagner's Ring Cycle for Psygnosis. He even returned to Lords of Midnight with the fully 3D real-time semi-sequel The Citadel, but mainstream acclaim eluded him as console and PC games began to rely more on large teams and less on the singular visions that had flourished in the 1980s.

In the new millenium, Singleton kept working in the industry, though his contributions were now swallowed up in larger projects. LucasArts' action game Indiana Jones and the Emperor's Tomb, arcade spin-off Gauntlet: Seven Sorrows and even Codemasters' Race Driver: Grid all benefited from Singleton's input, even if the player at home was unaware of it.

That his death came just as the industry was going through another seismic shift, throwing the balance of power back in the direction of small indie developers and iconoclastic designers is a tragic irony. Never a developer who dwelt on the past, and who saw each new hardware generation as a wonderful challenge rather than a step away from retro purity, we'll never know what he could have done had he been able to really sink his teeth into iOS or other emerging platforms.

At the time of his death he was working on a remake of Lords of Midnight for the iPhone, and while a straight up remake doesn't really seem like Singleton's style, it's the knowledge that it was more of a rehearsal for starting development on the long-awaited third entry in the Midnight trilogy - The Eye of the Moon - that stings the most. That Singleton kept coding right up until his death - he posted this "remastered" version of his 1983 game Snake Pit just weeks before he died - is both an inspiration and a sad promise that will now remain unfulfilled.

Unassuming and humble to the last, Singleton never grabbed the celebrity limelight as enthusiastically as some of his peers, nor did he give many interviews or feature in the sewing circle of industry gossip. Once the home computer era ended, taking with it the heyday of the solo programmer, he simply retreated to the background and kept on working.

Yet what he leaves behind is more than just a body of work. It's a manifesto; a monument to the idea that digital boundaries are there to be shattered. When others were building rooms, he was building worlds. When others built worlds, he built universes. While gaming's frontiers would have been pushed back sooner or later, few could have done it as confidently and successfully. The fact that Mike Singleton was one of the first to chart interactive territory we now take for granted means we all owe him a huge debt.